Clothing is pretty important. Chances are, if you’re reading this, you might just, quite possibly, be wearing some.

I hope.

And if you’re not, then I hope that you look better without them than with them.

Anyway, since the dawn of time, mankind has had to wear clothing. Not having excessive amounts of body-hair to keep us warm meant that we had to find something else to compensate for this when the weather turned, or got wet or windy or otherwise unpleasant. In this posting, I’ll be looking at the gradual evolution of clothing from its earliest roots, up to the early 20th century, when the types of clothes we wear today started being created. So, where to begin?

Furs and Pelts

The earliest clothes worn by man were the furs, skins and pelts of the animals they killed while out hunting for food. When hunting was such a dangerous, labour-intensive and time-consuming part of one’s day, absolutely any and every part of a dead animal was used for something. The flesh was eaten, the bones were used to make tools or equipment, and the pelts and skins were used for clothing, or making shelter. The first needles were made out of shards of animal-bone, and the first threads for sewing were the sinews and muscle-fibres taken from these dead animals.

Using rudimentary knives such as napped flints or chunks of razor-sharp obsidian (basically, volcanic glass, which is sharp enough to shave with!), primitive man learned how to skin, cut, and sew together animal pelts to make the first ever articles of clothing – likely loin-cloths (for the covering of one’s loins), or cloaks and capes, for covering one’s shoulders, chests, and backs.

Weaving, Knitting and Spinning: Wool, Wonderful Wool!

Finding enough mammoths, tigers, lions and other furry animals to kill and make clothing is obviously labour intensive and dangerous. The next step in finding ways to make clothing was to grow it! Instead of chasing the sources of your clothing, simply grow it, or let it come to you. Using the long strands and fibres in plants like flax, cotton and hemp, or the strands and fibres in the wool of sheep, mankind realised that if they could utilise these naturally occurring materials, they could make clothing. More clothing, better clothing, and more comfortable clothing! Thus began the domestication and farming of fat, fluffy, woolly sheep!

But, having sheep was not enough. To make fabric from the sheep’s wool, two innovations were necessary – that of spinning the fibres to make a thread, and that of weaving the threads to make cloth.

Unlike cotton and flax, which were seasonal and which were more affected by weather, the wool on sheep was a reliable and plentiful source of material. Because of this, for centuries, sheep’s wool was used to clothe people throughout Europe and North America (in South America, alpaca wool served the same purpose).

Using knives or basic clippers, mankind learned how to shear sheep, to remove as much of this wool as possible for the manufacturing of clothes. It is actually necessary to shear sheep – if you don’t, the wool builds up into unmanageable layers and the sheep can actually die from the weight, the heat, and the infestations of grubs and maggots that get into the wool…eugh.

Shearing and processing wool was a big undertaking. The first step was to wash the sheep. This was usually done by simply dumping the poor animal into a river. The fast-flowing water would blast out all the mud and gunk from the sheep’s woolly fleece, and then you simply trotted it back up onto shore, let it dry out, and then sheared it.

The next step was to shear the sheep, using knives or clippers. You had to get as close to the sheep’s skin without actually nicking it. If you did, tar, pitch or some other adhesive was usually applied to the wound to stop the sheep from getting infected. Sheep were extremely important in Europe, and great care was taken in their maintenance.

Once the wool was removed from the sheep, the next step was to card it.

Carding was the process of combing the wool and cleaning it. This was done by combing it over and over again between two drums or paddles with rows of hooks or needles set into them. The hooks grabbed the wool and stretched out the fibres, combing everything into one direction. This aligned the fibres, but also separated them. This allowed you to clean the wool – picking out any grubby bits that you didn’t want!

A classic, treadle-powered spinning-wheel from the 1600s and 1700s. Being able to sit down while spinning made the job far more comfortable and made production of spun threads and yarns far more efficient.

Once the wool had been carded and cleaned, it could then be spun. Spinning was what compacted and aligned the fibres of the wool, twisting it into a continuous yarn. This was traditionally done on a spinning-wheel, either a small wheel and spindle, at which you could sit and pedal for hours at a time, or at a so-called ‘great-wheel’, which was a huge iron wheel which was spun around continuously, stretching and twisting the fibres of wool that you fed in by hand, into a continuous yarn or thread.

Unsurprisingly, to get enough thread to make anything of significance, you needed to do a lot of spinning. Spinners would walk for miles and miles a day, pedaling or moving back and forth against the spinning of their wheels, to produce thread. As this task was often done by unmarried women with few prospects, the term for an unmarried woman became a ‘spinster’.

Weaving Wool

Once the threads had been spun, the next step was to weave it. This was either done by knitting – looping the wool back and forth against itself to make fabric – or by weaving it back and forth, up and down, using a weaving loom.

Weaving looms were impressive machines, requiring great concentration to both set up, and operate. As the size of the finished fabric was dictated by the size of the loom, some looms could be gigantic! Two rows of thread (the warp) were set up in the loom, moving up and down, alternating back and forth. Between these two rows of thread, the weaver passed a spindle of thread mounted on a boat-shaped device called a shuttle. The thread going back and forth was called the ‘weft’. Together, weft and warp, woven together, created cloth. It was important for thread-tension to be kept even, and for the weaver not to lose concentration, or else the finished fabric wouldn’t hold together…whoops!

For centuries, weaving was done by hand. The weaver operated the levers which shifted the warp up and down, with his or her feet, while their hands operated the shuttle of thread which ran back and forth. This was a slow, laborious task – but one which was highly skilled – it took a lot of concentration to set up the loom, and one mistake would affect the entire outcome of the finished cloth!

Finishing off Fabric!

Once the fabric was woven, and released from the loom, it then had to be finished. Freshly-woven fabric (especially wool) was rough and stiff. This was because of the fibres of wool, and the oils that they contained. To produce a fabric that you’d actually want to wear, the cloth had to be processed or finished-off, in a process called ‘fulling’.

