Here’s an idyllic, family scene, isn’t it? A little boy or a little girl crawling into his or her’s grandparents laps, cuddling them while the old folks whisper sweet things into their ears and tickle them and give them cuddles…

…eventually, that little boy or little girl asks: “Momma…Papa…what was things like when you were my age?”

Grandparents smile, glad to know that their offspring’s offspring is fascinated with what they have to tell them. So gramps, nanna…what were things like when you were a child?

This year, we proudly celebrate the first decade of the 21st century. But what was it like 100 years ago, back when people were celebrating the first decade of the 20th century? Here’s a few things that used to be, that were commonplace, but which have changed drastically or which have disappeared completely from daily life. How many do you know, or remember?

The Traditional Wet Shave

These days when most of us shave, we think little of it. We turn on the razor, or we click a cartridge into our Mach 3 or our Gilette Fusion and scrape and buzz away like we’re trying to remove varnish from floorboards with a belt-sander. But things were very different back when grandpa was a child. How was it done without fancy, high-tech gizmoes like those eletric buzz-saws we call ‘razors’ today?

Back in the old days, a man tackled this, usually daily task, with something called a straight-razor…

Pretty, innit? A straight-razor (also called by the charming name of a ‘cut-throat’ razor) was the main shaving-tool from about the 18th century until the early 1900s. Straight-razors were kept literally ‘razor sharp’. They required considerable maintenance and a fair bit of skill to use. It used to be that grandpa or great-grandpa would hone and strop his razor at home in the bathroom to keep it sharp. Straight-razors had scoop-shaped blades so that as you shaved, the blade scooped up the shaving-soap and cut stubble as you shaved. Stropping and sharpening took up a fair bit of time. You sharpened the razor against a whetstone or a honing-stone and then you stropped it against a leather and canvas strop, to keep the edge sharp and even. Failure to sharpen and strop your straight-razor properly resulted in cuts or nasty razor-burn! Yeouch!

A shaving accessory of the particularly wealthy men of the 19th and early 20th centuries was to own one of these:

They’re seven-day razor sets, one blade for each day of the week. By using a different blade for each day of the week, the razors required less stropping and honing and sharpening. Of course, with so many more razors, when it did come to having to maintain them, it took a considerably longer time to do so. But if you could afford a seven-day razor set, you could probably afford to pay a valet (a personal manservant) to do all that tedious razor-maintenance for you.

Along with the brush and the blade, you also had shaving-soap. Not cream, soap. You had a cake of soap and a shaving-brush…

Cute little fellah, innie? You used the brush to apply the soap to your face, moving it across your stubble in a circular motion to lather up, spread the soap around and hydrate the skin and lift up the stubble. The brush also scraped away any dead skin. Then, you shaved.

Of course, some people preferred using the new double-edged ‘safety razor’ that came out in 1901. They look like this:

Safety-razors were popular because they were…safer! And they didn’t require as much maintenance. King Camp Gilette, the guy who came up with the safety-razor, cooked up a business-deal with the US. Army. When soldiers headed off to war in 1917, they were all given safety-razors, which led to its widespread introduction into civilian life later on, replacing the straight-razor.

Some people still shave with straights and safeties. They provide a better shave and they cost less money in the long-run. If you can find a vintage blade-sharpener, a single safety-razor blade can last for months, a straight-blade, properly looked after, lasts indefinitely, whereas you’re throwing away and buying cartridge-blades every month. I made the switch to shaving with an old-fashioned safety-razor as a new year’s resolution in early January, and I am never going back. If you want a better shave, go back to basics.

Preserving Food

Have you ever heard your grandparents call a refrigerator an ‘icebox’? Have you ever wondered what an ‘icebox’ was? How did people keep food fresh back in the old days without modern preseratives and refrigerators and all that fancy stuff?

Like me, you probably thought that this was an icebox:

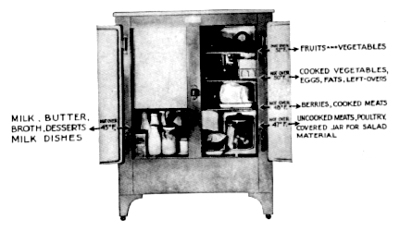

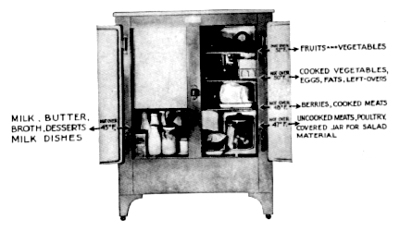

Sorry folks. That’s an ice-chest (also called an ‘esky’). THIS is an icebox:

Iceboxes were common in homes from the 19th centuries until the mid 20th centuries, when home refrigerators finally became practical. It’s a handsome piece of furniture, isn’t it? But how did it work? Did it really have ICE in it!?

