“…Let China sleep, for when she wakes, the World shall tremble…” – Napoleon Bonaparte

This quotation by the French emperor regarding the great bastion of the orient, is one of the most famous in history. It’s simply said, simply understood, and simply true. China has awoken in the 21st century, and the world trembles from the impact of what it has done, and what it continues to do.

In the 21st Century, China is one of the fastest-growing countries on earth. It has one of the largest populations, it has a skyrocketing middle-class, an educated youth, and a gigantic manufacturing industry, producing everything from radios to TVs, fridges, to those annoying little bobble-head things that people use to adorn their desks and the dashboards of their automobiles.

China’s growth and change has not only been large, but also fast. It’s the end-result of over a century of political and cultural turmoil, of wars, revolutions, more wars, more revolutions and still more wars and revolutions. This posting will look at how various events in Chinese history gave us the China we have today.

Taming the Dragon – The Opening of China

China. Zhong Guo. The ‘Central Kingdom‘. Land of wonder, mysteries, ancient traditions, fascinating culture, marvelous inventions…and fried rice.

For centuries, China was intensely isolationist. Its very name in Chinese, ‘Zhong Guo‘, means the ‘Central Kingdom’, or ‘Central Country’. In the eyes of the Chinese, the world revolved around China and China was the center of it. China not only had enormous land and wealth, but an enormous population, and at one time, the largest seagoing navy in the entire world.

The Chinese mastered such arts as the manufacturing of paper and gunpowder. They created the first seismographs, they invented wheelbarrows, the compass, porcelain, silk, astronomical clocks, and repeating crossbows, as quick to fire as any bolt-, or lever-action rifle, provided the magazine was full. Its claim to being the ‘Central Kingdom’ seemed well-founded.

Despite all these technologies, discoveries, advancements and skills, China remained closed to the world. The Qing Dynasty, the first dynasty which most Westerners were likely to have made contact with, and the last dynasty of Imperial China, upheld a strict policy of national isolationism. ‘Barbarian‘ Westerners are not allowed into China, and they are not allowed to trade with China. And China is not interested in anything outside of its own borders. And if it is interested, it is only to improve China’s lot, and not to improve that of any other nation.

One example of this extreme isolationism is the trade of silk.

Europeans loved silk. It’s soft, it’s smooth, it’s light, it breathes, and it comes in so many pretty colours!

But they had no idea what it was, how it was made, or where it came from! They could purchase it, they could trade for it, but they could not see how it was made. This was because the manufacture of silk was a state secret in Imperial China. Sharing this knowledge with outsiders, especially WHITE outsiders, was punishable by death! China relied on its silk-monopoly to keep the Westerners begging for more, and to keep foreign money coming into the Empire.

Westerners were desperate to trade with China, but China did not want to trade with the West. It saw no need to trade with the west. The West had wooden bowls and plates, or plates made of brass or copper or pewter or clay. The Chinese had pure white porcelain!

The Westerners had cotton and wool, weaving-looms and spinning-wheels. The Chinese had soft silks and satins, spun from the cocoons of silk-worms. They saw no need for Western fabrics!

Everything the West tried to ply the Chinese with, the Chinese turned up their noses at. But the West never gave up. And in the mid-1700s, the first cracks in old Imperial China began to appear.

The Canton System (1757-1844)

The persistence of the West to trade with China finally culminated in the creation of the ‘Canton System’, in the 1750s. Under the ‘Canton System’, Western ships (mostly British and American) could trade with the Chinese, in China.

But only at one port. And at one port only.

Canton, in southern China.

And in Canton, only out of certain buildings. And with certain merchants.

This stifling arrangement was China’s way of controlling Western activity in China, and of preventing the Westerners from bringing their filthy, barbarian ways into the serenity of the Central Kingdom. And the Westerners had better be damn grateful for it! The Chinese were letting them into their glorious Central Kingdom! Previously, this had not been allowed – During the 1600s, Western ships wishing to trade with the Chinese were confined to doing so on the island of Macau. But when this proved unsatisfactory to the British and other Western nations, the Canton System was developed.

A ship docking in Canton from a country in the West (such as the United States), could purchase wares from one of thirteen warehouses or ‘factories’. Certain merchants in Canton were given permission by the Chinese government to trade with the West. These merchants, called ‘Hongs’ (‘Profession‘ in Chinese), set themselves up near Canton Harbour, establishing warehouses, shops and places of business to do trade with the growing number of Western ships which visited Canton each year. Each factory or ‘Hong’ catered to a specific nationality. So the British would have one Hong, the Americans would have another, the French or Spanish might use another Hong, and so on. All thirteen hongs or traders operated under the ‘Cohong’. The Cohong was like the guild or trade-union, that supervised and regulated the trade conducted by the Thirteen Factories. And up until the First Opium War of the early 1840s, they held a monopoly on all trade in the Canton System.

The Port of Canton, in 1820. Flags, L-R: Denmark, Spain, U.S.A., Sweden, Great Britain, and Holland. The warehouses and buildings fronting onto the port held the goods which foreign sailors wished to purchase from the Chinese

The Canton System and trading with the merchants under the control of the Cohong was a stifling arrangement at best. But for the Western powers, it was an even more frustrating arrangement because of one thing.

Silver.

The Chinese insisted on only trading in silver. Not gold. Silver. And only silver. The problem with this was that the Western powers didn’t have any silver! Or at least, not enough to sustain trade with China. Western powers held stores of wealth in gold! Silver was used for pocket-change, teapots, trays, candleholders and cutlery. Not for buying silk!

The Chinese insistence on silver was a huge strain for the Western powers, especially Britain, which loved Chinese tea and porcelain. Struggling to find an answer, they stopped trading using silver, and switched to something else – Opium. This was going to be a disaster.

The Opium Wars (1839-1842 & 1856-1860)

Starting in the late 1700s, the British started trading in Canton using opium. Small amounts at first, but gradually, they grew. Opium was easily accessible to the British – they shipped it in from India and Bengal, and a suitable alternative to paying for Chinese goods using silver (of which the British government was rapidly running out). The Chinese government was extremely critical of this corruption of their people, and made several diplomatic attempts to stop the opium-trade. Letters and laws were written and passed, inspectors and enforcers were appointed to arrest Chinese drug-dealers, to seize shipments of opium and to have them destroyed, and to try and prevent the spread of the drug which was rapidly poisoning the health of China.

The Opium Wars (especially the first one) was not just a war on drugs, however. And there were other factors involved. Most of them linked to trade and foreign relations.

