From the close of the 1500s, until the end of the Second World War, the British Empire grew, spread and eventually dominated the world, and for two hundred years, from the 1700s until the mid-20th century, was the largest empire in the world.

By the 1920s, the British Empire covered up to 22.6%+ of the globe, covered 13.1 million square miles (33.7 million square kilometers), and its subjects and citizens numbered some 458 MILLION PEOPLE. At its height, 20% of the people on earth were British, or British subjects, living in one of its dozens of colonies, dependencies or protectorates.

The British Empire was, is, and will forever be (until there’s another one), the biggest and arguably, the most famous, of all the Empires that the world has ever seen.

But how was it that the British Empire grew so large? Why was it so big? What was the purpose? What was to be gained from it? Why and how did it collapse? And what became of it? Join me on a journey across the centuries and oceans, to find out what caused the Empire to take root, grow, prosper, dwindle and decline. As this posting progresses, I’ll show the changing flags, and explain the developments behind each one.

The Need for Conquest

The British Empire was born in the late 1500s. During the reign of Henry VIII, England was a struggling country, mostly on its own. Ever since the king’s break from Rome, and the foundation of the Church of England, the Kingdom of England was on its own. Most countries saw it as being radical and nonconformist. It had dared to break away from Catholicism, the main religion of Europe at the time. England was seen as weak, and other countries, such as Spain, were eager to invade England, and either claim it for themselves, or seat a Catholic English monarch on the throne.

It was to protect against threats like these, that Henry VIII improved on what would become England’s most famous fighting force, and the tool which would build an empire:

The British Royal Navy.

The Royal Navy had existed ever since the 1400s, mostly as a hodge-podge of ships and boats. There was no REAL navy to speak of. Ships were simply requisitioned as needed during times of war, and then returned to their owners when war was over. Even in Elizabethan times, British fishing-boats doubled up as the navy.

It was Henry VIII, and his daughter, Elizabeth I, who began to build up the Navy as a serious fighting force, to protect against Spanish threats to their kingdom.

But having a navy was not quite enough. What if the Spanish, or the French, tried to establish colonies elsewhere, where they could grow in strength and strike the British? There is talk of a new world, somewhere far to the West across the seas. If the British could grab a slice of the action, then they would surely be more secure?

It was originally for reasons of security, but eventually, trade and commerce, that the idea of a British Empire was thought up. And it would be these reasons that the British Empire grew, flourished, and lasted, for as long as it did.

The English flag. St. George’s Cross (red) on a white background

British America

In 1707, Great Britain emerges. No longer is it an ‘English Empire’, but a British Empire. Great Britain is formed by the Act of Union between Scotland, England, and the Principality of Wales.

By 1703, England and Scotland had already been ruled by the same family (the Stuarts), for a hundred years, ever since Elizabeth I died in 1603, and her cousin, King James of Scotland inherited her kingdom as her closest surviving relative.

.svg/250px-Union_flag_1606_(Kings_Colors).svg.png) The flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain. The red St. George’s Cross with the white background, over the white St. Andrew’s Cross and blue background, of Scotland. This would remain the flag for nearly 100 years, until the addition of Ireland

The flag of the Kingdom of Great Britain. The red St. George’s Cross with the white background, over the white St. Andrew’s Cross and blue background, of Scotland. This would remain the flag for nearly 100 years, until the addition of Ireland

It seemed only to make more sense, therefore, that since England and Scotland were ruled by the same family, they may as well be the same kingdom. The Kingdom of Great Britain.

By this time, British holdings had grown to include Newfoundland, and more and more holdings on the North American mainland. At the time, America was being carved up by the great European powers. France, Britain, Holland and Spain were all fighting for a slice of this new, delicious pie called the New World.

And they were, quite literally, fighting over it. Ever heard of a series of conflicts called the French and Indian Wars? From 1689 until 1763, the colonial powers fought for control over greater parcels of land on the American continent. America had valuable commodities such as furs, timber and farmland, which the European powers were eager to get their hands on.