Oh yeah. It had ice. Back in the day, the iceman, a neighbourhood institution, would come by your house every week or every two weeks, with a block of ice. He’d come into your kitchen and put the ice into the icebox, close it and head out on his way. The block of ice (which was huge) would keep the food and drinks in the icebox nice and cold and fresh. In the photograph above, the ice went into the top left compartment. The compartment on the right was for regular food-storage such as bread, vegetables and leftovers. The compartment on the bottom, directly underneath the ice-chamber, was for food that had to be kept absolutely freezing cold; foodstuffs such as meat, poultry, fish and dairy-products were put here, to make the most of the chilled air circulating downwards from the ice-compartment above.

If the doors on the icebox above were opened up, this is what you would see

The bottom of the icebox generally had a removable metal pan where the melted water dripped into. This had to be emptied once every day or every second day (depending on the size of the box). Insulation in the box was provided by plates of zinc which kept the cold in and made everything nice and chilly. The huge blocks of ice which the iceman sold to you were kept in massive ‘ice-barns’, huge, insulated buildings where the ice could be stored until it was delivered.

Your friendly neighbourhood iceman. The thing in his hands are the ice-tongs, which he used to handle the MASSIVE blocks of ice, which you can see in the photograph. They often weighed several pounds each

As there was only so much stuff that could fit into the icebox, some food was generally delivered fresh every few days. Dairy products such as milk, butter, cheese and cream were delivered by the milkman, or you purchased them down at the local dairy. The baker’s boy might deliver loaves of bread. But once the food was home, it was your job to make sure it lasted.

Dumping the stuff into the icebox wasn’t the only solution grandpa came up with to keep his food fresh. Food was also smoked in a smokehouse to preserve it, it was dried, pickled, jarred or even canned! And all this was done at home, in the kitchen. Have you ever bought a little jar of fruit-jam and noticed that it says something like “Strawberry Preserves” on the bottle? That’s not just fancy marketing…that’s what it is! It’s preserved strawberries, by turning them into jam and putting them into an airtight jar to keep them fresh!

Schooling

Schooling has changed a lot since our grandparents were kids. These days we have computers, detention, graphics calculators and learning software to teach us. Back in the early 20th century, teaching was done with a book, a slate, an inkwell and the rod.

Flogging children for misbehaving in school has existed for centuries, and it was only recently abolished in some places. Children could be flogged for almost anything from spilling ink to talking in class to breaking a pen-nib by accident and not having a spare one! (Roald Dahl was flogged for this last, horrific offense).

Schooling was simple, but effective. It concentrated on the ‘Three R’s. What are they? Reading, WRiting and ARithmetic. Or in other words, English comprehension, penmanship and mathematics. Penmanship is a dying lesson in school these days, but back in the old days, you HAD to have nice handwriting, and you were beaten if you didn’t. Teachers used to force lefthanded children to write with their right hands. Why?

There are several theories about this, ranging from devil-worship and sinister evil to bad posture, but there is actually one very simple explanation: The pens.

Until the 1950s, children in school wrote with dip-pens, using liquid ink and inkwells. Dip pens write very wet and glossy on the paper. Writing with the left hand smudged the still-wet ink all over the page, something that right-handed scribblers had no problem with, since they wrote AWAY from their writing, moving across the page from left to right. To prevent the smudging and to encourage neat handwriting, teachers forced children to write with their right hands instead of their left.

Soft Drinks

These days, we don’t give much thought to soft drinks. They come in metal cans or they come in plastic bottles, we open them, we drink them, we burp, we throw them away. We think of them as modern inventions. But they’re not, are they?