It had been the desire of the British to establish diplomatic relations with China, as far back as the 1700s. Something that the Chinese refused to do. Partially because the British wanted to set up a British Embassy in Peking. Peking being the Imperial City, was of course, off-limits to foreign barbarians! The Chinese refused, and the British were forced to postpone their dreams for proper diplomatic relations with China for another day.

If there were no proper diplomatic relations, how did all these trade-agreements, such as the Canton System, come about?

The Chinese believed that their emperor was the Son of Heaven, appointed by God to rule on earth as his representative, under the Mandate of Heaven. A similar concept in Western society is the Divine Right of Kings. The only difference is that, as a king is divinely appointed, he cannot be questioned, and his actions cannot be questioned. The actions of an emperor could be questioned, however. If an emperor’s reign was marred by disasters and misfortune, this was seen as his having lost the Mandate of Heaven (the blessing of God, basically), and that he should step down and let someone else take the reins of power.

Being that the emperor was the Son of Heaven, all other national leaders were therefore seen as subjects or tributaries of the Chinese Emperor. This included all foreign heads of state.

You can imagine how well that went over at Windsor Castle, or the White House.

A foreign government paid China a tribute. In return, the Chinese government gave a reward for this tribute, and allowed foreign powers the privilege of trading with China, as a tributary state. Foreign powers put up with this because the riches they could get from China were considered to be worth the expense. But it was a stifling system at the best of times. And when issues sprang up regarding payment and trade using silver and opium, an already uncomfortable situation got even more tense.

Starting in the 1780s and 90s, the British started smuggling opium into China. This was technically illegal, but it didn’t stop them – they did not have enough silver to trade with the Chinese, and the trade was too good to stop, simply because they didn’t have the right kind of metal! They had to find something else which the Chinese would accept as payment for their precious commodities, and opium was it.

The Chinese government fought back with opium bans, and the situation deteriorated rapidly from there. By 1839, despite trying to placate British merchants, and Chinese officials and sailors boarding British ships and destroying their shipments of opium, and everything else that had happened, China and Britain went to war.

The first Opium War (1839-1842) was what finally cracked the nut of China open. Suffering humiliating losses and defeats at the hands of the British, in 1842, the Chinese government sued for peace. There’s more about the Opium Wars in another one of my posts.

The Treaty of Nanking

The First Opium War was a key event in Chinese history, and in producing the China that we have today. Without the opium war, China would never have opened its borders. And without that, it would never have been exposed to Western science, technologies and ways of thinking, which would produce effects on China that shaped it into the nation it is today.

But first, there is the Treaty of Nanking.

The Treaty of Nanking is what finished the First Opium War, in 1842. It was signed on the H.M.S. Cornwallis, anchored in the Yangtze River, off of the ancient city of Nanking, giving the treaty its name. It was the first of the “Unequal Treaties” which the Chinese were forced to sign. Called ‘Unequal’ because by the terms of the treaty, China was expected to allow the British to do certain things in China, but the British had no obligations to do anything in return for China. The Treaty mostly dealt with issues of trade, foreign relations and foreign movement within China. Specifically…

– The Canton System of the Hongs and the 13 Factories is Abolished.

– The British will continue to trade at Canton. In addition, four other port-cities will be opened for trade. These were Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, and the most famous one of all…Shanghai.

– The British expected to be paid reparations for the war, as well as reparations for all the opium they had lost before the war. In total, a sum of $21,000,000!

– Until all reparations are paid (over a period of three years), British troops will be stationed in China. As more reparations are paid, the number of troops will accordingly decrease.

– All British P.O.Ws would be released at once. All Chinese collaborators with the British would be given a pardon by the Chinese government.

– The island of Hong Kong will be given to the British, for the purposes of establishing a British Colony.

The conditions of the Treaty of Nanking directly contributed to many changes in China which can still be felt and seen, even today, over 150 years later. Thanks to the Treaty, Shanghai is the largest city in China. Thanks to the treaty, Hong Kong became a British colony, and thanks to the Treaty, China was finally opened to outside influences and ideas.

The International Settlement of Shanghai (ca. 1842/3-1943/9)

These new ideas and influences, methods of government, styles of dress, western architecture, education and technology entered China through the Treaty Ports. The ports of Canton (Guangzhou today), Amoy (Xiamen today), Foochow (Fuzhou today), Ningpo (Ningbo today), and Shanghai were opened up to provide the British with avenues with which to trade with China. The most famous treaty port was Shanghai.

The original city of Shanghai was a small, walled settlement built on the bank of the Huangpu River, a tributary of the mighty Yangtze. The British established a foreign concession-zone to the north of the city, to the southern bank of Suzhou Creek. This was in 1843.

It was in this zone that the British conducted the business of trade. It was originally meant to be a purely business settlement, but as merchants and traders and businessmen arrived, so did their families. And their friends. And their friends’ families. And their friends and families met and mingled, and married, and created more families. And all these people wanted the comforts of Old Blighty. They wanted churches, houses, schools, shops, and everything else that a city like London or Paris might have. So the British Concession spread from being a purely business zone into being a town in its own right.

Soon after the British, the Americans showed up in 1844. They established a zone on the north bank of the Suzhou Creek. The French arrived in 1848, establishing a zone to the south of the British concession, and to the west of the original walled city. Over time, the British and American zones expanded and grew along the banks of the creek, and spread north and west and east along the bank of the Huangpu River.

Deciding that it was silly for each country to have its own zone, in 1863, three years after the end of the Second Opium War, the British and Americans unified their respective settlements in Shanghai, creating the famous International Settlement of Shanghai. The International Settlement of Shanghai (referred to simply as ‘The Settlement’ by most people) became an island of Westerners in the middle of China, and by far the largest and most famous of all Western expatriate zones in China. This was due to a number of reasons:

Shanghai was located close to the mouth of the Yangtze, the most important river in China.

As the ‘Gateway City’ to China’s interior, Shanghai received a lot of river-traffic. And this meant that more merchants stopped in Shanghai than almost any other city in China, apart perhaps, from Peking.

The residents of Shanghai (who creatively called themselves ‘Shanghailanders‘), enjoyed immunity from Chinese laws. As Western expats, they could not be prosecuted by the Chinese legal-system. This was another condition extracted from the Chinese by the British after another unequal treaty, after the second Opium War (another condition was the right to send Christian missionaries deep into the Chinese interior. This would have disastrous consequences, which I’ll mention later).

