In this modern world of ours, with GPS, satellites, radio, live weather-mapping, and global communications, travelling anywhere – by car, by bicycle, by airplane, by ship – is pretty routine. We expect to board our vehicle, make ourselves comfortable, and arrive in our destinations…eventually. But for centuries, travelling across the world’s oceans was fraught with all kinds of dangers. Storms, hurricanes, rocks, reefs, pirates, illness, disease, rogue waves, navigational errors and the very real risk of getting hopelessly lost, to the extent that you couldn’t possibly find your way back home again.

This all began to change in the 1700s, when for the first time in history – mankind developed reliable methods, and instruments, for accurate, and safe, navigation at sea, beyond sight of land. Inventions such as the refracting telescope, the octant, the sextant, and the marine chronometer or ship’s clock, allowed sailors and navigators for the first time, to confidently sail beyond sight of land, cross an ocean, and confidently sail back again.

But there was a problem.

Sailing in the 1700s and 1800s was done by what was called ‘Line-of-Sight’ navigation. That meant taking visual references of what you could see of the world around you, to figure out where you were. For example, to find out your latitude, you measured the angle of the sun at noon, against the horizon to determine how far north or south of the equator you were. Similarly, you checked the time on your ship’s clock at noon, to determine the time-difference between local time (noon, indicated by the sun) and your port of departure (the clock) to calculate distance traveled.

The same thing applied when sailors got closer to land. Now you might think that this was easy – but in many ways it wasn’t. Sure, seeing land is great, but navigating along its coastline is not. Especially in bad weather, or at night, or when it’s cloudy, or excessively windy, or if the waves are too high…you get the picture.

Sailing ships are slow-moving vessels, and were equally slow to respond. If you were sailing along the coast and spotted trouble – you first had to consider yourself very lucky – since not all trouble could be spotted with the naked eye, or even the aid of a telescope – but secondly – you had to move very fast in order to maneuver your ship out of the way – not an easy task when it relies on the wind and currents to provide its motion.

This brings us to the one navigational aid which for centuries, has guided sailors in and out of harbours, and safely from shore to shore – an unblinking, unflinching guide, and a metaphor for hope against a sea of troubles.

The humble…

…lighthouse.

What IS a Lighthouse?

A lighthouse, as most people are doubtless aware – is a navigational aid in the form of a fixed point of illumination raised inside a tower to guide ships at night, or to warn them of dangers which may exist where the lighthouse was constructed (or nearby). For centuries they were so important that thousands of them were built all around the world lining coastlines, inlets, harbours, inland seas and lakes, as well as important navigable waterways such as estuaries, rivers and bays.

How old are Lighthouses?

If we accept that the term ‘lighthouse’ refers to a fixed point of illumination which serves as a navigational aid for shipping – lighthouses probably date back to antiquity – certainly to the time of Ancient Rome, and the fabled Lighthouse of Alexandria, in Egypt.

The fabled Lighthouse of Alexandria – a digital reconstruction, based on available archaeological evidence.

But if we accept that the lighthouse is a functional structure – a building specifically raised for the purpose of being a navigational aid, with a light inside it and someone to tend to that light, then how far back can we trace their development?

The Tower of Hercules, in Spain. Raised by the Ancient Romans in the 100s, the tower was renovated in the 18th century, and remains in use today as a navigational aid.

Most sources would say the 1600s. Or more specifically, the end of the 1600s.

“Why?” you might ask.

Simply because by the 1680s and 1690s, overseas traffic was increasing greatly. The end of conflicts in Europe such as the Anglo-Dutch Wars meant that there were suddenly loads of sailors sitting around with nothing to do. Some turned to piracy, while others tried to put their seamanship to good use, becoming merchantmen who sailed the high seas doing trade with Europe, the Med, and the American colonies of European powers. The uptick in oceangoing traffic meant that for the first time in a long time, a proper system of lighthouses was necessary to ensure that ships and their valuable cargoes were guided safely back to their home ports.

The First Lighthouses

The first lighthouses, mostly built in the 1690s and during the 1700s, were simple wooden towers raised on clifftops, rocky outcrops or islands off the coasts near shipping hazards like rocks or coral-reefs, or near the mouths of harbours. Their lanterns were little more than candles protected by glass. These early lighthouses were primitive, and were not strong enough to survive for any serious lengths of time. Wooden beams, no matter how securely-anchored or ingeniously dovetailed, could not withstand the force of Atlantic gales, pounding waves or the effects of nonstop dousing by a limitless amount of seawater.