Back in the old days, soft drinks were very different. Apart from being cheaper, they were also manufactured and marketed very differently. Coca-Cola, created in 1886, was first marketed as a medicinal syrup! By the early 1900s, it was a popular everyday beverage. Why is it called ‘coca’ cola? Because one of the chief ingredients used to be the product of the coca plant…cocaine! And you didn’t always buy ‘Coke’ in bottle form, either. It used to be that you went down to the local deli, drugstore, cafe, bar or diner and it was served ‘fresh’ to you, specially mixed from a soda-fountain. Coke was first sold in bottles in 1894 (the first experimental bottlings had started a couple of years before in 1891), but in most small towns, you could still order Coke ‘fresh’ out of the soda-fountain, served up to you by an occupation that has since disappeared, along with the soda-fountain…no this isn’t rude, it’s the actual job-title…but a fellow known as a ‘soda-jerk’ used to serve you your fresh, fizzy coca-cola, straight from the fountain. Soda-jerks probably got their name because they were constantly ‘jerking’ on the pump-handles which operated early soda-machines.

Thirsty? A soda-jerk serving up a nice cold one from an old-fashioned soda-fountain

But what if you didn’t have the money to buy soft drinks? What then? Believe it or not, people used to make their own soft drinks! Yep, right at home in their kitchens. Mostly, it was lemonade or limeade, or other fizzy or sweet drinks made from the juice of various citrius fruits. You took lemon-juice, sugar, water and baking-soda (that’s Bicarbonate of Soda or Sodium Bicarbonate) and mixed the ingredients in correct quantities. You left the mixture to stand for a while, to give the baking-soda time to react with the lemon-juice and the other ingredients, the result being that it fizzed up, to create fizzy lemonade. You can still make homemade lemonade like this, and recipes are available on the internet. Some substitute the baking-soda and water for soda-water instead, but the results are all similar. Fizzy, sweet, lemon-flavoured goodness on a hot summer’s day.

Public Transport

These days, we hop on a train, or a bus…we don’t think much of it. But public transport was very different back in the eras when our grandparents and great-grandparents were alive. In the early 1900s, buses as we know them today did not exist. Trains were steam-powered or powered by electricity. Electrically-powered trains ran on very short lines, usually confined to servicing a given city or town, not used to travelling great distances. So, what forms of public transport existed in town back in the early 1900s?

Trolleycar, cablecar, streetcar…tram

Call it what you will, from the 1870s until the 1950s, the streetcar (American English) or the tramcar (British English) was a fixture on many main roads throughout towns and cities around the world. The first trams were horse-powered, but were soon replaced by the safer, more advanced and controllable cable streetcars, which made their appearance on the streets of the world in the late 1870s. Cablecars were powered by a cable in the ground. The car rode on two tracks with a ‘grip’ (a clamp) which went underneath the car, to grab onto a cable set into a special metal trough between the rails. By gripping the cable, steam-power which turned the wheels at the cable-car barns at each end of the line, pulled the cables and pulled the cablecars along as well. The inventor of this ingenious system of transport was inspired to create it after he saw a heavily-loaded horse-tram go sliding backwards down one of the steep and slippery streets of San Francisco, where these antiquated old streetcars are still a major tourist-attraction.

This black and white photograph of a San Francisco cablecar is representative of the type of public street-transport that existed in many American cities throughout the last quarter of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th century. Streetcars such as this grabbed a moving cable in the ground, between the streetcar tracks and they were operated by a two-man team: The gripman (seen on the right in this photo) and the conductor (on the left, by the door). Operating a streetcar of this kind required considerable body-strength, since everything was done mechanically and by sheer muscle-power. It was the conductor’s job to look after the passengers and collect fares and issue tickets. It was the job of the gripman to control the cablecar and work the levers which operated the grips (the clamps which grabbed or released the moving cable). It was also his job to operate the brakes and sound the cablecar bell to alert traffic.

In the 1920s and 30s, streetcars began to change. The old-fashioned cable-pulled, steam-powered streetcars were out of date by now. While they continued to exist in some places, many began to be replaced by the faster, more quiet electric trams, which ran along the streets, powered by overhead cables which delivered electrical power to the tram’s motor. They were able to move to more places and do it more efficiently. They had enclosed passenger cabins which had doors that were opened or closed by pneumatic pressure.

‘W’ class trams from Melbourne, Australia such as this one, were fixtures on the streets of the city from the mid 1920s until they were recently discontinued in 2009

Streetcars or trams were a popular and common sight on the streets of many cities around the world until after WWII. In the Postwar World of the 1950s and 60s, people considered trams old-fashioned, noisy, clanky and inefficient. Many tramlines were closed down, the tracks were ripped up or paved over, and bus-routes replaced them. In a select few places, however, such as Melbourne in Australia, San Francisco in America and various towns in Germany, trams or streetcars still exist as a form of practical public transport.