The Bund, International Settlement of Shanghai, China, 1928. Looking North. On the right is the Huangpu River. Across the road and to the west, beyond the line of buildings, the British Concession of the Settlement

The International Settlement was called the Whore of the Orient. The Paris of the East, and many other things besides, reflecting its growing reputation as a city of loose morals, drugs, gambling, prostitution, gangland violence, high-society living, jazz-bands, nightclubs, betting and racing, and of course, being a passage through which opium could continue to be shipped to China. The firm of Jardine, Matheson & Co, an import-export business (still around today), shipped all kinds of things into, and out of China. Most of its money was made through the opium-trade. They had their headquarters on the famous ‘Bund’, the waterfront promenade that ran along the shore of the Huangpu River. Also located on the Bund, and established there in 1865, was the Shanghai office of a small company called the Hong Kong-Shanghai Banking Corporation. At the same time in Hong Kong, another office of the same company was established. Today, it’s called H.S.B.C.

The Legation Quarter of Peking (1861-1959)

While the International Settlement of Shanghai was the most famous of the Western expat-zones in China, the Legation Quarter of Peking was also high on the list of importance.

At the end of the Second Opium War in 1860, the victorious foreign powers extracted yet another humiliating treaty from the Chinese. Called the Treaties of Tientsin (Tianjin today), they allowed the foreign powers to establish legations in Peking, they allowed for foreign ships to navigate the Yangtze River, the opening of even more treaty-ports, and the right for no restriction of travel through China, of all foreigners.

These conditions were all kicks to the crotch for the Chinese. Especially the establishment of foreign legations in Peking! As the Imperial City, Peking, the capital of China, was reserved for the Emperor, the Empress and the Imperial Court! It was the location of the famous Forbidden City! How DARE the Barbarians insist that they could establish a concession-zone there! But the Chinese could do nothing to fight back.

Legation Street, within the Peking Legation Quarter

The Legation Quarter was a collection of houses, shops, buildings and foreign legations, which housed foreign diplomats, their families, diplomatic staff, and western expats living in Peking. The Quarter only made up a small area of Peking, but it was small in the same way a needle in your ass is small. You’ll never forget that it’s there.

The Boxer Rebellion and the Siege of the Legations (1900)

The Boxer Rebellion, culminating in the famous Siege of the Legations in 1900, was another major event in Chinese history that led to its current position in the world. This is covered in greater detail in another one of my posts.

Infuriated and insulted by European (mostly French, but also American) Christian missionaries invading Chinese villages and destroying their ancient belief-systems, an extremely anti-Western organisation which was dubbed ‘The Boxers’ by the Western press, started attacking, killing and laying waste to anything Western and Christian. This eventually led to the famous Siege of the Legation Quarter, an almost two-month long assault on the Legation Quarter in Peking.

Messages smuggled out of the Quarter, fortified against the Chinese, made it to Tientsin, the nearest major city, and port, to Peking. Relief-efforts were organised and the Eight Nation Alliance (Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Japan, the United States, Austria-Hungary and Italy) sent troops to Peking to lift the siege.

The Siege of the Legations traumatised the West and the East. It showcased the weaknesses and inabilities of the Qing Government, it showed the military weakness of China, it infuriated the Western powers, and hastened the collapse of the Qing Dynasty, already on its last legs. It fanned the flames of Chinese republicanism, and made the foreigners in China feel extremely unsafe. But it did not have the desired effect of removing them from China’s shores. Instead, one of the responses was to build protective walls and gates around the entire Legation Quarter, to safeguard against potential future attacks, as well as to house soldiers within the compound!

China at the Turn of the 20th Century

By the year 1901, China is a country in turmoil. It has lost war after war, it has had to sign humiliating treaties that do nothing to improve its lot, the Qing Government is trampling all efforts to modernise and improve China, and on the 1st of July, 1898, one of the most famous events in Chinese and British history takes place – the British sign a 99-year lease with China, allowing them to take possession of the island of Hong Kong and the surrounding land of Kowloon, until the 1st of July, 1997 – the date of the famous Handover of Hong Kong.

As much as China struggled to resist change, it was being dragged, kicking, screaming and spewing obscenities, into the dawn of the 20th century.

The First Chinese Revolution (1911)

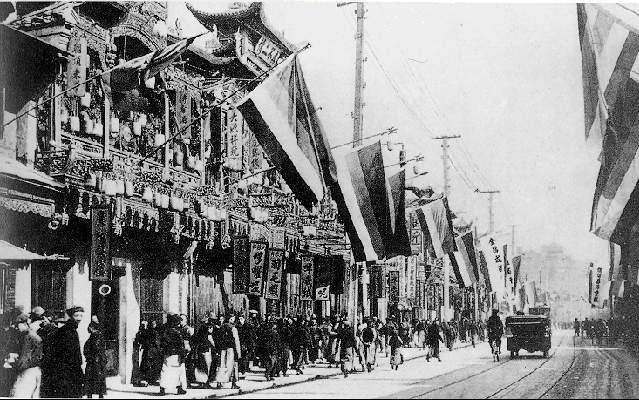

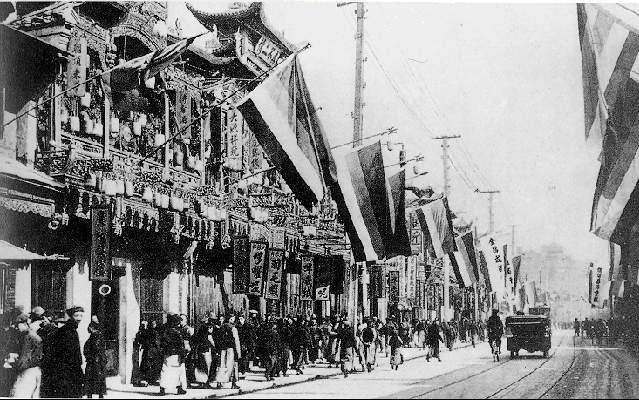

Nanking Road, International Settlement, Shanghai. Ca. December, 1911. “Five Races Unity” flags hang from the buildings of Shanghai, celebrating the success of the Shanghai Uprising

Humiliated and weakened by defeat after defeat, the Qing Government was on its last legs in the early 20th century. The First Opium War, the Taiping Rebellion, the Second Opium War, the Sino-French War, the First Sino-Japanese War and the Boxer Rebellion all served to showcase its weaknesses in protecting the people of China, and seriously challenging its assertion as the legitimate ruler of China.