Built by Henry Winstanley in the 1690s, the first Eddystone Lighthouse was a simple, wooden tower which was destroyed in a storm in 1703.

And on top of that – they were made of wood – not the best material for building a structure designed to hold a light, when the only lights available at the time were naked flames. After various early lighthouses either collapsed, were swept away, or got burned down, architects in the 1700s started looking for better designs and more robust materials with which to build them from.

The First Modern Lighthouse: Smeaton’s Tower

The first really successful lighthouse was raised in the 1750s, by architect John Smeaton, on the Eddystone Rocks off the southern coast of England near Cornwall. This replaced two wooden lighthouses built in previous decades, neither of which lasted for any great length of time. Learning from their mistakes, Smeaton looked for inspiration for his new lighthouse in nature.

The old lighthouses had been built of wood – weak – easily rotten – susceptible to both fire and water – hardly an ideal material. So the first change he proposed was to build the new lighthouse in stone. But this would prove useless if he couldn’t get the shape right, since the lighthouse would have to withstand the powerful storms of the North Atlantic, and the English Channel. While wood itself was unsuitable as a building material, it nonetheless served as Smeaton’s inspiration – large trees, which produced the kind of wood used in lighthouses at the time – were very tall – but also thick and broad at the base, with deep roots.

Why should his lighthouse not follow this model?

Smeaton decided that for his lighthouse to survive, it would have to be well-anchored into the rocks which he hoped his beacon would warn against. It would have to have a broad, deep base, with a sharp, upward curve from the ground, on top of which the tower would be built. This would serve to direct the force of any wave hitting the tower from the horizontal, to the vertical, where it would lose all its energy, posing no structural threat to the building.

Smeaton’s Tower. Raised in the 1750s, this lighthouse off the coast of Cornwall is widely considered the first modern lighthouse built with a specific design in mind.

To stop the tower from being blasted apart by the waves like previous, wooden structures had been, Smeaton had the stone blocks (granite) carved so that they dovetailed into each other, locking together like pieces of a puzzle. For extra strength, holes were drilled through the blocks and were further reinforced with rods of marble serving as dowels to stop the stones from splitting apart.

Apart from the stone lighthouses built by the Romans, the Eddystone Lighthouse or Smeaton’s Tower, as it became known, was the first really modern lighthouse to last any decent length of time. From the date of its opening (1759), it remained in continuous operation for over a century, until it was demolished, and replaced by the fourth (and current) Eddystone lighthouse, in 1877.

The Different Types of Lighthouses

Since the beginning, there were always two main types of lighthouses. Either cliffside or island lighthouses, with million-dollar beachfront views, or isolated lighthouses, built on rocky outcrops offshore, or even out in the middle of nowhere! Shore-based lighthouses were the easiest to build, and could become quite elaborate. Lighthouses built out on the open sea on the other hand, needed to be simple, but sturdy. In many cases there simply wasn’t the money, the time, or the space, to build anything more than the tower which held the light itself, and two or three rooms for the keeper and all his necessary supplies and worldly goods, to be housed in.

Shore-Based Lighthouses

Lighthouses built on land near the coast were typically constructed near harbours, fishing or coastal communities, or close to offshore shipping-hazards, to guide sailors along the coast and to warn them of the dangers lurking nearby. Since space was not a problem, shore-based lighthouses could be quite elaborate. Depending on the design and the land and funds available, the lighthouse would be used solely as a beacon tower, with storage inside for equipment, tools and supplies. The lighthouse keeper, and possibly his family as well, would live in the lighthouse keeper’s cottage next door. Boundary walls around the lighthouse-keeper’s property would protect both his dwelling and the lighthouse from waves nearby. Lighthouse keepers and their families would’ve been familiar as members of the local community.

Offshore Lighthouses

Being a lighthouse keeper could be a dangerous, lonely and exhausting job – no moreso than when you were the keeper of a lighthouse in the middle of nowhere! Many lighthouses off the coastlines of England, Ireland, Scotland, the United States, Australia and elsewhere around the world where there were large maritime communities, were manned by keepers who had the unenviable task of tending to a lighthouse from which they could not escape. Many were cooped up in them for weeks or even months on end.