Elevated Railways

Elevated railways are a fast disappearing form of public transport. They used to be really common in the United States. Elevatated railroads ran on steel supports that held the train-tracks up above the roadways which the trains had their routes. Elways were proposed in the second half of the 19th century in the USA. The Industrial Revolution had caused a significant rise in traffic in many major American cities such as Chicago and New York. City planners and transport officials were struggling to find a way to move people around quickly and efficiently and most importantly, in a way that would get them off the streets!

Trains were considered the best way to transport people around, but digging a subway wasn’t always the best option. If you couldn’t go under, then you had to go over. Elways were born.

A typical elway track was supported on a steel frame high off the ground, usually on a level with a building’s first or second floor. This allowed sufficient space underneath for large vehicles such as trucks, buses and streetcars to move underneath without fear of damaging the supports. Elway stations were accessed by staircases that led you from street level up to the raised platforms where you could wait for the train.

A typical elevated railway station (this one located in Chicago, Illinois)

Original elway trains were steam-powered. But as you can imagine, this was ineffective up in the air, where hot coal, ashes and water could spill down into the streets below, so steam trains up in the air didn’t last very long. They were soon replaced by electrically-powered trains, which look very similar to the kind which you see in movies like “King Kong”. They were basically subway trains dumped on tracks which were stuck twenty-five feet up in the air on metal supports.

Elway trains lasted as a means of transport for several decades, but, like streetcars or trams, they were gradually torn down during the postwar years, due to a combination of lower passenger loads and changing forms of transport. A few cities,, such as Chicago and New York in the USA, still have elevated railways, but their presence has much deminished from the 30s, 40s and 50s when they were a common sight around many large American cities.

Communications and Correspondence

SMS, telephones, cellphones, email, Instant Messaging, Skype, Twitter and Facebook…these days we have so many dozens of ways to communicate. We seem to forget that not too long ago, none of this stuff existed, and that if we lived 30 or 40 years ago, we’d be stuck back where our grandparents and great-grandparents were, communications-wise, over seventy years ago.

So, how did people communicate before our modern mumbo-jumbo?

Letters

“…I’m gonna sit right down and Write Myself a Letter…” – Fats Waller

Yep. Snail-mail, as we like to call it today, was the main method of communications back when our grandparents were our age. These days, most people have never written a letter. I don’t mean typing an email, I mean actually writing a letter. With a piece of paper, a pen, a stamp and an envelope. This was how it was done back in the “old days”.

“But it’s so slooow!” you wail.

It is today, sure. But back then it was remarkably fast, even by the standards of the day. Post was delivered a lot more frequently back in the old days than it is today. These days, it’s distributed and sent out once a day. Back in the 1900s, 1910s, 1920s and the 1930s, post was collected and delivered a lot more frequently. In the Victorian era, post was gathered several times a day. The first post was done in the morning. Then at noon, then in the afternoon, then around dinnertime and then the “last post” in the late evening, before midnight, before it all started again the next day.

Telegrams

Telegrams seem funny to most people these days. How could anyone seriously hope to send a message that read something like:

“Coming into town Monday” STOP

“Meet me at station 2:30” STOP

“OOXX to Mary” STOP

Starting in the 1840s and not finally ending until the very early 21st century, telegrams have been one of the longest serving forms of communication in the world. In fact, Western Union, a company more famous today for processing money-orders, used to be the chief provider of telegrams, sending, recieving and processing millions of them every day, a service that they stopped less than ten years ago!

To understand why telegrams were so popular, you have to understand what it meant to communicate any other way.

Communicating by mail was cheap, but it took a long time to get a reply, but, you could write whatever you liked in your letter. Telephones were very fast, but a long-distance phone-call was very expensive…assuming you were lucky enough to OWN a telephone, most people didn’t. And if you did, you probably had a ‘party line’, meaning that you shared a telephone line with at least one other person. You had a specific ring-tone to your telephone so that you knew when to pick it up if there was a call. Telegrams were fast, efficient and cheap, although the messages that you could send on them were short and were able to be read by almost anyone! In the 1920s and 30s, more telegrams were sent long-distance than long-distance phone-calls!

The limited space available on telegraphic forms, combined with the payment method for telegrams caused people to write their messages to be as short and as to-the-point as possible. All unnecessary words and letters were removed to cram as much information as you could into the smallest possible space. This led to a phrase called “telegraphic English” or “Telegram-Style” English, which referred to the clipped, precise English used in telegrams.