The Sino-Japanese War of 1894 was especially humiliating – losing against a fellow Asian nation! Japan, a modern, Western-influenced Asian empire with an up-to-date army and navy, swept the Chinese out of the Korean Peninsula in a matter of six months and in the space of a year, Korea went from being a Chinese vassal state to being a colony of the Japanese Empire. A status it would hold until 1945, when the Second World War ended.

These continual defeats and the inability and corruption of the Qing dynasty caused many Chinese to lose all trust in their government. And in 1911, the ‘Xinhai Revolution’ took place, finally removing the Qing, a pseudo-Chinese Manchurian dynasty to begin with, from power.

The removal of the Qing from power was seen as the only way for China to improve its lot on the world stage. Chinese citizens, exposed to new ideas and modes of thought and governance, were furious that their own government was so completely impotent. The Qing government blocked reforms, attempts at modernisation, attempts at bringing Western technologies to China, upgrading the Chinese armed forces for the 20th century, and its continual failure to ward off foreign aggression or to do anything significant about the opium-trade.

These many grievances finally came to a head, and on the 10th of October, 1911, the revolution started with the Wuchang Uprising.

China, a vast country with many provinces and important cities, all located many miles from each other, was seen as the ideal place to build railroads by many of the Western powers. These railroads, linking the various cities and ports of China, were all privately owned and operated. To pay back the Western powers for the damage done during the Boxer Rebellion, the Qing Government wanted to put the railways under state-control. This infuriated many of the Chinese investors in these privately-run railroads. They’d lose millions! The Qing Government tried to pay compensation, but investors were unsatisfied. Riots and protests broke out, which culminated in the start of the Xinhai Revolution. This final misjudged move by the Qing court was the last straw.

The Revolution ended on the 12th of February, 1912 with the abdication of the last Qing Emperor, Puyi. The revolutionary government, the new Republic of China, was initially friendly towards Puyi. The emperor was very young (he ascended the throne in 1908, aged just three!), and was just six years old when he lost his throne! He had reigned for barely three years.

The Flag of China from 1912-1928. “Five Races – One Union“. Each race or ethnicity of China is represented by one colour on the flag

Initially, the government drew up the “Articles of Favourable Treatment” for the Emperor. Among these, included the conditions that…

…the Emperor could hold his title for life, but was not the ruler of China.

…He would be accorded all courtesies given to a FOREIGN head-of-state.

…For the foreseeable future, he could continue to live in the Forbidden City, but must agree to move to the Summer Palace once the new government had been fully established.

…He would receive a government subsidy of $4,000,000 Chinese dollars a year.

…The Emperor and his property will be protected by the State.

…and one which must’ve made men all around China very happy – the Court could not employ any more eunuchs!

The Emperor of China was devastated by the news of his dethronement. It became almost his lifelong ambition (at least, until the 1950s) to regain his throne, something which never happened. Or at least, not for very long.

Most people have probably heard of Lady Jane Grey, the “Nine Day Queen” of England, successor to Edward VI, who was son to Henry VIII. But how many people know of the 12-day Emperor? In 1917, Puyi was, for a very brief period, Emperor of China again, when one of the Chinese warlords restored him to power. However, this move was so extremely unpopular that before the end of two weeks, Puyi was once more forced to abdicate!

The Republic of China (1911-1949)

After the fall of the Manchu ‘Qing’ Dynasty, the Forbidden City was turned into the Palace Museum…which it still is, today. EVERYTHING inside the Museum was bookmarked and cataloged – even unfinished meals! And for the first time in hundreds of years, the Forbidden City and the Imperial Palace was opened to the general public.

The Republic of China, established by Dr. SUN Yat-Sen, would rule China from now on! Or so everyone hoped.

Dr. Sun was the first president of the Republic of China, and the founding father of the Republic. But much like the Weimar Republic in Germany around roughly the same time, the Nationalist Chinese Party, the Kuomintang (modern Chinese: ‘Guo-min-dang‘) and the Republic of China, were built on shaky foundations.

The KMT had an impossible task ahead of it. They wanted to modernise China, shake off the conservatism and restrictions of the Qing Dynasty and bring China into the 20th Century. They wanted medicine, electricity, railroads, telephones, radio and motor-cars. They wanted to be like the great democracies of the West, like the United States and Great Britain, where Dr. Sun had grown up, and had lived as a young man. There, he studied, lived and even became fluent in the English Language.

But they were fighting against centuries of entrenched traditions and superstitions. And getting people to change was very difficult. The ancient custom of binding womens’ feet had to be stopped, but enforcing the new foot-binding ban was difficult. Similarly was the change to get Chinese men to remove the humiliating, stereotypical long ponytails or ‘Cues’, which they had been forced to grow, and wear for centuries, under the rule of the Qing Dynasty. China’s intellectuals and politicians might’ve wanted a modern nation, but they would have to fight long and hard to get it.

The Warlord Period (1916-1928)

China is a HUGE bloody country. It’s bigger than the United States. And for centuries, one of the biggest challenges facing the rulers of China was…HOW do you rule, HOW do you govern, HOW do you control a population in a country that is THIS GIGANTIC!?

In an age before most of China had railroad, telephones, telegraph and radio, communications and the enforcement of law and the recognition of the new nationalist government was extremely difficult. As a result, the country fell under the grip of the Warlords.

The collapse of the Qing Dynasty caused a huge power-struggle within China, between the new Nationalist Government and the Warlords.

The Warlords were men who controlled the rural provinces of China (and there are several of them), using private armies. Between them, the Warlords and their respective armies controlled Sichuan, Shanxi, Guandong, Qinghai, Ningxia, Guangxi, Gansu, Yunnan, and Xinjiang provinces, encompassing much of the Chinese coast and the eastern and central parts of the country. By comparison, while the Nationalists theoretically governed all of China, their actual power was limited to the large population-centers, such as Canton, Shanghai, Nanking, Tientsin and Peking.

China in the Interwar Period (1919-1939)

China in the first half of the 20th century was rocked by conflict. In 1922, the Kuomintang and the newly-formed (1921) Communist Party of China joined forces in the “First United Front”, to tackle the issue of the Chinese Warlords. And while this was successful, the defeat of the warlords (in 1928) had only removed one problem from China, which was swiftly replaced by another – The Chinese Civil War.

In the foreign enclaves of China, such as the Legation Quarter, the International Settlement, and the other such quarters in Nanking, Tientsin and so-forth, Westerners took little notice of outside events. They still enjoyed extraterritoriality (damn, that’s a long word…) and were exempt from Chinese prosecution. The treaties signed with China in the 19th century were still in-effect, and within the foreign expat-zones, life went on as normal, even though, away from the bright lights of Nanking Road or the elegance of the Peking Legation Quarter, China was tearing itself apart.