Fulling involved breaking down the fibres of the cloth and cleaning out the oil and grit from the wool, making it softer and fluffier. Ooooh, fluffy!

For centuries, this was done through brute force, and the addition of…human urine.

Do you know anybody with the last name ‘Fuller’? Well, chances are that in the dim and distant past, their great-great-great-great-great…great-great-great…great-great…great ancestors…had the unenviable occupation of being a fuller! A fuller was the person who fulled (processed) cloth. And this was done by dumping the raw fabric into a vat, tub or barrel, and then soaking it in stale piss! The ammonia in the urine dissolved the grease and oil in the wool (produced by the sheep), making it softer and cleaner and easier to use. Once the fabric was drenched in piss, it was the job of the fuller (or if he was lucky, his hapless assistants, or even slaves) to tread the fabric. Constant treading, beating or pounding of the piss-soaked fabric closed up the fibres in the cloth, making it more homogeneous, removing all the little pinprick holes that were left by the weaving.

Once the cloth was softened and finished, it was removed from the piss-vat by the slaves or fuller-assistants (who probably had received a crude pedicure at the same time), then washed, and then strung up! Fabric (especially wool) crinkles up when it’s wet – making it of no use to anybody. To stretch out the fabric and remove any pesky elasticity from it, it had to be stretched out. To do this, it was held in place by small, bent iron hooks or nails.

Ever heard of the expression that someone is ‘on tenterhooks’?

This is where it comes from.

Fabric was literally stretched out on tenterhooks and kept under…tention…or…’tension’, as we’d say today – to remove the springiness from the fabric, to ensure that it didn’t crinkle up again like a ruffle-cut potato chip. Once the tension had been stretched out of the fabric, it was ready for use!

Clothes Throughout History

Once processes for finding fibres, refining them, spinning, and weaving them into fabric had been perfected, what came next was the actual process of making clothes – the results of which were typically dictated by time, price, climate, and of course – fashion!

The process of making clothes has not changed in hundreds of years. Panels of cloth, cut according to measurements, were sewn together with a needle and thread, resulting in a finished garment. What did change, however, was what those garments looked like, over the coming centuries, ranging wildly in colours, sizes, complexities, and fabrics. For a long time, clothing was seen as much more than just something to keep you warm and comfortable.

Clothing in the Middle Ages

We pick up on the saga of clothing in the Middle Ages. One event – one long, wavering event, would affect the clothing of the people of the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance, and the Early Modern era, all the way up to the time of the Victorians – and it’s important to know what this event was, to understand the evolution of clothing during this long stretch: An event called the Little Ice Age.

Stretching from about 1300-1850, the Little Ice Age was a weather phenomenon that came and went over the next half-millennium, cooling the earth gradually every couple of generations. This resulted in shorter summers, and longer, and colder winters. So cold, in fact, that major rivers in European cities such as the Thames in London, would freeze solid, right up into the 1840s and 50s, which is not that long ago!

But what affect did the Little Ice Age have on clothing?

Because of the decidedly harsher climate across Europe and America, China and Canada, during this time, clothing was by necessity – thick, and worn in layers. Cloaks, capes, shawls and wraps were common. Women wore layers of petticoats, skirts and bodices, while men wore thick, baggy shirts, woolen britches or leggings called hose, and a jacket or coat known as a ‘doublet’, so-called, because it was quite literally – double-lined in wool, inside-and-out, to provide warmth against the cold.

Clothes like this lasted virtually unchanged in their essentials, from the Middle Ages through to the 1700s.

Edward VI wearing a doublet and hose. This look remained common for men throughout the medieval era and renaissance, until the early 1600s.

While men wore leggings, hose, stockings, tunics (baggy, collarless shirts), with doublets and cloaks on top, women during this era covered themselves with a profusion of fabrics. The first garment was typically a chemise (a light, undergarment), followed by her corset (usually stiffened with wood, or whale-bone), followed by petticoats, skirts, a stomacher (a padded apron), and dozens of pins, all used to hold these various pieces of clothing together. Pins were so essential to dressing, in an age before buttons and zippers, that there was an entire industry devoted to making them, back in the 1500s.

In many respects, clothing like this changed little between the 1200s or 1300s, up to the dawn of the Modern Era, with the generally colder weather around the world meaning that it was just more practical to keep on wearing so many layers.

Clothes Maketh the Man

It was during this era that clothes were seen as a status-symbol. Given that they were so incredibly labour-intensive to produce, most people owned few clothes – at best, maybe two or three full sets each, generally just chopping, changing, darning, patching and sewing them up, over, and over, and over again, to keep them going as long as possible, before they could afford to buy enough fabric to make another set.

Because of this, for a long time, clothing – both the quantity and the quality of it – was a massive status-symbol around the world. Dresses, shirts, skirts and cloaks made of velvet, silk, or satin, instead of cotton or wool, were seen as more luxurious and higher-class.

People of Colour!

These days, we don’t think much about the colour of our clothing, beyond what colours go with which other colours. I mean you’re not gonna wear THAT…are you? Oh god…

But in times past, the colour of the cloth which made up your clothing was actually of great significance. Colours such as red, white, green, black and even purple, were considered highly fashionable and popular. This was partially due to their brightness or contrast, but also because of their expense. Purple, green and white were considered desirable because they were thought to display wealth, power and taste!

Purple in particular, was difficult to make, requiring a chemical reaction, in which crushed seashells were needed to dye the cloth. It was so expensive and labour-intensive to produce that for centuries, only royalty and nobility could wear cloth made of purple. Even today, royal cloaks and robes are a deep purple colour. That’s not an accident.

Red was also popular. A bright, scarlet red was traditionally produced by crushing tiny cochineal beetles. The dye in their shells could be used to stain the cloth red. Red was popular for dresses, cloaks, doublets, tunics…all kinds of things! In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, cochineal dye was most famously used as the red dye for the redcoat uniforms worn by British soldiers.