Ever wondered why telegrams always read:

“Congrats on new baby” STOP

“Will come and visit nxt wk” STOP

“Love Dave & Sue” STOP

Telegrams were charged by their length, in words and letters and punctuation. Rates and fees varied over time, but usually, it was a set rate for the first ten or a dozen words, (say, 5c), and an additional 1c for every word after ten. So a message taking up twelve words would be 7c in total. Punctuation marks such as commas, full-stops or question-marks cost extra (they were harder to send over Morse Code). Because of this, they were often avoided altogether, and the ends of sentences were marked with the word ‘STOP’.

A typical Western Union telegram

Telegrams were generally delivered by postmen, private messengers or by telegram messenger-boys, who were young lads employed by telegraph offices to send telegrams from the office to their intended recipients as fast as possible. In WWI and WWII, telegrams were used to notify next-of-kin of the death of a loved one in battle. Being a cheap and effective means of communication, telegrams were sent in their thousands to the wives, sisters and mothers of dead soldiers, generally accompanied by the nervous and hesitant telegram messenger-boy, who had the task of delivering the sad news.

Typewriters

Of course, you couldn’t always handwrite stuff. What if you were handing in the draft of a big novel or a report on the importance of thermal underwear to your boss? You couldn’t handwrite the entire thing! What if your handwriting sucked and he couldn’t read it? Well, then you would have to type it, on granpda’s response to the PC, the humble mechanical typewriter…

The typewriter went out of the office and the home study in the 1980s with the coming of the Personal Computer, but back in the old days, this was a key business machine, as essential in the 1930s as a laptop is today. Typewriters are fun to use, but they require a bit of skill and a certain level of finger-strength to operate. The majority of typewriters that your grandparents probably grew up using were the old-fashioned mechanical or manual typewriters. These machines were made of metal and plastic and they were incredibly clunky and heavy. Typewriters allowed you to write faster than you could with a fountain pen, they produced neat lines of text, but without a ‘delete’ button, you had to be a very good typist before you could use one effectively. When you used a typewriter, you scrolled in a sheet of paper and pushed the carriage (that’s the thing on the top that goes back and forth) all the way to the right, so that you started on the left side of the page. As you typed, each keystroke sent a small metal hammer up to strike the page. The hammer hit a cloth ribbon which was saturated with ink. When the hammer hit the typewriter ribbon and then the paper, it left a neat little mark there, corresponding with the mark on the hammer.

As you typed, the carriage moved across the top of the typewriter. At the end of the line, a bell rang. This indicated that you were to finish the word you were typing and then push the carriage back to the right again. Some typewriters had ‘backspace’ keys which allowed you to go back a space to type over any incorrect words.

But what if you had to type out several copies of something? Grandpa would’ve used something called ‘carbon-paper’.

Carbon-paper is a type of paper which leaves marks on anything that it’s pressed against. Grandpa had one sheet of regular paper, one sheet of carbon-paper and then another regular sheet of paper on top. He rolled all three sheets into the typewriter and set to work. As he typed, the keystrokes would hit the first page, and the impact of the hammer-strike would cause the carbon-paper to leave a mark on the second page of this little paper sandwich. When the document was done, you had one ink copy, one carbon copy and one used-up sheet of carbon-paper.

Of course, it was necessary to change typewriter ribbons, and this could easily be done by removing the reel and fitting in a new reel. Typewriter ribbon-reels were purchased down at your local stationery store, along with all your other office supplies. Most ribbons were two-tone ribbons. Half of the ribbon was red and the other half was black. You had a switch or lever on the typewriter which moved the ribbon up or down, depending on whether you wanted to type something a different colour.

Typewriters generally came in two different sizes, gigantic clunking ‘desktop’ models which were almost as big as the PCs that replaced them…

An ‘Underwood’ desktop typewriter

…or the smaller ‘portable’ typewriters, which could fit snugly into a specially-made carrying case, a bit like a briefcase:

A smaller portable ‘Remington’ typewriter in its carrying-case

Most people used the smaller, portable typewriters purely because they were convenient and saved space, but for places where typewriters were permanent fixtures, like secretary’s offices or large business-firms, the larger desktop models were used.

A lot of terminology from the mechanical typewriter has continued to be used in the computer age. Just open up a new email blank in your Hotmail account, or have a look at your keyboard right in front of you. Maybe you see a key that says ‘Return’ or ‘Enter’? Or ‘Shift’? Or ‘Backspace’?