The Nanking Decade (1927-1937)

In 1927, the decision was made to move the capital of China. From now on, Nanking would be the capital city, not Peking. But in actuality, Peking and Nanking had been chopping and changing as the capital city of China for centuries. In fact, their very names reflect this. “Beijing” just means “Northern Capital“. “Nanjing” just means “Southern Capital“. The official move was made in 1928, and Beijing was renamed Beiping, or “Peiping” (‘Northern Peace‘).

This move of the capital started what was called the “Nanking Decade”; the ten-year period when Nanking was the capital of China, and when, it seemed, for once, China was just…China. But the glitz of Shanghai and the calm of Peking, the bustling ports of Canton, Amoy and Tientsin were all a facade. Because in 1927, more than just the capital city was changed in China.

The Chinese Civil War (1927-1936, 1946-1949)

From the late 1920s until almost the 1950s, China was continuously at war. There was in-fighting in the Kuomintang, there was the Northern Expedition to eradicate the warlords, there was inter-party fighting between the KMT and the CCP, and there was even more fighting between the Chinese and the Japanese. Untold millions of Chinese died in what was nearly two dozen years of nonstop combat. And for half of that time, it was Chinese fighting other Chinese – the Chinese Civil War.

The origins of the Chinese Civil War go back to the Warlord Era. The Kuomintang and the CCP (Chinese Communist Party) were supposed to put their differences aside, and work together, to destroy warlords in China. This was the “First United Front”. But it was hardly any sort of unity. The KMT and the CCP were uneasy allies at best. At worst, they spent more time fighting each other, than the warlords. Chiang Kai-Shek, the-then President of China, was fearful of the communists, distrustful of their motives, and worried about the stability of his own government constantly.

After the ousting of the warlords and the final victory in Shanghai, the two rival parties, the KMT and the CCP, turned on each other, full-time and hardcore. While the rest of China got on with their lives, the CCP and the KMT, and their followers and supporters, waged bloody warfare with each other.

In Roaring Twenties Shanghai, the affluent residents of the International Settlement celebrated the opening of the Canidrome greyhound racing-track, and the adjoining Canidrome Ballroom. The year was 1928. Outside the cities of China, Chiang Kai-Shek and Mao Zedong fought battle after battle.

Despite a numerical advantage that, for most of the war, far outnumbered the communists, Chiang’s forces were unable to win. This has been attributed to corruption, and an increasing lack of foreign interest and empathy. Military and tactical blunders weakened the Nationalists, and Chiang’s own intense, anti-communist stance made him many enemies.

By contrast, the communists won support (and manpower) by making promises to the millions of peasants, whose lives had hardly changed in thousands of years. The promises of a new, modern China, and that if they followed the Chinese Communist Party into battle, their lives and living conditions would improve.

While the Nationalist forces decreased in number, these inspirational speeches caused the ranks of the Communists to swell, reaching up to four million soldiers by the time the war ended. But apart from eventually winning the war of numbers, the Communists also had more fighting-experience. They were experts in guerrilla warfare – they’d been fighting the Japanese for years using such methods. The Nationalists by contrast, had been too busy fighting the Communists.

The Long March

One of the most famous events of the Chinese Civil War is the “Long March”. This was a march undertaken by the members of the Chinese Red Army (the predecessor to the modern Peoples’ Liberation Army), while trying to evade capture by Nationalist KMT forces during the early years of the War.

The Long March was not ONE march. If you’re imagining some great procession like Moses leading the Jews from Egypt…forget it.

The Long March was actually a series of marches, stretching from 1933-1935. It was during this period, when the KMT was actively seeking out the communists in the southern provinces of China, that the members of the Red Army evaded capture, and snaked their way north and west, further inland, and further north, away from the KMT. This was the period when the KMT stood the greatest chance of winning, and the CCP had the greatest chance of losing the Chinese Civil War.

So why didn’t they?

In a word, ‘Cohesion’, or the lack thereof.

The Communists survived due to their cohesion, their determination to stick together and to fight and grow and escape to bring forth what they hoped would be a better China. The Nationalists suffered from corruption, a lack of cohesion and cooperation, and an inability to “win the hearts and minds of the people”, as we might say today.

To understand how the war affected each party, you have to understand something about China – it is GIGANTIC. It has millions of people. And far from the bright lights and jazz of the coastal cities, these millions of people lived lives which had gone almost unchanged for thousands of years. They clung to belief-systems centuries old. They lived in villages and farmed and cooked and cleaned and traded and worked in ways which had not changed in living memory. These MILLIONS of peasants were the workforce of China.

Controlling these peasants were the aforementioned warlords with their private armies. The peasants saw these warlords as their leaders, or at least their rulers. They had no interest in the KMT or in Chiang Kai-Shek. Their interest was local. Local meant their village. And their interests were what their interests had always been – farming, feeding and staying alive – an incredibly hard thing to do, with China’s notoriously unpredictable weather. Chiang Kai-Shek coming to power did not change ANYTHING about how these people lived, and Chiang was not interested in changing them. He wanted to keep China as it was. So it’s unsurprising that the peasants just…ignored him.

By contrast, the communists vowed to destroy the landlords and give the land equally to the peasants of China. Suddenly, these powerless serfs would have land for farming, for raising cattle, for building homes and lives. This made them far more interested in the communists, who would surely improve their lot! If you were a poor Chinese peasant, interested in nothing more than your farm, your crops and your animals, who would you be more inclined to follow? A man who wanted to keep the status quo, so that the wealthy and powerful could enjoy everything, or a man who promised to give you land and livestock to improve your life?

Now you might think that appeasing the peasants might not be a big deal. But there you’d be wrong. In appeasing the peasants of China, you would be drawing millions of people to your side. Whereas appeasing to the wealthy, a small minority in China, would get you precious little in terms of manpower, essential for fighting a war.

The result was that the peasants were not interested in the KMT or Chiang Kai-Shek, and they certainly had little to no interest in joining an army that would not fight to improve their lives. This meant that the communists grew powerful and the nationalists weakened.

Back to the Long March.

Surrounded by the nationalist armies and facing complete annihilation in the communist stronghold of Jiangxi Province in southern China, the communists beat a hasty retreat. The four communist armies, over the course of years, backed away, heading west, and eventually, north. Tens of thousands of men marched, on foot, through China, to escape their enemies. No roads, no railways, no motor-cars. Just a pair of shoes.