Diarist John Evelyn. In the 1600s and 1700s, crisp, white linen collars, cuffs and neckerchiefs were a sign of wealth, since it took so much money to buy such clean white cloth, and then so much effort to keep it clean and white!

Another highly popular colour was white – white cuffs, white collars, white ruffles, neckerchiefs, cravats, shirts and other flourishes and accessories were extremely popular in the 1500s, 1600s and 1700s. The more you had, the more affluent you were. This was because it suggested that, not only did you have the money to spend on such fine, crisp, white linen, but you also had the money to pay servants to keep it clean and white and crisp, sprinkling it with starch to help keep the shape and colour. Being trimmed in white also suggested that you were a man or woman of means – you had your own money, or at least, earned it through means of business and trade – not through such horrible occupations as farming or mining or doing manual labour, which might soil your beautiful white collars and cuffs with grime and dust and sweat!

It’s a huge misconception that people in the past did not care about colour in their clothing. They most certainly did, and they used it as a way to express their wealth and status. And not just in Europe. In China, yellow was only ever worn by the Emperor, red was worn for celebrations, and in Asia, just as it was in Europe – purple was the colour of royalty.

The Renaissance Man and Woman

By the 1400s, 1500s and 1600s, clothing was gradually becoming more refined. For men, separate leggings were now becoming a single garment. What were previously called ‘hose’ were now called breeches, or ‘britches’, knee-length coverings with a sort of drawstring opening at the front, similar to a modern fly. This was augmented with a pouch or flap of cloth known as a codpiece, with which to cover your ‘codware’.

For those who could afford it, clothes were now being made in a more tailored way – by the 1600s, it became common for men to wear long tailcoats, and long waistcoats to combat the cold winter air. Under this, they still wore their simple, white shirts, however. These shirts were long, baggy and typically made of linen or thin wool fabric. They were worn baggy because part of their function was to act as underwear, and as sleeping attire. At the end of the day, you removed all your coats, waistcoats, cloaks and jackets, and simply went to sleep in your shirt, or ‘nightshirt’ as it became known. This tradition persisted right up into the Victorian era, and even in the later 1800s, to be seen ‘in your shirtsleeves’ as it was called – was tantamount to walking around wearing a jockstrap and nothing else – a MAJOR social faux-pas for the time!

Capt. James Cook in his naval uniform, which consisted of knee-length breeches (buttoned at the thighs), and knee-length white stockings beneath.

For women, the layers of petticoats and skirts remained the norm, although by now, a new innovation which the woman who could afford it, might add to her attire was this newfangled ‘pocket’ thing that people kept talking about.

Pockets had existed before, but it wasn’t until the 1500s and 1600s that they really became a thing. In previous times, a ‘pocket’ was a simple pouch strapped to your belt, and was also called a purse. But these pockets – made in pairs – with tie-strings on them, could be tied to a lady’s undergarments, hidden away from view, in which she might keep her money, scissors, spectacles, or anything else that might fit inside.

Of course, if the straps which tied the pockets to your skirts came loose, then you would literally – lose a pocket…like Lucy Locket…which is the origin of the nursery rhyme.

As I said before, during this time, your clothing was a serious marker of your social and financial status. If you walked around town in your fine dresses, long, flowing, embroidered coats and jackets, or crisp, white linens, you would really stand out as a member of the upper-clasess…which meant you had money…lots of money! Which meant that you could probably stand to lose some, yeah?

Well, others certainly thought so. It was at this time that we are introduced to the character of the ‘cutpurse’, a person who would wander around behind unsuspecting toffs, and quite literally use a small knife to cut the drawstrings on their purses or pockets, catch them before they hit the ground, and then run off with them, without the owner being any the wiser! In time, the cutpurse would attain a new moniker – the pickpocket!

The Start of the Suit

In modern English, a ‘suit of clothes’ is a set of clothing all cut from the same cloth. As we’ve seen, clothing in the past was not. Shirts, jackets, waistcoats, breeches, leggings, petticoats, chemises, dresses and cloaks were made of a wide variety of fabrics – cotton, wool, tweed, silk, satin…the list goes on.

So, when did the suit as we know it – a set of clothing all cut and made from the same type and colour of fabric – first originate?

The suit as we know it is comprised of three components: The jacket, the trousers (a two-piece suit), and a waistcoat (three-piece suit). How far back does this combination, in matching fabrics – go?

The immediate ancestor of the suit dates back to the 1600s. This was when men started wearing breeches instead of separate leggings which were simply tied to their shirts. Originally called hose, breeches were knee-length coverings comprised of a seat, front, fly, and two legs. Indeed, during the 1500s and 1600s, and even into the 1700s, a rite-of-passage for small boys was the transition from wearing baby-clothes (typically dresses or skirts), into wearing breeches (the forerunner to trousers), and it was considered a major point in their lives, since indicated that they were growing up.

Why, you might ask, did little boys wear skirts as toddlers, instead of breeches? Well, it’s a lot easier to clean up a toddler’s bodily motions when they’re wearing skirts. The transition to breeches indicated that they had grown up enough, and were now mature enough, to handle their bodily functions on their own, and were therefore mature enough to wear breeches. This rite of passage was known as ‘breeching’. In one form or another, it remained common into the 20th century. But more about that later…

The Jacket

The first part of the suit is the jacket. Men had been wearing jackets or coats for centuries, and by the 1600s, the long tailcoat with cuffs and pockets with flaps had become an established article of men’s clothing. They varied in length, but at their most extreme, went down to below the knee for winter garments, and around thigh-level for warmer-weather jackets.