‘Return’ was the CARRIAGE RETURN key on the electronic typewriter which came in the 1960s and 70s. Pressing it returned the carriage to the starting point. ‘Enter’ entered a new blank line on the page so that you could continue typing.

We all know what ‘Shift’ does. That gives us nice, big capital letters. On a typewriter, the ‘Shift’ key literally SHIFTED an entire set of typebars! Moving the lowercase letters out of the way and bringing in their uppercase relations. The ‘Backspace’ key moved the carriage back one letter-space for you to type over any mistakes.

Fountain Pens

When your grandfather or great-grandfather, or maybe your parents were younger, the ballpoint pen didn’t exist. Or if it did, it was looked upon with suspicion and displeasure, since early ballpoint pens leaked their filthy, disgusting paste ink all over the place. From the 1880s until the 1950s, the fountain pen ruled supreme. There are many people who still think that it should…I’m one of them; I’ve been using fountain pens for nearly 20 years and collecting them for nearly five years now. Fountain pens are very long lasting (I’ve got pens in my collection that are nearly 100 years old and work perfectly), they’re stylish, they’re cool, they write wonderfully and they’re smooth and effortless, gliding across the page allowing you to concentrate on what you want to write, rather than whether or not your pen is getting the ink onto the page!

Keeping Time

These days, almost everything has the time. Your computer, your mobile phone, the clock in your car, your blackberry, your iPhone…everything does! But back when the only timekeepers were mechanical tickers, how did you keep time? And how did you know the right time?

The Pocket Watch

A hundred years ago, men didn’t believe in wearing wristwatches. Wristwatches looked like bracelets. And who wears bracelets?

That’s right, the ladies! No self-respecting man back when our grandparents were kids, wore a wristwatch! It wasn’t the done thing! So instead, men wore pocket watches, with watch-chains and fobs. These days, we have all kinds of heavy, chunky metal watches with dials for the day of the week, the day of the month, what second it is and so on…and we think they’re new.

But they’re not.

Pocket watches had this, and more, back when our grandparents were kids. Chronograph chronometer pocket watches had all kinds of bells and whistles, everything from repeaters (little gongs inside the watch that chimed the hours and minutes), moonphases, days, dates, months and more. If you think something is new, think again.

This 1902 Patek Philippe 18kt gold-cased pocket watch was made for Tiffany & Co. It sports a minute-repeater, a stopwatch function and a seconds subdial (which was standard for most pocket watches). The little lever on the bottom of the watch (on the left) activated the minute-repeater while the button on the top left activated the seconds hand to use the stopwatch feature

Pocket watches lasted a long time, not finally ceasing regular production until the 1960s. Many fine pocket watches are kept in families and are handed down as heirlooms, which is what most of them are these days. But be brave and take out your antique pocket watch and wear it anyway! Don’t forget that these weren’t always antiques; they were meant to be used! I own two pocket watches and wear them regularly.

The Wristwatch

The wristwatch came out in the 1910s after WWI. Originally shunned by most people (who continued to wear pocket watches regularly well into the 1950s), the wristwatch soon gained acceptance amongst the world’s men and women, being sold for a long time alongside equally stunning pocket watches. Women’s watches were small and petite, often no larger than a small coin (even smaller than a quarter!). Men’s watches were also rather small. The 1920s-1940s saw the rise of the ‘tank’ style watch, which was very popular because it was so unique. Instead of being round, it was square or rectangular and it’s a wristwatch style that remains popular to this day.

A 1930s gold-cased ‘tank’ style Hamilton wristwatch

Wind-up watches

If your watch has died on you, you may hear your grandfather absent-mindedly tell you to wind it up. My grandmother used to tell me that!

All watches back then were mechanical. You had to wind them up every morning for them to keep accurate time. There’s no reason why you can’t wear a mechanical watch, many people still do…I do! But if you decide you want to wear your grandfather’s pocket watch or wristwatch, be sure to treat it carefully. Don’t bump it or drop it or get it wet. And like your car, get it serviced regularly. As a rule, a mechanical watch in regular use should be serviced once every five years. Don’t expect your watch to keep amazing time, instead, be amazed by the time that it keeps. My regular pocket watch, seen in this photo here…

…keeps time to a minute a week, despite being over 100 years old and on the lowest end of the scale of decent quality pocket watches. Don’t think that old = bad. Old might also mean great, just superseded by something greater.