By the end of the 1700s, Britain’s colonial ambitions and fortunes had changed greatly. It retained Newfoundland, but had gained Canada from France, but had lost its possessions in America to these new “United States” guys. Part of the deal with France over getting their Canadian land was that the French be allowed to stay. As a result, Canada at the time (in the 1790s), was divided into Upper and Lower Canada (Ontario, and Quebec, today). Even in the 21st century, we have French-speaking Canadians.

British colonies in the Americas wasn’t just limited to the top end, either. Since the mid-1600s, the British also controlled Jamaica (a colony taken, not from the French, but this time, from the Dutch). British rule of Jamaica lasted from 1655, until the late 1950s!

Just as its former American colonies had provided Britain with fur pelts and cotton, Jamaica was also colonised so that it could provide the growing empire with a valuable commodity – in this case, sugar. In the 1500s, sugar was incredibly rare, and the few countries which grew sugarcane were far from England. Extracting and transporting this sweet, white powder was labour-intensive and dangerous. But now, England had its own sugar-factory, in the middle of the Caribbean.

British India

It was during the 1700s, that the British got their hands on one of the most famous colonies in their growing empire. They might have lost America and gained Canada, but in the 1750s, they gained something much more interesting, thanks to an entity called the East India Trading Company, a corporation which effectively colonised lands on behalf of the British.

In 1800, another Act of Union formed the United Kingdom of Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) and Ireland. The flag now depicts the diagonal red cross of St. Patrick, over that of St. Andrew, but with both below the cross of St. George. This has remained the British flag for over 200 years, up to the present day

Formed as a trading company to handle imports and exports out of countries in the Far East, the East India Company (founded in 1600), got their hands on the Subcontinent of India. And for a hundred years, between 1757 and 1858, more or less controlled it for the British Government.

Indians were not happy about being controlled by a company. True, it had brought such things as trade, wealth, transport, communications and education to the Indian Subcontinent, but the company’s presence was not welcomed.

The end of Company Rule in India came in 1857, a hundred years after they had established themselves there. The Indian Rebellion of 1857 occurred when the Indian soldiers who worked for the Company rebelled over the Company’s religious insensitivity. Offended by the liberties and insults which the Company took, and dished out, Indian soldiers under Company pay, revolted against their masters.

The rebellion spread around India, and fighting was fierce on both sides. It eventually ended in 1859, with an Indian defeat, but at least it also ended Company Rule in India.

However, the British were not willing to let go of India. It had too many cool things. Like spices and ivory, exotic foods and fine cloth. Oh, and a little drug called opium.

In the end, the British formed British India (also called the British Raj), in the late 1850s.

To appease the local Indian population and prevent another uprising, a system of suzerainty was established. Never heard of it? Neither had I.

Suzerainty is a system whereby a major controlling power (in this case, Britain), rules a country (India), and handles its foreign policy as well as other controlling interests. In return, the controlling power allows native peoples (in this case, the Indians) to have their own, self-governing states within their own country.

When applied to India, this allowed for 175 “Princely States”. The princely states were ruled by Indian princes, or minor monarchs, (the maharajahs), while the other states within India were ruled by the British. As such, India was thereafter divided into “British India”, and the “Princely States”.

British India was ruled by the Viceroy of India, and its legal system was determined by the big-wigs in London. The Princely States were allowed to have their own Indian rulers, and were allowed to govern themselves according to their own laws. Not entirely ideal, but much better than being ruled over by a trading company!

The Indians largely accepted this way of life. It was in a way, similar to their lives under the Mongol Empire before. It was a way of life with which they were familiar and comfortable with. In return for various concessions, changes and improvements, the Indians would allow the British control of their land.

The number of princely states rose and fell over the years, but this system remained in place until Indian independence was granted by Britain in the years after the Second World War.

The Viceroy of India was the head British representative in India, and ruled over British India, and was the person to whom Indian princes went to, if they had concerns about British involvement within India.

Pacific Britain

Entering the 1800s, Britain became more and more interested in the Far East. Britain realised that establishing trading-posts and military bases in Asia could bring them the riches of the Orient and a greater say in world affairs. To this end, it colonised Malaya, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Fiji, Penang, Kowloon, Malacca, Ceylon (modern day Sri Lanka) and Burma. It even tried to colonise mainland China, but only succeeded in grabbing a few small concessions from the Qing Government, such as Shanghai.