Since they were built out in the open, offshore lighthouses had to be constructed much more differently than land-based ones. They had to be taller, their foundations deeper, their bases had to be shaped in specific ways to absorb the shock of waves, and the space inside had to be very carefully utilised. Unlike a shore station, a lighthouse in the open sea had to contain everything that it might need and be self-sufficient for weeks on end.

In a lighthouse built out in the open sea, space had to be used carefully. The keepers usually only had one or two rooms to themselves for eating, sleeping and activities. The other rooms would’ve been used for storing things like rope, wicks, cleaning materials, food, equipment, lamp-oil, and spares of things required to keep the lighthouse functional.

The Anatomy of a Lighthouse

Regardless of where they were built – all lighthouses had some things in common. The first thing was of course – the light, or ‘lantern’. This was housed in the ‘lantern room’, at the top of the lighthouse, protected by glass windows all around. Another feature of almost all lighthouses was the ‘gallery’, the circular balcony that wrapped around the outside of the lantern room. This allowed lighthouse keepers to maintain the windows and structure of the lantern room in a relatively safe environment.

In some places, a bell or horn was also mounted out on the gallery, and was used to indicate the presence of the lighthouse when it was shrouded in heavy fog, and the light could not easily be seen. The gallery also served as a convenient and safe platform from which the keeper could observe (and possibly, communicate with) passing ships, to warn them of danger. In lighthouses which were out in the middle of the sea, their greater height was used to create extra rooms inside the lighthouse which would be used for storage of long-term supplies like food, rope, wood, lamp-oil, wicks and tools. On shore-based lighthouses, these necessities could be stored in the keeper’s separate quarters or storage-buildings, leaving the lighthouse itself relatively uncluttered.

Lighthouse Development

As the 18th century morphed into the 19th century, lighthouses started becoming more and more sophisticated. Dovetailed stone construction, as pioneered by men like Smeaton, and Robert Stevenson, the famous Scottish engineer, became THE way to build sturdy lighthouses. Stevenson proved this beyond doubt when he raised the famous Bell Rock lighthouse off the coast of Scotland in the early 1800s. Taking years to build, the lighthouse had survived everything that Mother Nature could hurl at it, and despite being well over two hundred years old…the Bell Rock lighthouse remains operational to this day.

Lighting the Way: Beacon Development

But it wasn’t just in terms of construction that lighthouses were changing. They also changed in terms of the lights which they housed. Early lighthouses used candles, or crude oil lamps. By the late Georgian era of the 1800s and 1810s, more effective Argand-style lamps were being used. These lamps had a cylindrical glass tube, or ‘chimney’ placed over and around the flame. The chimney – like the chimney in a fireplace – drew the hot air created by the lamplight, up the shaft, drawing oxygen with it. This current of air fed the flame, which now would burn brighter than it would’ve done without the chimney. Combined with polished reflectors placed behind the chimneys, these lamps could produce a powerful beam of light once the luminous output had been properly concentrated.

Early lighthouse beacons were little more than this. They were later mounted on rotating platforms or stands, which could be driven around by powerful, mechanical clockwork motors. These needed to be wound up every few hours to ensure their continued operation. By placing different lenses in front of the lamps, different colour combinations of light could be achieved. Together with the rotating lamp-base, keepers could produce distinct and easily recognisable lights which could be seen by ships far away. Red and white flashing light might, for example, indicate a particularly dangerous rocky reef which sailors had to avoid.

Throughout the 1800s, lighthouse beacon design continued to improve. Different configurations of lamps and lenses, reflectors and housings were all built, designed, tested and tried, to improve the amount of light produced, the output generated, and the intensity of the beam thrown out from the top of the tower. The next big development from the Argand lamp came in 1822, when French physicist Augustin Fresnel invented the ‘Fresnel Lens’.

A Fresnel lens installed inside a lighthouse. The distinct, curved and rippled effect of the lens meant that all the rays of light coming from the lamp in the center could be angled and concentrated into a single, focused beam.

The Fresnel lens was not a flat sheet of glass, like a window-pane, which was what other lighthouses had used previously – it was a series of prisms – shaped and ground and arranged in such a way that all the angles of glass directed and concentrated the light from its source (the lamp) into a single, solid, unbroken beam. The shape of these prisms not only concentrated the light, but also magnified the output of the lamps, meaning that even a relatively small light could now throw out a beam that could be seen clearly for miles away!