This show of determination must have impressed the peasants, who might’ve seen the communists as downtrodden nobodies, like themselves. Which might’ve inspired them to join up. The result was that the communists grew in strength as they marched. And they marched alright – 6,000 miles. That’s across the Atlantic Ocean from New York to London…and back!

So while the Long March was a retreat, it was not necessarily a failure. Because the communists were growing all the time, building strength as they stepped back.

Eventually, the four weak, but numerically-boosted communist armies arrived in Shaanxi Province, northwest of Jiangxi, and here, they could recuperate and strengthen for the struggles ahead.

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945)

A major contributing factor to why the Nationalists lost the war is a small event called the Second Sino-Japanese War. Japan, following in the footsteps of its ally, Germany, wanted what the Germans called “Liebensraum” – ‘Living room’, or ‘living-space’. Space to grow and expand.

To this end, they invaded China. Not once. Not twice. But three times.

First, in 1931. Here, they launched an attack from Korea into Manchuria, in northern China. This attack claimed Manchuria for Japan, and forced Chiang Kai-Shek to break up his army to have some troops on standby, should the Japanese decide to invade China-Proper. But the Japanese seemed satisfied, for now. They even put up a new emperor in Manchuria – the Last Emperor of China himself! Puyi, by now, a young man and former royal, eager to reclaim his throne. He’d thrown in his lot with the Japanese, hoping that they would lead him to victory.

The Shanghai Incident

The second attempt at invading China was what became known as the “First Shanghai Incident”, in 1932.

Wanting to try and claim more of China, the Japanese became increasingly interested in one city – Shanghai.

The International Settlement of Shanghai was the jewel in the crown of China. Here, Westerners poured in all their money, wealthy Chinese mingled with diplomats, businessmen, newspaper-reporters, jazz-musicians and gangsters. Absolutely anything you wanted could be got for you – at a price, of course. Drugs, sex, alcohol and gambling. All fueled by money brought in by rich Westerners eager for a slice of the Orient from the comfort of their own little corner of transplanted, reproduction Europe.

The Shanghai International Settlement in 1935. The area to the north of Huangpu River (with the curve in the northern bank) is the District of Hongkew, and the Japanese Concession. To its west are the German and American concessions (north of Suzhou Creek). South of the creek for the width of the Bund, is the British Concession. South of the British Concession is the French Concession, and the original walled city of Shanghai. Click on the map for an extremely high-resolution image!

The Japanese wanted all that.

To try and get it, they turned a series of riots, anti-Japanese attacks, and possible Chinese-Japanese racial attacks into a pretext for waging war on China. And sent in the troops. Literally.

But…how to get so many troops to Shanghai without raising suspicions? Especially after what the Japanese had done in Manchuria?

Ah!

The soldiers, the tanks, the battleships in the Huangpu River were not there to attack CHINA! No…

They were there to protect the Japanese Concession of Shanghai! Yeah, that was it! Yeah…nothing else. Absolutely nothing else.

On the 28th of January, 1932, the situation hit boiling-point. The Japanese launched an all-out attack on Shanghai. And the Nationalists and the people of Shanghai were quick to respond.

Nobody wanted to lose Shanghai. Not the Chinese, not the Japanese, and certainly not the Western expats. And for little over a month, full-scale fighting erupted in the streets of the International Settlement.

The Japanese approached the Shanghai Municipal Council, the governing body of the Settlement, demanding that they demand that the Chinese Government take responsibility for the racial-attacks against the Japanese in the Settlement. After some umming and ah-ing, the Council agreed. And it was hoped that after this, the Chinese and Japanese Armies, massed on the borders of the Settlment, and Huangpu River respectively, would back off.

And so they might have, if a Japanese plane had not carried out the first bombing ever made on Shanghai.

The Japanese poured into the Settlement, entering through the Japanese Concession in Hongkew (Hongkou District, in modern Shanghai), in the easternmost sector of the Settlement. Their grievance being against the Chinese, the fighting was largely contained to this area, and thereafter spilt out into Chinese Shanghai. The Western concessions, controlled by the Germans, Americans, British and French, remained largely untouched. In fact, some expats would even go out onto the tops of tall buildings to watch the fighting.

On the Third of March, the Chinese drove the Japanese back, reclaiming Shanghai for China! Huzzah! But it was not to last.

The third and final invasion of China happened in 1937, when Japanese troops poured into China from their new Manchurian colony. The Nationalist Armies, still fighting the Communists, were not prepared, and in a matter of months, most of the great cities of China were taken – Peking, Tientsin, Nanking, and even Shanghai.

The Battle of Shanghai was one of the strangest events in the history of China. It was taken, but not taken. Invaded, but spared. Touched but untouched.

The Battle of Shanghai in 1937 was a three-month assault on the city which saw Chinese Shanghai fall to the Japanese after weeks of brutal, door-to-door fighting. Due to Shanghai’s importance as a trade and business-capital of China, resistance and defense was stubborn and determined. But while the Japanese ravaged Chinese Shanghai, they left the famous International Settlement alone.

Policed and governed by an international force of British, French, American, German and Japanese soldiers and diplomats, the Japanese were fearful of backlash from the Western powers, should they invade the Settlement. As such, they did their best to avoid aggravating its inhabitants. In fact, the Settlement’s governing body declared its neutrality during the Sino-Japanese War, and refused to take sides.

While China collapsed around them, life in the International Settlement went on almost as it had done for nearly a hundred years before.

The Second United Front

The First United Front of the 1920s was formed between the KMT and the CCP, to drive out the Chinese warlords which held sway over much of China during the years after the fall of the Qing Empire.

In the 1930s, the KMT and the CCP formed the second “United Front”, to drive out the Japanese! But, like the First United Front, the Second United Front was united in name-only. The armies of Chiang Kai-Shek spent more time harassing the communists than attacking the Japanese, and the communists attacked the Japanese using guerrilla tactics, which both the Nationalists and the Japanese were unfamiliar with. This supposed ‘unity’ was meant to protect China and its people. But as with everything else, it simply fell apart.

Cities along China’s coast and main rivers were swept up by the Japanese and demoralised and exhausted Chinese soldiers were decimated by soldiers of the Imperial Japanese Army. During the famous “Rape of Nanking” in late 1937, thousands of surrendered Chinese soldiers were bayoneted, shot, or beheaded, under the justification that the Japanese did not have anywhere to keep them prisoner, nor the resources to imprison them and feed them.