The Pacific portion of the British Empire was involved heavily in trade and commerce, and a great many port cities sprang up in the area. Singapore, Hong Kong, Rangoon, Calcutta, Bombay, Melbourne and Sydney all became major trading-stops for ocean-liners, cargo-ships and tramp-steamers sailing the world. From these exotic locales, Britain could get gold, wool, rubber, tin, oil, tea and other essential, exotic and rare materials.

The British were not alone in the Pacific, so the need for military strength was important. The Dutch, the Germans and the French were also present, in the Indies, New Guinea, and Indochina, respectively.

Britain and the Scramble for Africa

The Industrial Revolution brought all kinds of new technology to the world. Railways, steamships, mills, factories, mass-production, telecommunications and improved medical care, to name but a few. And Britain, like other colonial powers, was eager to see that its colonial holdings got the best of these new technologies that they could.

However, these improvements also spurred on the desire for greater control of the world. And from the second half of the 1800s, saw the “scramble for Africa“.

The ‘Scramble’ or ‘Race’ for Africa, was a series of conquests by the colonial powers, to snatch up as much of the African continent as they could. The Dutch, Germans, French and British all duked it out to carve up hunks of Africa.

The French got most of northwest Africa, including the famous city of Casablanca, in Morocco. They also controlled Algeria. The British got their hands on Egypt, and a collection of holdings (including previous Dutch colonies, won from them after the Boer Wars) which they called the Union of South Africa. The British also got their hands on Nigeria, British East Africa (“Kenya”) and the Sudan. Egypt was never officially a British colony, but remained a British protectorate (a country which Britain swore to provide military assistance, or ‘protection’ to). It was a crafty way of adding Egypt to the British Empire without actually colonising it.

British interest in Egypt and southern Africa was related less to what Egypt could provide the empire, and more about what it would allow the empire to do. Egypt was the location of the Suez Canal, and important shipping-channel between Europe and the Far East. Control of Egypt was seen as essential by the British, for quick access to their colonies in the Far East, such as India, Singapore and Australia.

A map of the world in 1897.

A map of the world in 1897.

The British Empire comprised of any country marked in pink

Justification for Empire

As the British Empire grew during the Victorian era, and the early 20th century, with wars of conquest, and with other European powers, some sort of justification seemed to be wanting. Why should Britain control so much of the world? What gave it this right? How did it explain it to the other European powers, or the the Arsenal of Democracy that was the rising power of the United States? How did it justify the colonisation of countries to the peoples of the countries which they colonised?

Leave it to a writer to find the right choice of words.

Rudyard Kipling, author of “The Jungle Book“, was the man who came up with the phrase, “The White Man’s Burden“, in a poem he wrote in 1899.

Put simply, the burden of the white man; the white, European man, is to bring civilisation, culture, refinement and proper breeding and upbringing to the wild and uncouth savages of the world. Such as those savages likely to be found in Africa, the Middle East and the isolated isles of the South Pacific.

Britain, being naturally the most civilised, cultured, refined and most well-bred country on earth, producing only the most civilised, cultured, refined and most well-bred of citizens, was of course, the best country on earth, with the best people on earth, to introduce these wonderful virtues to the savages of the world. And to bring them up to date with technology, science, architecture, engineering, and to imbue them with good Christian virtues. Britain after all, had the best schools and universities: Eton, Harrow, Oxford, Cambridge, St. Peter’s., the list goes on. They were naturally God’s choice for teaching refinement, culture and all that went with it, to the rest of the world.

This was one of the main ways in which Britain justified its empire. By colonising other nations, it was making them better, more modern, and more cultured, in line with the West. It brought them out of the Dark Ages and into the light of modernity.

The British colonised certain countries (such as Australia) under the justification of the Ancient Roman law of “Terra Nuliius“. Translated, it means “No Man’s Land”, or “Empty Land” (“Terra” = Land, as in ‘terra-firma’; “Nullius” = Nothing, as in ‘null and void’).