Changing the Lights

As lighthouse technology improved, not only were towers and lenses upgraded, but so were the lights themselves. Originally they were nothing but fires…then candles…then whale oil lamps. In the Victorian era, lighthouses were mostly oil-fired, first with whale-oil (a holdover from the 1700s), and then eventually, kerosene. None of these were really fun to use – they were either really hot, really smoky, really heavy, or really smelly – remember that the lighthouse keeper had to lug fresh candles, fuel or wicks halfway up the tower every time he had to tend the light! Keeping soot and smoke off of the glass and lenses was a regular chore, as well as filling the lamps and trimming the wicks so that they would burn evenly and not produce excessive smoke.

An improvement in lighthouse technology came around in the second half of the 19th century when it was discovered that combining water with the mineral calcium carbide produces flammable acetylene gas. It was easy to produce, relatively safe, and, once a proper system of drip-valves and vents had been created – relatively easy to use and control.

Originally, acetylene lamps were small things – they were used in miners’ lamps, bicycle lamps and the headlamps of steam trains, but as the technology improved, they were also used in lighthouses, replacing the old oil-burning lamps with their wicks and smoke and soot, with cleaner, brighter, gas-fired lamps, which required less maintenance and were easier to operate. All you needed was enough water, and enough carbide to keep the chemical reaction (and the production of gas) going.

Signalling with Light

The classic lighthouse has a single or double-ended beam of white light, which swings and pivots around in a circular motion, shining out to sea. But as lighthouse technology grew more advanced, additional features were added. As early as the 1810s, lighthouse designers were using coloured lenses to create alternating beams of red and white light. The speed and direction of rotation, the combination of colours produced by the lantern, and the paintwork on the lighthouse tower were all methods used to aid sailors at sea, who could pinpoint their position by observing far-off lighthouses through their telescopes. Lighthouses were marked on maps with lists of their peculiar singularities marked next to them. By comparing what they could see through their telescopes with what they could read on their charts, sailors could navigate safely along the coast, fully aware of what was around them.

With the advent in the late 1800s, of electric light, another feature of lighthouses was introduced, previously impossible to implement – flashing lights! Now, not only could lighthouse lanterns spin and change colours, they could also turn on and off. Different combinations of blinking or flashing lights were used to distinguish different lighthouses, and these specific combinations became known as ‘characteristics’, with each lighthouse having a different one to set it apart from its neighbours. Along with its other features, a lighthouse’s characteristic is also included among its information when marked on charts.

The Heyday of the Lighthouse

The lighthouse reached its pinnacle in the second half of the 1800s. Hundreds were constructed around the world in the early 1800s to protect and guide shipping, and even more were constructed in the second half of the 19th century with the rise of regular, steam-powered ocean-going passenger-ships. Lighthouse keepers, their partners, their families and children all became part of the communities they served. Some lighthouses and keepers became famous for actions or events which they participated in or witnessed. By the end of the 1800s, the great flurry of lighthouse-building had ended. So many had been constructed that there was almost a surplus of lighthouses to be had!

The Evolution of the Lighthouse

As the lighthouse became more sophisticated, robust and prominent, certain lighthouses started being used for more than just warning ships at sea. Due to their unique positions, lighthouses were also used as weather-stations. Records of wind direction and strength, air-pressure, temperature and rainfall were kept and published to try and help predict the weather. With the coming of radio, lighthouses, with their great height, were ideal as broadcasting and receiving stations.

As the 20th century dawned, more sophisticated technology started entering lighthouses. Electrification allowed for much more powerful lights, doing away with oil and gas. Some lighthouses which were too remote continued to be gas-fired, but by the second half of the 20th century, improving technology such as solar-panels meant that even the most remote lighthouse could be electrified, and more importantly – automated. The days of the humble keeper were numbered. Lighthouses could now be operated remotely. In the event that maintenance was required, shore-based lighthouses could be inspected by volunteers or the local coastguard. Offshore lighthouses could be accessed by helicopters, and some lighthouses were modified to have landing-pads on their roofs.

Famous Lighthouses

Throughout their long history, some lighthouses have become famous, even infamous. Here are a few of the more noteworthy lighthouses throughout history…

The Cape Race Lighthouse (Newfoundland, 1912)

Built in 1907, the Cape Race Lighthouse served as both a lighthouse and radio transmission-station. It replaced an earlier lighthouse built in the 1850s.