The Breeches

As mentioned, breeches descended from hose, which descended from the separate leggings worn in Medieval times. By the 1600s, breeches had become an established part of European menswear, usually matched with a pair of knee-length stockings, typically white, although other stocking-colours were also popular. By this time, pockets, at least for men, started becoming ‘in-built’ into their garments. No-longer were they little sacks or pouches that hung off the side on strings. Now, they were being sewn into, and onto, men’s clothing, such as the pockets in coats and waistcoats, so did early trousers and breeches also have pockets.

Breeches remained popular from the 1600s up to the early 1800s, due to the fact that most men either walked, or rode a horse everywhere, to get from place to place. The poor condition of roads meant that it was highly likely you’d get splattered with mud, rainwater or dust while out riding or walking, or even just getting in and out of your carriage. If your stockings got wet or muddy, you could simply change them, and keep wearing the same pair of breeches for a longer period of time before they too, would have to be washed (in a time when washing clothing was an extremely laborious task, garments were, of necessity, washed as infrequently as possible to save on water, fuelwood, and expensive soap, a commodity which remained taxed in England right up to the Victorian era). Wearing knee-length breeches, which were less likely to be soiled by grime, and a pair of removable stockings, was therefore seen as a matter of practicality, as well as fashion.

The Waistcoat

Arguably, the first instance of a ‘vest’ or ‘waistcoat’ being mentioned in the English language is in Samuel Pepys’ diary of the 1660s, when he describes King Charles II of England, wearing such a garment, and declaring that his courtiers should do the same. Early waistcoats, much like the jackets and coats of the era, were dictated by the ‘Little Ice Age’ at the time. Waistcoats were much longer than modern ones, reaching as far down as the knee in an effort to provide warmth and deal with drafts.

The beginnings of a Suit

With these three components: A coat or jacket, vest or waistcoat, and a pair of breeches with stockings, the suit as we would know it today, was in its infancy. Over time, it would gradually evolve. By the 1700s, the waistcoat would shorten in length and coats and jackets would become less elaborate. The fashion for breeches remained for much of this time, though, due to reasons explained previously. It would not be until the early 1800s that they finally started to be usurped by trousers.

Dandies, Fops and Macaronis

By the 1700s, men’s and women’s daily attire had hardly changed markedly from what it had been a hundred, or even two or three hundred years before. For women, layers of petticoats, shawls and undergarments remained the norm. For men, things had advanced somewhat, but the layers of clothing and elaborate attire remained de-rigeur. Jackets and waistcoats had increased or decreased in length according to fashion and style, and by the Georgian era, it was slowly becoming less and less elaborate…although that is a matter of opinion, in some circles!

Foppish Macaronis!

“Now Sir! You’re a complete Macaroni!” – The over-the-top outfits worn by men in the late 1600s and 1700s were what gave them the nickname of ‘fops’, ‘poppinjays’, or ‘Macaronis’. This dependence on powder, rouge, scent and bright colours was seen by some as being overly effeminate.

By the 1600s, a phenomenon known as the ‘fop’ had arrived on the scene, also called a ‘poppinjay’ or even a ‘coxcomb’…these were all derogatory terms coined to describe the sort of excessively well-dressed, superficial man, typically of wealth or breeding, who spent far too much time concerned with his clothing, makeup, scent, and general appearance in public! These last two terms – poppinjay and coxcomb, aimed to compare the fop with common birds – specifically the parrot, and the rooster (or ‘cockerel’).

Why?

Because, like a rooster or some other exceptionally flamboyant and flowery bird – they were constantly strutting around, heads up, making loads of noise, trying to get others to notice them, while also preening themselves endlessly, with scent, perfume, powder and makeup! Bedecked with jewels, brocade suits, ruffs, frills, overpowering cologne, insanely elaborate wigs dusted over with powder to give them a brilliant, bright whiteness, fops embodied the 17th and 18th century man of means.

Linked closely to the fop was the equally dazzling ‘macaroni’, as in that old nursery rhyme of Yankee Doodle and his hat with the feather in it.

Calling it ‘Macaroni’!

By the 1700s, it became increasingly popular for young men to do what was called the ‘Grand Tour‘ – basically a sort of 18th century gap-year. The idea was that – if you could afford it – you packed up your trunks and bags, and, with a companion, friend or tutor, went off on a tour of Europe – generally encompassing France, Germany, the Netherlands and the Italian City States. This was supposed to be a mind-broadening exercise – to expose clueless young English noblemen to the refinement, style, class, and fashions of the continent!

Having been exposed to all this grandeur and fashion, it was expected that these feckless young toffs would have returned from their travels with a more cultured, sophisticated outlook on life, having learned about the classical societies of Greece and Rome, perhaps learned a foreign language, or developed a greater appreciation for the arts. One thing which these young men developed a taste for was Italian cuisine…you know…pasta. Specifically – this newfangled ‘macaroni’ thing, which most people had never seen before!

Macaroni then became a term used to describe young, clueless men of questionable cultural understanding, who were determined to copy or imitate high European fashion and society. As with anything when people try to imitate the styles, fashions, cuisine or culture of a foreign nation, things get lost, exaggerated, or simply left out, of the translation – and this caused the Macaroni faddists to become ridiculed by their peers.

Fine and Dandy

As you can imagine, all this excess started to get rather…excessive. Especially by the end of the 1700s. This led some to seek a simpler, cleaner, more refined look. Spearheading this new, clean-cut look was George Brummell – better known as ‘Beau’ Brummell. Well-educated and from a decent, middle-class family, Brummell had spent time in the army where he became friends with the Prince of Wales (later the Prince Regent, later George IV).