By the British definition of Terra Nullius, a native people only had a right to sovereignty over its land if it changed the landscape in some manner, such as through construction, industry, craft, agriculture, or manufacturing. It had to show some degree of outward intelligence beyond hunter-gatherer society and starting a fire with two sticks.

They did not recognise these traits in the local Aboriginal peoples, and saw no evidence of such activites. Therefore, they claimed that the land was untouched, and the people had minimal intelligence. Otherwise, they would’ve done something with their land! And since they hadn’t, they had forfeited their claim to sovereignty over their land. Under the British definition of Terra Nullius, this meant that the land was theirs for the taking. Up for grabs! Up for sale! And they jumped on it like a kangaroo stomping on a rabbit.

The Peak of Empire

British control of the world, and the fullest extent of its imperial holdings came during the period after the First World War. One of the perks of defeating Germany was that Britain got to snap up a whole heap of German ex-colonies. A lot of them were in Africa, but there were also some in the Far East, most notably, German New Guinea, thereafter simply named ‘New Guinea’ (today, ‘Papua New Guinea’).

It was during the interwar period of the early 20th century that the British Empire was at its peak. By the early 1920s, Britain had added such notables as the Mandate of Palestine (modern Israel), and Weihai, in China, to its list of trophies (although its Chinese colony did not last very long).

The extent of the British Empire by 1937. Again, anything marked in pink is a colony, dominion, or protectorate of the British Empire

The extent of the British Empire by 1937. Again, anything marked in pink is a colony, dominion, or protectorate of the British Empire

The Colony of Weihai

For a brief period (32 years), Great Britain counted a small portion of China as part of its empire. Britain already had Hong Kong, but in 1898, it added the northern city of Weihai to its Oriental possessions. Originally, it was a deal between the Russians and the British. So long as the Russians held onto Port Arthur (a city in Liaoning Province in northern China), the British could have control of Weihai.

In 1905, the Russians suffered a humiliating defeat to the Japanese, in the Russo-Japanese War. Part of the Russian defeat was the Japanese occupation of Port Arthur. Britain then made a deal with Japan that they could remain in Weihai so long as the Japanese held onto Port Arthur. To appease the Chinese, the British signed a lease with the Chinese for twenty-five years, agreeing to return Weihai to the Chinese Imperial Government when the lease expired, which in 1905, meant that Weihai would be returned in 1930.

The Glory of the British Empire

The early 20th century was the Golden Age of the British Empire. From the period after the Great War, to the onset of the Second World War, Britain was powerful, far-reaching and dominant. British culture, customs, legal systems, education, dress, and language were spread far around the world.

Children in school learnt about the Empire, and the role it played in making Britain great. People in countries like New Zealand and Australia saw themselves as being British, rather than being Australian or New Zealanders. After the First World War, monuments and memorials were erected to those who had died for the “Empire”, rather than for Australia, New Zealand, or Canada. Strong colonial and cultural ties held the empire together and drew soldiers to fight for Britain as their ‘mother country’, who had brought modernisation, culture and civility to their lands.

The Definitions of Empire

If you read any old documents about the British Empire, such as maps, letters, newspapers and so-forth, you’ll notice that each country within the empire is generally called something different. Some are labeled ‘colonies’, others are ‘mandates’, some are ‘protectorates’, and a rare few are named as ‘dominions’. And yet, they were all considered part of the Empire. What is the difference between all these terms?

The Colonies

Also sometimes called a Crown Colony, a colony, such as the Colony of Hong Kong, was a country, or landmass, or part of a landmass, which was ruled by the British Government. The government’s representative in said colony was the local governor. He reported to the Colonial Office in London.

The Protectorates

A protectorate sounds just like what it does. And it can be a rather cushy arrangement, if you can get it. As the name implies, a country becomes a protectorate of the British Empire when it allows the Empire to control certain parts of its government policies, such as foreign policy, and its policies concerning the country’s defence from foreign aggression. One example of this is the Protectorate of Egypt.