A lighthouse and telegraphic receiving station, the lighthouse at Cape Race was the first land-station to receive wireless telegraph messages and signals of distress from the sinking Titanic, in April, 1912.

The Smalls Lighthouse (Wales, 1801)

Built on the Smalls – a rocky reef off the coast of Wales, the Smalls Lighthouse was the location of a famous incident in 1801, where one lighthouse-keeper died in a freak accident. The surviving keeper had to tend the light (and store his partner’s lifeless corpse) inside the tower for weeks on end. He was eventually driven insane by the nonstop storms, cabin-fever, guilt over his colleague’s death, and sheer isolation. From 1801 to 1980 when lighthouse automation began in the United Kingdom, this incident required that all British lighthouses be manned by at least three keepers at any one time.

The Bell Rock (Scotland, 1810)

Raised in the 1800s, the Bell Rock Lighthouse off the Scottish east coast, was the first great stone lighthouse to be built since Smeaton’s Tower in the 1750s. It’s design and construction were overseen by Robert Stevenson, a Scottish engineer. The lighthouse was so well-designed that it has remained in use to the present day. Stevenson’s success led to a three-generation dynasty of his family producing lighthouses around the United Kingdom. One Stevenson who did not join in the family business was Robert’s grandson; Robert…Louis…Stevenson…who became a children’s author.

Flannan Isles Lighthouse (Scotland, 1900)

Built in the 1890s, the Flannan Isles Lighthouse is one of the most northerly, and remote lighthouses in the world, near the Hebrides Islands off the coast of Scotland.

Remember how in 1801, a lighthouse keeper serving the Smalls Lighthouse died, and the other one was driven mad? To prevent this from ever happening again, the British government decreed that all lighthouses in the British Isles had to be manned by at least three men at all times.

Such was the case in 1900, shortly after the Flannan Isles Lighthouse was first put into operation. Unfortunately, this safeguard was for naught when, in December of that year, a strange chain of events was put into motion.

On the 15th, the steamer SS Archtor was steaming through the Hebrides. The weather was wild and inclement, but despite the heavy seas, the crew on board noticed that, while they could see the lighthouse clearly – they could not see its light, which should’ve been turned on during the storm to guide ships through the treacherous waters.

When the ship made safe harbour three days later, the crew immediately reported this oddity to the local authority – the Northen Lighthouse Board. Established in the 1780s to regulate the construction and operation of lighthouses in Scotland, the Northern Lighthouse Board was responsible for everything that happened to all the lighthouses under its jurisdiction. The heavy seas continued, and it wasn’t until after Christmas that it was deemed safe enough for the Board to send out a relief-boat to the island to examine the light.

Upon arriving, no signs of life could be seen. No trunks or crates of provisions to be restocked, no flags flying, no lights in the lighthouse, and no response when the ship’s captain operated the vessel’s piercing steam-whistles to try and get the lighthouse’s attention. When the ship docked and the crew went ashore, things only got weirder.

Inside the lighthouse, beds were unmade, the light was found to be both topped up with oil, and in working order, there were no signs of forced entry, and no signs of a struggle. Further examinations of the island revealed significant storm-damage along the western shore. In the end, an official investigation by the Northern Lighthouse Board concluded that two keepers had gone out in the storm to respond to this damage and had been swept away by the powerful waves and storm-surges. The third keeper abandoned the lighthouse in an attempt to rescue his companions and was also lost to the sea.

Point Bolivar Lighthouse (USA, 1900)

The Point Bolivar Lighthouse in Texas, USA, rose to prominence (along with its keeper) in 1900, during the famous Galveston Hurricane.

Inaccurate weather forecasts, and a certain amount of overconfidence on behalf of the local weather bureau resulted in thousands of Galvestonians being caught off-guard when, in August of 1900, a powerful hurricane swept through the Gulf of Mexico towards the US Gulf Coast. Galveston, a low-lying city just nine feet above sea-level, had no flood defenses at the time. As people fled from the pounding rain, rising winds and fierce storm-surges, 125 people, including the lighthouse keeper, his assistant, and both their families – sought refuge in the Point Bolivar Lighthouse – the nearest structure of any significant strength – to Galveston.