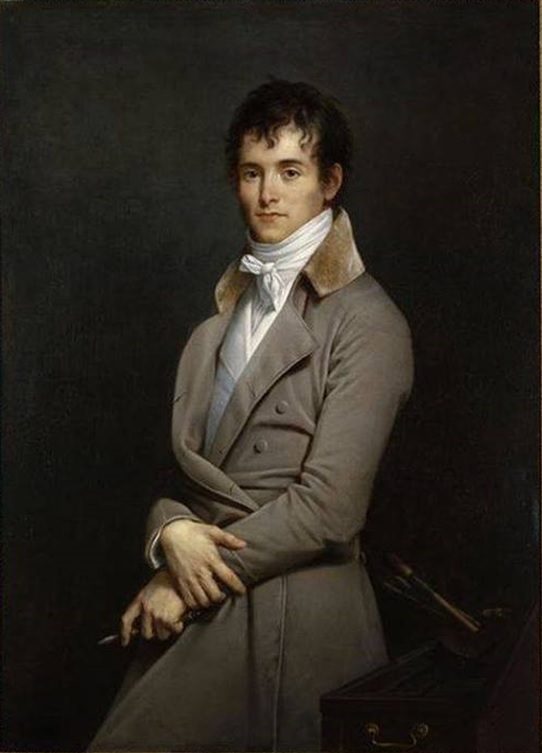

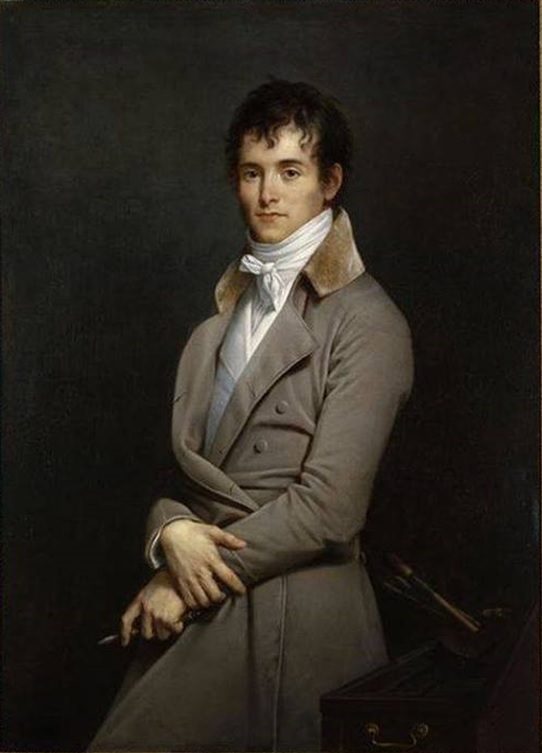

Rejecting the powder, wigs, scent, makeup, love-spots and other trivialities of the fop, Brummell strove to create a cleaner, simpler look for the man about town. Instead of breeches, he introduced trousers. Instead of bright, flashy, garish colours, he insisted on darker tones. Navy blue. Black. Grey. He contrasted this with crisp, white linen in the form of shirts, and crisp, white neckerchiefs and cravats – the immediate predecessor to the modern necktie. Brummell was such a perfectionist with his wardrobe, it’s said he took up to five hours to get dressed, and required the aide of his manservant to do such things as tying his cravat.

The Dandy Movement, started by Brummell, spread around Europe in the late 1700s and throughout the later Georgian era of the 1810s, 20s, and 30s. This portrait was painted in France in 1801. The cleaner, simpler lines and less flamboyant colours display a complete departure from the loud, garish outfits of the macaronis and fops, just a few decades before.

The simple, elegant look popularised by Brummell started being copied throughout Europe and North America, spreading around the world with European trade and colonisation. It was easier to tailor, and less elaborate. On top of that, the dandy also presented himself differently to the world: No wigs, no powder, rogue, no makeup of any kind, beyond maybe the occasional spritz of cologne. They kept themselves washed, cleaned and close-shaved and insisted on their clothes being carefully laundered. Brummell himself insisted on polishing his boots with champagne!