In return for allowing the British to control such things as foreign relations and trade, and in return for having British military protection against their enemies, a country’s ruler, or government, could continue running their country as they did, with certain things lifted off their shoulders. But with other things added on. For example, the British weren’t interested in Egypt for the free tours of the Valley of the Kings. They were interested in it because of the Suez Canal, the water-highway to their jewel in the Far East, known as India! In return for use and control of the Canal, the British allowed the Egyptians to run their own country as they had always done.

The Mandates

The most famous British mandate was the Mandate of Palestine (modern Israel).

In the 1920s, the newly-formed League of Nations (the direct predecessor to the U.N.) confiscated former German and Turkish colonies, and distributed them among the two main victors of the Great War; Britain, and France. Basically, Britain and France got Turkish and German colonies as ‘prizes’ or ‘compensation’ of the war.

Legally, these mandates were under the control of the League of Nations. But the League of Nations was well…a League! A body. Not a country. And the League couldn’t control a mandate directly. So they passed control of these mandates to the victors of the Great War.

The Dominions

On a lot of old maps, you’ll see things like the Dominion of Canada, the Dominion of Australia, and the Dominion of New Zealand. What are Dominions?

Dominions were colonies of the Empire which had ‘grown up’, basically. They were seen as highly-developed, modern countries, well-capable of self-governance and self-preservation, without the aid of Mother England. They were like the responsible teenagers in an imperial family, to whom old John Bull had given them the keys to the family car, on the condition that they didn’t trash it, or crash it, and that they returned it in good working order.

The Dominions were therefore allowed to be more-or-less self governing. After 1930, the Dominions became countries in their own rights, no-longer legal colonies. But they were still seen as being part of the Empire, and bound to give imperial service if war came. Indeed, when war did come, all the Dominions pledged troops to help defend the Empire.

There was talk of making a ‘Dominion of India’. India wanted independence, but Britain was not willing to let go of its little jewel. It saw making India a Dominion as a happy compromise between the two polar options of remaining a colony, or becoming totally independent. However, a little incident called the Second World War interrupted these plans before they could be fully carried out.

War and the Empire

The British Empire was constantly at war. In one way, or another, with one country, or another, it was at war. The French and Indian Wars, the American War of Independence, the War of 1812, the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars, the Opium Wars, the Crimean War of the 1850s, the First and Second Afghan Wars. The Mahdist War of 1881 lasted nearly twenty years! Then you had the Boer War, the Great War, and the Second World War.

One reason why Britain managed to engage in so many wars, and survive, and in some cases, prosper from them, was due in a large part to its empire. In very few of these wars did Britain ever fight alone. Even when it didn’t have allies fighting alongside it, Britain’s fighting force was comprised of both home-born Englishmen, but also a large number of imperial troops. Indians, Australians, Canadians, New Zealanders, and Africans. They all signed up for war! When Australia became a nation in 1901, instead of being a gaggle of colonies, Australian colonial soldiers, freshly-returned from the Boer War in Africa, marched through the streets of Australian cities as part of the federation celebrations.

“The Sun Never Sets on the British Empire”

The cohesion of the British Empire began to crumble during the Second World War.

Extensive demilitarisation during the interwar years had greatly weakened Britain’s ability to wage war. Britons and their colonial counterparts became complacent in their faith in the might of the British Navy, which for two hundred years, had been the preeminent naval force in the world.

Defending the Empire became increasingly difficult as it grew in size. In the years after WWI, Britain believed that the “Singapore Strategy”, its imperial defence-plan based around Singapore, would protect its holdings in the Far East.

The strategy involved building up Singapore as a military stronghold for both the army, navy and Royal Air Force. In the event of Japanese aggression, the Navy could intercept Japanese warships, and the air-force and army could protect Singapore from land or air-based invasions. The Navy would be able to protect Singapore, Hong Kong and Malaya from Japanese invasion, or would be able to drive out the Japanese, if they did invade.

Under ideal circumstances, such a plan would be wonderful. But in practice, it fell flat. The British Royal Navy simply did not have the seapower that it once had. It had neither the ships, sailors, airmen or aircraft required to protect both England and Singapore. Great Britain was having enough troubles defending its waters against German U-boats, let alone Japanese battleships and aircraft carriers in the Pacific.