Everybody in the lighthouse survived the storm, which all but leveled Galveston in the space of a few hours. The keeper, George Claibourne, repeated this feat when, in 1915, Galveston was hit by another hurricane! This time, fifty people sought refuge in the lighthouse and survived. Claibourne died three years later while on duty.

The Fourth Point Lighthouse (Java, 1883)

Built by the Dutch in 1855, as one of a series of lighthouses along the west coast of Java, Fourth Point was designed to guide ships through the Sunda Strait, which runs between Sumatra and Java, the two biggest islands of the Indonesian Archipelago. Operated by the Schuit family (Gerrit, Catharina, and their son Joseph), the Fourth Point Light was regularly visited in early 1883 by Dutch scientist Rogier Verbeek – a pioneering vulcanologist who came to Indonesia (or the Dutch East Indies as they were then called) to study the region’s dozens of active volcanoes.

Verbeek used the vantage point of the Fourth Point’s lantern-room gallery to observe the region’s most famous volcano of all, through his telescope – thirty miles out to sea – known to the natives as ‘Krakatau’.

Known to history, as ‘Krakatoa’.

In August, 1883, Krakatoa erupted so spectacularly that shockwaves and tsunamis rippled all the way around the world, with huge ocean disturbances reaching as far away as India, Africa, Madagascar, and the Pacific Coast of the USA. The eruption was heard as far away as Australia and the Indian Ocean, where sailors thought the sounds of the eruption were from battleships firing off broadsides!

Verbeek was lucky enough to survive the eruption – thousands did not. Among them were all three members of the Schuit family, who were all killed when a volcano-generated tsunami ripped the Fourth Point Lighthouse off its foundations and washed it away.

It was likely that the Schuits felt safe in their lighthouse and did not wish to leave it. Or perhaps they decided to stay to maintain the light – despite the fact that the volcanic ash was so thick that it turned day into night, with ashy rain so thick that the light was rendered completely useless.

All that remains of the original Fourth Point Lighthouse. It was rebuilt in 1885 in a different location.

One ship which the Fourth Point Lighthouse would’ve been trying to guide was the S.S. Governor-General Loudon. Loaded with passengers (eighty-six in total), Chinese coolies being ferried to Sumatra, and the ship’s captain and crew, the Loudon was sailing to Krakatoa for a day-trip. Ever since the volcano had become more active, tourists and locals alike were dying to get up close and personal with a real spitfire!

As they left the island, the volcano started erupting and the Loudon was soon trapped in a volcanic hellstorm which it could not escape from, with over a hundred people on board. Unable to reach safe harbour because the volcanic storm had destroyed the jetties at the port town of Telok Betong (it’s original destination), it’s commanding officer, Captain Lindemann, managed to ride out the storm, first by steering his ship towards the volcano (to absorb the shock of any waves) and then out to sea (to escape the worst of the eruptions). They arrived safely back in Java battered, filthy, scared out of their wits – but nonetheless, alive.

Lighthouses Today

In the 21st century, lighthouses still exist – although it’s been decades since one was built. The majority of lighthouses around today were the ones built in Victorian times, or constructed in the early part of the 20th century. The vast majority of them are automated, and have been, since the 1970s and 80s. Some have been torn down due to redundancy, and some have been turned into historic monuments and tourist-attractions.

The Gay Head Light was built in 1856. It was moved in 2015 to a safer location, further away from the crumbling coastline of Martha’s Vineyard to protect it from imminent collapse.

Some have been saved from demolition by jacking them off their foundations and moving them further inland, or by maintaining their structure and operation with the help of historical preservation societies. In many coastal communities, the local lighthouse is often seen as a beacon, not only of guidance, safety and hope, but also of local town pride. One example is the Gay Head Light, on Martha’s Vineyard on the American east coast, which was moved away from the crumbling coastline in 2015 to save the lighthouse for the local community.

The old Tempelhof Airport, Berlin

The old Tempelhof Airport, Berlin

Come fly with me, let’s fly, let’s fly away…

Come fly with me, let’s fly, let’s fly away…

Welcome to…’The Beehive’!

Welcome to…’The Beehive’!

La Guardia Airport, 1940s. Note the seaplane dock, for Pan Am ‘clippers’

La Guardia Airport, 1940s. Note the seaplane dock, for Pan Am ‘clippers’

Weeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee!!

Weeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeeee!! My fireplace in winter.

My fireplace in winter.