Victorian Vanity

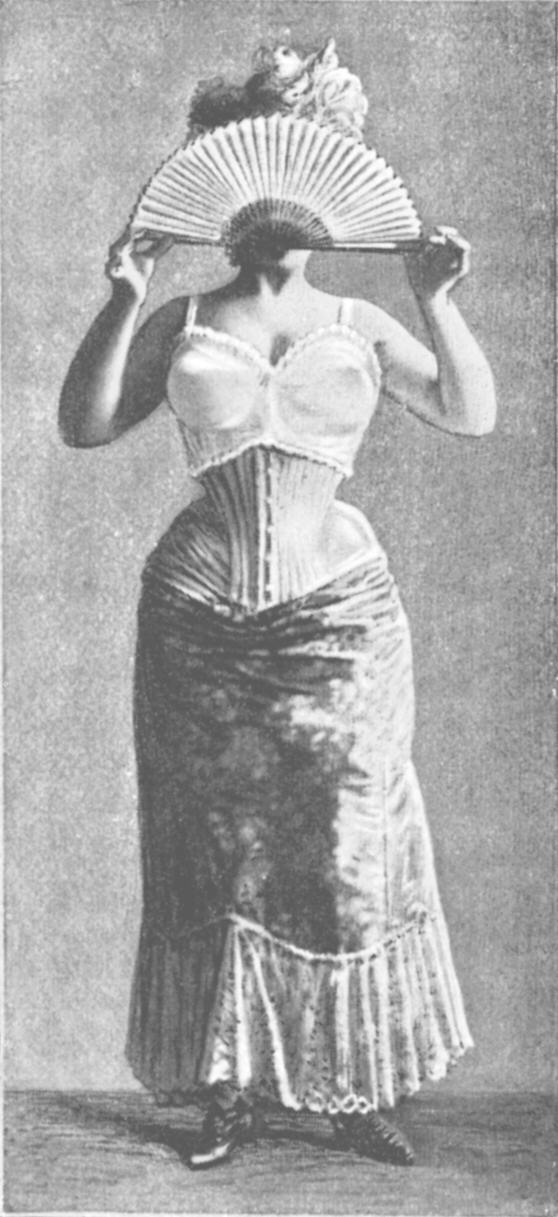

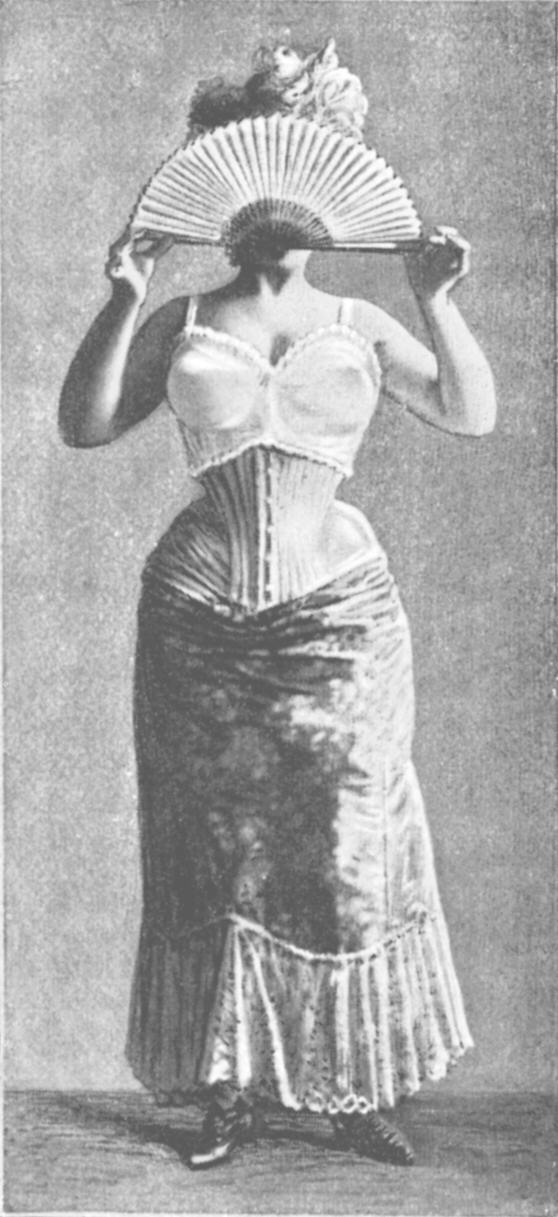

By the Victorian era in the 1830s, 40s and 50s, men’s and women’s clothing was becoming less elaborate, and more clean-cut and simplified. Excessive use of colour and flashy fabrics was no longer seen as fashionable and things like frilly collars and cuffs, elaborate ruffs and heavy embroidery started to disappear, to be replaced by a simpler, cleaner look of white collars and cuffs, simpler, solid colour dresses and suits, and an overall more sedate form of dressing. For women, the desire for a curvy, hourglass look led to the agonising fad known as ‘tight-lacing‘, where women would literally be crushed into the tightest-laced corsets that they could possibly stand, and which were tied up phenomenally tight so as to help maintain their figures.

For women, corsets had been a thing for centuries (even some men wore them!), but tight-lacing was corsetry taken to a whole new extreme. Women being unable to eat very much of anything, having having their ribcages deformed, and even fainting from the inability to breathe properly became commonplace, and fainting-couches, fans and phials of smelling-salts were required to combat these fainting-spells. For a long time, Victorian-era policemen would carry, as part of their standard-issue equipment – a bottle of smelling-salts (called a ‘lady-reviver’), to bring consciousness to any fainting females falling in the streets.

For men, by the 1800s, the combination of stockings, breeches, long flashy cloaks, coats and waistcoats were seen as excessive and tasteless, and were replaced by simpler, and more conservative suits, paired with trousers. Gradually the shirt, once considered an unsightly undergarment, also started rising in status.

The Shifting Shirt

Although in Victorian times, it was still considered crude and unsightly to appear in public in your shirtsleeves, shirts themselves went through a bit of an image-improvement campaign. Proper dress-shirts, similar to the kind we know today, started being developed. These had no collars, very long sleeves, and long shirttails and were known as ‘tunic shirts’. They were cheap, mass-produced and could be worn by almost any level of man in society.

Because early manufactured shirts were of a ‘one-size-fits-all’ variety for the most part – the sleeves were often quite long. To adjust the sleeves to your length, you rolled or pushed them up at the elbow, and wore a pair of ‘sleeve-garters’ to hold back the excess fabric, so that the cuffs rested at your wrists in the right position. Sleeve-garters are those elastic-band thingies that you see barbershop quartets wearing on their sleeves.

Ebeneezer Scrooge from Dickens’ ‘A Christmas Carol’, in his long, flowing white night-shirt.

During the Victorian era, the shirt was seen less and less as a sleeping garment. The concept of the ‘nightshirt’ started to fade away, and break off into a separate entity, to be replaced by dressing-gowns and pajamas, since people suddenly decided that maybe it would be more comfortable to sleep in silk, satin and soft woolens, rather than in a shirt that you’d been wearing all day long…possibly for several days straight!