On top of that, Singapore simply wasn’t equipped to hold off a Japanese advance, from any direction under any means. Even though the British and colonial forces on Singapore vastly outnumbered those of the Japanese, the British lacked food, ammunition, firearms, artillery, aircraft, and naval firepower, resources stretched thinly enough already due to British disarmament during the 1920s and 30s.

The fall of Singapore after just one week of fighting the Japanese was a great shock to the Empire, especially to Australia and New Zealand, who had relied on Singapore to hold back the Japanese. In Australia, the fall of Singapore showed the government that Britain could not be trusted to protect its empire.

When Darwin was bombed, defying orders from Churchill, Australian prime minister John Curtin ordered all Australian troops serving overseas (in the Middle East and Africa) to be returned home at once. For once, protection of the homeland was to take precedence over protection of the Empire, since the Empire wasn’t able to provide protection, Australia would have to provide its own, even if it came at the expense of keeping the Empire together.

Even Winston Churchill, an ardent Imperialist, realised the futility of protecting the entire empire, and realised that certain sections would be impossible to defend without seriously compromising the defence of Great Britain. British colonies in Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore and in the Pacific islands gradually fell to Japanese invasion and occupation.

By the 1930s, the Empire was already beginning to fall apart. Independence movements in countries like Iraq (a British mandate from 1920), Palestine (a mandate since 1920) and India, was forcing Britain to let go of its imperial ambitions.

For the most part, independence from Britain for these countries came relatively peacefully, and in the years after the Second World War, many of the British colonies gained independence.

Independence was desired for a number of reasons, from the simple want for a country’s people to rule themselves, the lack of contact and cohesion felt with Great Britain, or in some cases, the realisation or belief that the British Empire could not protect them in times of war, as had been the case with Singapore and Hong Kong.

The British Commonwealth

Also called the Commonwealth of Nations, the British Commonwealth was formed in the years during and after the Second World War. The Commonwealth is not an empire, but rather a collection of countries tied together by cultural, historical and economic similarities. Almost all of them are former British colonies.

The Commonwealth recognises that no one country within this exclusive ‘club’ is below another, and that each should share equal status within the Commonwealth. It was formed when the British realised that some of their colonies (such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada) were becoming developed, cultured, civilised and powerful in their own rights. So that these progressive countries did not feel like Britain’s underlings, the Commonwealth was formed. Now, the Dominions would not be above the Colonies, and the colonies would not be below Britain, they would all be on the same level, and part of the same ‘club’, the British Commonwealth.

The Empire Today

The sun has long since set on the British Empire, as it has on nearly all great empires. But even after the end of the empire, it still makes appearances in the news and in films, documentaries and works of fiction, as a look back at an age that was.

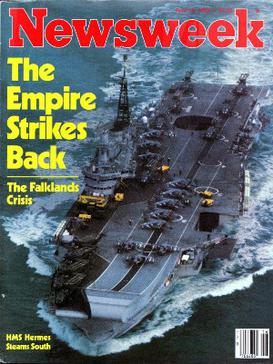

During the 1982 Falklands War, a conflict that lasted barely three months, the famous New York magazine “Newsweek” printed this cover:

An imperial war without the Empire…

An imperial war without the Empire…

In four simple words, this title comments on the recent Stars Wars film of the same name, the former British Empire, and on the fabled might of the Royal Navy, which had allowed the formation of that empire, so many hundreds of years ago.

Imperial Reading and Watching

The British Empire lasted for hundreds of years. It grew, it shrank, it grew again, until it came to dominate the world, spreading British customs, ideals, education, government, culture, food and language around the globe. This posting only covers the major elements of the history of the British Empire. But if you want to find out more, there’s plenty of information to be found in the following locations and publications. They’ll cover the empire in much greater detail.

“The Victorian School” on the British Empire.

Documentary: “The Fall of the British Empire“

Documentary Series: “Empire” (presented by Jeremy Paxman).