Brass andirons in a fireplace

Brass andirons in a fireplace Andirons at work, supporting a stack of burning firewood

Andirons at work, supporting a stack of burning firewood The grate in my fireplace

The grate in my fireplace.jpg) A brass fireplace fender. Fenders are freestanding, and they can be moved to more easily clean the fireplace between uses

A brass fireplace fender. Fenders are freestanding, and they can be moved to more easily clean the fireplace between uses

Antique cast iron fireback

Antique cast iron fireback The reflector placed behind the grate in our fireplace. A homemade affair easily fashioned out of sheet-metal, a few screws and some metal bars

The reflector placed behind the grate in our fireplace. A homemade affair easily fashioned out of sheet-metal, a few screws and some metal bars The Great Fire of London Screen!

The Great Fire of London Screen! Chim-chimney-chim-chimney-chim-chim-cheree,

Chim-chimney-chim-chimney-chim-chim-cheree,

An antique silver vesta case. Note the striking-ridges on the bottom

An antique silver vesta case. Note the striking-ridges on the bottom

An antique glass ‘grenade’ fire-extinguisher

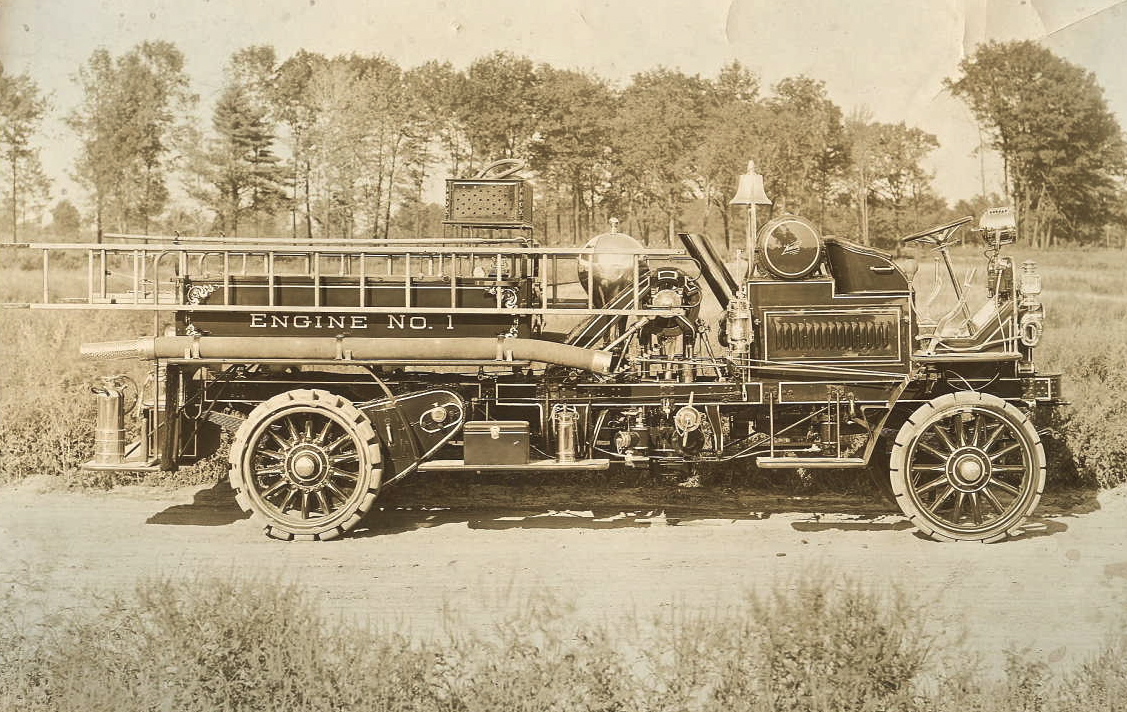

An antique glass ‘grenade’ fire-extinguisher An old fire-pole with important safety-features:

An old fire-pole with important safety-features:

Remington Standard No. 16., Desktop Typewriter., Ca. 1933

Remington Standard No. 16., Desktop Typewriter., Ca. 1933

A Victorian-era camera with separate flash-stand and powder. Note how close the photographer’s right hand is to the igniting flash-powder

A Victorian-era camera with separate flash-stand and powder. Note how close the photographer’s right hand is to the igniting flash-powder “Take your picture, mister?”

“Take your picture, mister?”