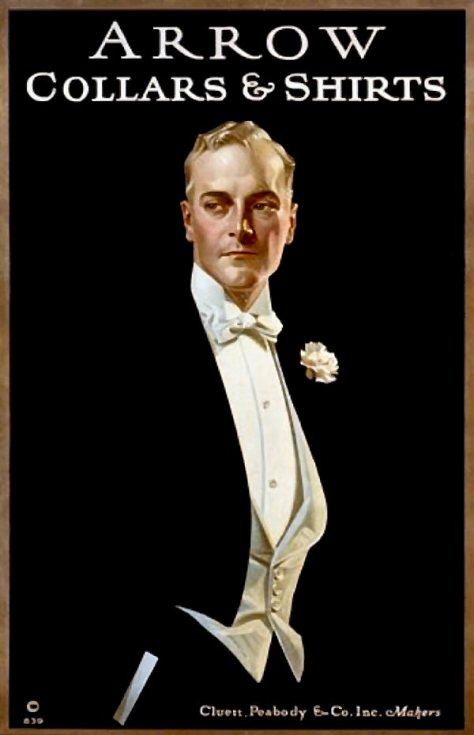

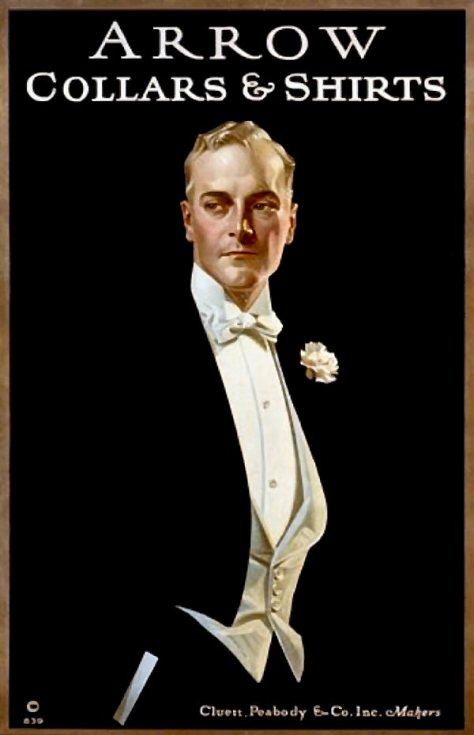

In the early 20th century, shirts and collars were still sold separately. ‘Arrow’ collars were particularly popular – even appearing in the 1929 song ‘Puttin’ on the Ritz’ (“…high hats, and Arrow collars, white spats, and lots of dollars…”)

One peculiarity of shirts, right up to the early 20th century, was that they had no collars! Shirt-collars, and even shirt-cuffs, were detachable, removable, and could be (and were) cleaned separately from the shirt itself. This was because the shirt was still seen as underwear, and washing shirts was expensive, what with the price of soap, coal or wood for the hot water, and the sheer time and effort involved in laundering. You would wear your shirt as long as possible (up to a week or more in some cases), and you only changed the collar and cuffs (held on with studs or buttons) with any regularity, finally changing out the shirt at the end of the week. One benefit of this style of shirt was that you could chop and change your collars as you saw fit. Arrow-point, wing-collars, Eton-collars, rounded collars…the variations you could attach to your shirt were pretty extensive! Shirts with attached collars and cuffs wouldn’t become a thing until after the First World War.

Waisted Shirts!

By the 1800s, clothing for women also began to change. Instead of clumsy bodices, women in the 1800s could look forward to the forerunner to the modern blouse – called a shirtwaist. Made out of cotton shirt-fabric (hence the name), the shirtwaist was basically the female version of the men’s shirt, but with included collars and cuffs, which were sewn, rather than buttoned, on. Shirtwaists remained popular throughout the Victorian era, and extended into the early 20th century.

As the 1800s continued, dresses for women also started to get simpler. Outrageously wide crinoline skirts, and bulky, ludicrous bustle skits gave way to simpler, more flowing designs which ere not only more comfortable, but also far more practical. This was followed, in the second half of the 1800s, by the Victorian ‘Rational Dress Movement’, which encouraged women to cast off the bulky, overladen outfits of their parents and grandparents, and to take on simpler, more comfortable, and sensible clothing styles that made moving, eating, breathing and dressing, much more easy, and also, much more comfortable!

The Rational Dress Movement

The Rational Dress Movement is something most people have probably never heard of, and yet in its day, it was a revolution.

By the mid-1800s, the growing Industrial Revolution was affecting everybody’s lives. Even the lives of women! For the first time, it was possible for women to enter the professional workforce. They became nurses, pharmacists, schoolteachers, nannies, governesses, and dressmakers. No longer chained to the stove and shackled to the broom, women in work decided that they needed more practical, and comfortable clothing. Crinoline dresses and enormous bustles were impractical for serving customers behind a shop-counter, serving diners tea, crumpets, cakes and sandwiches, or tending to the sick in hospitals.

Bloomers and similar, less baggy outfits allowed women to take part in sports and activities such as cycling, which were impossible in the bulkier layers of skirts that they used to have to wear. This advertisement is from 1897.

Because of this, by the 1850s, 60s and 70s, a growing number of women, who would later give rise to the suffragette movements of the 1890s and the early 20th century, decided that a fullscale reform of women’s clothing was necessary! Away with the ridiculous layers and layers of skirts and petticoats and stomachers and bodices! Throw out your hoop skirts and hobbles, your bustles and braces! Instead, from now on, women’s clothing was going to look to comfort, ease of movement, and simplicity to be its guides, rather than frivolous use of fabrics and layers!

Skirts and dresses became simpler, less flamboyant and ostentatious. Ladies’ undergarments became less bulky, and were replaced by bloomers – baggy, divided garments which when together, looked like a full skirt, but which parted in the middle to allow for greater movement. The arrival of the bicycle in the 1880s meant that women could, with their new clothing – actually travel long distances in relative speed and safety – without needing to be accompanied by someone to manage the horses!

The Rise of the Sewing Machine!

You could hardly talk about a history of clothing without the impact of the sewing machine.

Although the first sewing machines were invented in the 1700s, it wasn’t until the mid-1800s that enough people with enough money and enough individual ideas and patents, had discovered enough to build a really, properly-functioning sewing machine. The man who did this was a German-American, named Isaac Merritt Singer.

You…might possibly have heard of him.

Singer did not ‘invent’ the sewing machine, as much as he just stitched it together. He did this by stealing all the ideas from all the other people who had claimed to have had ‘invented’ the sewing machine – and then putting all these different patents together into ONE machine!

Unsurprisingly, all these other guys started trying to sue him, but Singer came up with another idea – Since no one person could make a functioning sewing machine without patents from the other parties involved – they should pool their patents to make sewing machines – and then sue anybody else who tried to copy them!

The other sewing-machine pioneers decided that this was such a fantastic idea that they agreed almost at once, and drafted up a document which created a body known as the Sewing Machine Combination – because it took the combined efforts of all these patent-holders to make a functional sewing machine.