As before, the Second United Front collapsed due to Chiang’s paranoia regarding the communists. In fact, he never wanted a Second United Front. It only happened because he was KIDNAPPED by OTHER NATIONALISTS, who forced him to see sense, that the Japanese were a bigger threat than the communists. But even then, it still didn’t work, and the KMT spent more time attacking the communists than the Japanese. By 1941, the ‘United Front’ had completely collapsed, destroying any further chances for both the KMT and the CCP to work together to rid the country of the Japanese.

The Day of Infamy

December 7th, 1941.

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. They also attacked Guam, Malaya, Wake Island, the Philippines and Hong Kong. But one location not mentioned in President Roosevelt’s famous speech, is the Japanese assault on the Shanghai International Settlement.

Commenced just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the world-famous Settlement, for years already living on borrowed time, was finally invaded by the Japanese. Extraterritoriality be damned. The treaties that had protected Westerners in China were now useless, and overnight, the Settlement was dragged into the war that it had tried, for nearly five years, to avoid.

The residents of the Settlement panicked and fled for the Port of Shanghai. Here, those with money, passports, and other necessities for travel, managed to book or bribe passage on an evacuation-ship out of China. For any Chinese who had sought refuge under the cloak of the Settlement’s neutrality status, their last vestige of protection was blasted to pieces by Japanese artillery-fire. Facing overwhelming odds, the Chinese defenders were swept aside and the Japanese formally occupied ALL of Shanghai.

From 1941-1943, the Settlement existed in a sort of limbo-status. Not in Western control, not in Chinese control. In 1943, the British formally signed the land of the Settlement back to the Nationalists, ending 100 years of Western residence in Shanghai, and returning the city center to the people of China.

The result of this was that any Westerners in Shanghai who had not been lucky enough to escape on a ship during the invasion, was now a ‘stateless refugee’, to use the terminology of the time. They were Shanghailanders no-more. And as such, were rounded up and sent to prison-camps, where they would have to wait for the end of the war.

The Continuation of the Civil War

In 1945, the Second World War ended. The Chinese were driving the Japanese out of their homeland, and on all fronts, the Japanese were being beaten back to their home-islands. The United States Army Air-Force rained bombs on Shanghai to try and force the Japanese to evacuate the city. But while the World War was over, the Civil War was not.

In 1946, it started again in earnest. And this time, the Nationalists were on the losing side.

Weakened by seven years of war with the Japanese, the Nationalist force was a fraction of what it once was. The Communists, strengthened and more experienced after using guerrilla tactics against the Japanese, now outnumbered the Nationalists. Defeat after defeat saw the Nationalists fall back, eventually evacuating to the island of Formosa, formerly a Japanese colony, where the Republic of China was then established in what is known today as “Taiwan”.

On the 1st of October, 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the creation of the People’s Republic of China, in Beijing. Chiang Kai-Shek and his nationalists evacuate the mainland and set themselves up in Taiwan. The war ends in May, 1950.

The Great Leap Forward

When you think of events that have shaped or influenced modern China, you can’t go past the Great Leap Forward. Probably better named as the Great Stumbling-Block.

After winning the Civil War, the communists had to legitimise their rule of China. To do this, they had to prove that they could do things that would improve the lives of ordinary Chinese people. And to do that, they started what they hoped would be a powerful and nation-changing industrialisation and agricultural revolution. They called it the Great Leap Forward.

Started in 1958, the Leap Forward ended in 1961 as an unmitigated disaster and is one of the worst chapters in modern Chinese history. Its catastrophic failure saw tens of millions of ordinary Chinese peasants, who had originally supported the Communists, die of starvation. But what was the Great Leap Forward and what happened to it?

Even in the 1950s, China was still a largely medieval society. Away from the bright lights and bustle of the major coast-or-river-hugging cities, life for millions of Chinese carried on as it had for centuries. The Communists hoped to improve the lives of people by mass farming, large-scale agriculture, high-volume steel-production and vast collectivisation. To this end, Chairman Mao started the Great Leap Forward.

Despite the good intentions and results that the Great Leap Forward had, and had hoped to achieve, everything was against it.

Experiments in agriculture, irrigation, crop-planting, plowing and harvesting were disastrous. Carried out on such a large scale across China, all it took was one hiccup to destroy everything. And everything was indeed, destroyed. Although propaganda films showed enormous crops and bumper harvests of rice and other grains, the truth was that these quotas and harvests were all bogus. And because private farming and land-ownership was now forbidden, the peasants, who now had to rely on the State, could not revert to their traditional ways of farming or land-management, which had been their safety-net in earlier times.

Collectivisation and communes, the methods with which Mao Zedong hoped to move China forward worked well in theory, but not always in practice. They relied on teamwork – Communes were communities made up of several dozen families. And they would work together, collectively, to feed, farm, clothe and support each other. This might have worked to some extent, but the failure of the government-enforced farming-practices doomed these efforts to failure.

Under the Great Leap Forward and the commune and collectivisation systems, the skills of the peasants, who had been living rural, farming lives for countless generations, were now ignored. Government officials in Beijing decided how the land would be farmed. They decided everything. And I do mean EVERYTHING. What crops would be planted. Where they would be planted. How they would be planted. What fertiliser was to be used, how they would be irrigated, and everything else. The skills of peasants who had been doing this kind of work for centuries was ignored. Instead, their work was dictated by politicians who had absolutely no practical experience of farming. The result was an absolute disaster, as crops failed and harvests dwindled into insignificance.

How it was supposed to work was simple: Every commune, through collective efforts, was supposed to produce food and reach a certain quota. Of this, a percentage was taken as tax, to feed people in the cities, and party members. The rest was distributed amongst the peasants in the commune. But the agricultural quotas set out by the Chinese Communist Party were outrageously high. And the amounts of grain ‘supposedly’ produced by each commune were all falsified, in an attempt to show just how effective the Great Leap Forward had been. This meant that when grain-taxes were collected, the peasants were left with absolutely nothing to eat! The Party’s already bungled farming-practices had robbed the peasants of their skills and their land. And now, giving up crops that they didn’t have to show how “bountiful” their land was, also robbed them of what little food they had been able to grow.

The result was the Great Chinese Famine, in which, depending on what you read, 15-55 MILLION PEOPLE died, from starvation. Due to large-scale crop-disasters.