From the 1850s onwards, the sewing machine sped up the production of clothing enormously – what took a seamstress, tailor, dressmaker or shirtmaker half a day to produce, could now be done in a matter of an hour or two, and to a much higher standard of quality. For the first time in history, mass-produced clothing was possible. Shirts, undergarments, jackets, trousers, blouses, skirts, dresses and other articles of clothing could be produced cheaply and efficiently.

Sewing machines were expensive in their day – companies like Singer, Wertheim, New Home, Jones, Wheeler & Wilson, and countless others – typically sold their machines through hire-purchase schemes, since it was almost impossible to buy a machine outright due to the high prices. The sewing machine allowed men and women who made their livings from the clothing trade to vastly increase their output and improve the quality of their wares. A house with a sewing machine, and a person who knew how to use it, would have at least some sort of income even if the main breadwinner had lost his job, because the machine virtually paid for itself.

Hand-cranked vibrating-shuttle sewing machine, typical of those manufactured and sold during the late 1800s. Made by the Wertheim Sewing Machine Company, ca. 1910.

From the 1850s up to the 1960s, the vast majority of sewing machines were black, cast-iron monsters mounted on wooden bases. Many were heavily decorated with gold decals, brightly painted patterns and decorations, and even mother-of-pearl inlays. Since they were so expensive, sewing-machine companies wanted their machines to look as attractive as possible so that people would feel that they were worth the outlay.

Clothes for a New Century!

By the early 1900s, clothing was changing faster than ever. By now, things like jeans had been developed (in America in the 1850s), as well as cardigans (England, 1850s), and we’ll round off our look at clothing through history, by looking at two staples of the modern wardrobe: T-shirts, and bras.

The Terrific T-Shirt!

The T-shirt, an article of clothing so common today that anyone reading this posting probably has a dozen of them in their closet right now – was first conceived of back in the 1800s – a time when all shirts in general, were considered as unsightly undergarments, not fit to be seen by the eyes of man – and definitely not by the eyes of women! The T-shirt was an undergarment, descending from the one-piece ‘union-suit’ cold-weather underclothes worn during the late 1800s. These eventually split into two separate garments – the top of the union-suit became a T-shirt, with shorter sleeves, and the bottom became long-johns.

T-shirts became popular in the early 1900s, when they were used as undershirts by factory-workers, sailors and soldiers – spreading widely in popularity during the period of the First World War. By the end of the war, the word ‘T-shirt’ had officially entered the dictionary.

A sailor wearing a T-shirt in the U.S. Navy during the Second World War.

T-shirts exploded in popularity in the 1920s and 30s – cheap and easy to manufacture, they were worn by men and boys looking for a lightweight, comfortable upper garment. Initially, their popularity was largely restricted to the army and navy where they had been widely used back in the 1910s, but with the coming of the Second World War, the T-shirt began to spread. Sailors in the US Navy stationed in the Pacific started wearing T-shirts (originally an undergarment) as outer garments while on deployment, due to the tropical heat. This trend carried over into their postwar-lives, and in the late 40s and during the 1950s, the T-shirt increasingly began to be seen as being a flexible garment, suitable for both underwear and outerwear, depending on the weather.

By the end of the 1950s, the T-shirt had become an accepted article of menswear and children’s wear for boys, replacing things like button-down sleeved and collared shirts, which were more expensive to produce, and which were less comfortable in warm weather. As time went on, the T-shirt became seen as a unisex garment, worn by men, women, boys and girls as a casual, easily-washed, cheap garment which could come in a wide variety of colours and designs.

The Beautiful Bra!

For centuries, women have needed to deal with a little problem…up top. And for a long time, to deal with this, they used everything from strips of cloth wrapped around the chest (‘breast bands’), to corsets, braced with everything from wood to whale-bone to steel! These were effective, but could also get pretty uncomfortable. However, by the end of the 19th century – something new came on the scene. From 1899, the first ‘brassiere’ became available! Invented in Germany by Christine Hardt, the Brassiere remained a niche item for over a decade, before mass production of the new undergarment began just before the First World War.

But, in a time when every woman alive would’ve known nothing but the restriction of a corset, what made the bra suddenly kick off?

Actually – we have the First World War itself, to thank for that.

Remember how I said that the corset went from wood, to whale-bone, to steel?

An early bra, worn over a corset, from ca. 1900.

I wasn’t kidding about that steel. By the Victorian era, corsets used LOTS of steel. Steel eyelets for the drawstrings, steel stays to provide reinforcement, and steel wire to help corsets hold their shape. Now, imagine that every single woman in Britain, America, Canada, France, Australia…etc…etc…etc…is wearing one of these steel-reinforced corsets.

That’s a LOT of steel.

A lot of steel, which could be used for making tanks…planes…rifles…field-cannons…

Basically, the bra was introduced just before, and during the First World War, as a steel-saving measure. Bras needed hardly any metal at all, whereas corsets needed loads! Women were encouraged to cast off their corsets and embrace bras! Women everywhere were gradually convinced that it was their patriotic duty to upgrade their underwear, and save steel for the war-effort! Huzzah!

By the end of the First World War, the bra had become an accepted garment of women’s clothing. It was gradually improved in the years that followed, with refinements in design, shape and support introduced in the 1920s and lettered cup-sizes coming in by the 1930s.

Closing the Lid on Clothing

Well, this ends our brief look at the history of clothing, and its evolution from the ruffs, doublet and hose, the bodice, corset and stays, to the arrival of jeans, T-shirts, bras, which, at the turn of the 20th century, heralded the coming of the modern wardrobe!

My grandmother’s sewing-machine, a Singer model 99k, made in 1950, in Kilbowie, Scotland

My grandmother’s sewing-machine, a Singer model 99k, made in 1950, in Kilbowie, Scotland