This was partially due to the misguided farming practices, partially due to the weather, but also partially due to another goal of the Great Leap Forward, which was the large-scale production of steel. To this end, ordinary Chinese people had been encouraged to build blast-furnaces in their backyards. Or in their fields. And produce steel.

You.

Yeah you. Reading this.

Go out. Right now. Into your back yard. Build a furnace.

Make steel.

What happened?

Just like you, the millions of Chinese forced to do this as part of the government’s official scheme, had not the faintest idea how the hell to make steel. Let alone steel of any decent quality, or great quantity. It was brittle, it cracked, it was useless for anything!

And worst of all, it meant that there were now even fewer people around to tend to what few crops had actually been grown and tended to successfully, which meant that they died due to neglect, which meant there was even less food than the already dismal amounts produced, which contributed greatly to the Great Chinese Famine of the period 1959-1961.

The Great Chinese Famine was a famine in the truest sense of the word. With absolutely nothing to eat, with all their grains taken by the government after the monumental screw-up of the farm-quotas, or sent to Russia to pay off China’s massive debt to the Soviet Government, the peasants of China, millions of them, had nothing to eat. They lived on literally whatever they could put into their mouths. Grass. Leaves. Tree-bark. Even soil or mud. Anything at all that they could persuade themselves to swallow was to be considered food, in the place of their actual food-staples, none of which now existed.

As much as they tried not to admit it, even the Chinese Communist Party had to accept that the Great Leap Forward, despite all its good intentions, had been a disaster of unprecedented and horrific scale. It was officially ended in 1961, and was followed by another of China’s great revolutions.

The Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)

Or, as my old highschool Chinese teacher used to say: “The ‘So-Called‘ Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution”.

My Chinese teacher was not a fan of the Cultural Revolution. Probably because it involved his father being arrested as a political enemy and thrown in prison. A fact he shared with us, bright-eyed teenagers when we were studying history in school.

The Cultural Revolution was started by Mao Zedong in 1966 after losing face in the eyes of his fellow Communists, due to the catastrophe of the Great Leap Forward. It was designed to reinvigorate the nation, remind it of the great communist struggle to improve China, and to cleanse the country of the years of darkness and depression that had plagued it since the Civil War.

To try and reinvigorate the nation, Mao opened the floor of the country to anyone who wished to criticise. He wanted the youth of China to speak freely, vent their feelings, and attack anything that they felt was anti-communist or against the Party. Writers, journalists, artists, school-teachers, politicians and government officials were all denounced.

The youth of China were encouraged to become “Red Guards”, ideological protectors of communism and socialism, who lived their lives according to the quotations in contained in the famous ‘Xiao Hong Shu‘ – the Little Red Book. Or more properly: “The Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse Tung“.

The book, written by Mao himself, was a series of quotations of his own, from speeches and other writings, designed to inspire and give the youth of China something to follow and aspire to. The book received its nickname because of its pocket-sized format, and bright red cover, designed to be easily carried, stored, and immediately recognisable to anyone in China. Considering the population of China, it’s unsurprising that the Little Red Book is one of the most widely-printed books in the history of the world!

The Cultural Revolution was not just an attack on structure and politics, it was also an attack on the traditions and culture of China. Anything old, or to do with old China was attacked. These were considered detrimental and unhealthy, and did not improve the country. Ancient practices related to funerals, marriages, religion were systematically banned. Even the works of China’s most famous philosopher, Confucius, were placed under direct attack. The playing of mahjong, the most famous Chinese game in the world, was banned during the Revolution, due to it being an “old custom”.

For a period of ten years, the youth of China, boys and girls who were of an age attending highschool, or who were university students (broadly ranged from young teenagers to those in their mid-twenties), wreaked havoc on China. The desire to prove loyalty and to rid the country of “closet capitalists” and other people who might be ‘anti-revolutionary’, caused a complete breakdown in social order. By 1976, things were totally out of hand. It was only the death of Chairman Mow in that same year, and the change of government, that finally stopped the movement.

The Opening of New China

Just as China in the mid-1700s was being opened up to the West, so was China in the mid-1900s being re-opened to the West. After the disasters of the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution had left the country weak, shaken and exhausted, reforms swept across China, in a desperate and concentrated effort to haul the country back from the brink, and to return some sort of sensibility and normality, stability and security to the lives of ordinary Chinese people.

Led by reformist politician, Deng Xiaoping, China was to become a more stable and open country. The Open Door Policy of 1978 encouraged trade and foreign investment in China. Barred from entry and scared away by decades of instability, foreigners, who had largely never set foot in China since the end of the Civil War, slowly returned. In 1950, on the 25th of April, the American Consulate in Shanghai closed its doors. Almost exactly 30 years later, on the 28th of April, 1980, the American Consulate in Shanghai was re-established, hoisting the American flag and opening its doors to business. The flag raised over the consulate in 1980 was the exact same flag which was lowered from the consulate roof when it was shut down in 1950, kept in storage for 30 years!

To restore the people’s confidence in the government, and to show the people that they actually knew what they were doing, reforms based on tried and tested methods were introduced. One of the most famous ones was a reaction against the Great Leap Forward. It was called the Household Responsibility System.

Under this system, rural Chinese living in communes were given large plots of land. This land was divided up among them, with each family or household owning one plot. The family was responsible for the upkeep and farming of this plot of land.

Unlike in the past, where families and farmers had to try and meet ridiculous quota-systems that left them with nothing to eat, under the new system, farmers could now work their own land as they saw fit, to get the highest yield. They kept whatever they could eat, and sold the surplus to the state, to feed the masses in the cities. They were responsible for the land’s upkeep, its use, and its cultivation and harvesting. The State took a back seat to agriculture, unlike in the 1960s. This new system, established in the 1980s, has allowed many farmers in China to improve their standards of living, by embracing the growing market economy of China.

Reforms in China during the 1970s and 80s have gradually opened the country up to the world once more. Although some would argue that China still has a long way to go, in the past thirty-odd years, it has made dramatic changes. In the 21st century, China is once more a world power, much as it was in times of ancient history.

More Information?

“The Long March” (U.S.) 2-Part documentary-film

“Nanking” (documentary film)

http://www.jianshixue.com/ – “A Short History of China” (1900-1949)

http://www.jianshixue.com/1939-1945-the-resistance-w/1936-1941-the-second-united-front.html – “The Second United Front”

“Mao’s Great Famine” (documentary film)

“The Cultural Revolution”

Shanghailander.net – This is one of the biggest blogs on the internet about the Shanghai International Settlement, and pre-revolution China in general.

The Chinese Household Responsibility System