…or “the devolution of the pen from the quill to gel”, as suggested by one of my readers.

The ability to read and write has always been one of mankind’s greatest achievements. Reading and writing allowed for the recording, protection and spread of ideas, information and new discoveries. But we would never have been able to read about all these great inventions, discoveries and ideas if someone hadn’t first discovered how to write them down. So, what were the first writing instruments, and how did they evolve over time?

The First Pens.

The first writing instruments were stylii, that is, sticks which were specially-shaped so as to press wedge-shaped characters into soft wax or clay tablets. Created by the Sumerians several thousand years ago, these stylii and the wedges which they pressed, became the first form of writing, known as ‘cuneiform’. By arranging the wedge-shapes by size, distance and design, the Sumerians created the first alphabet and system for writing.

For several years, cuneiform writing was the only form of writing available. From cuneiform, came brush-writing. Brushes with thin tips dipped in inks made from water and natural dyes made from fire-soot, became the first pens. These pens allowed for more a more clearer form of writing than could be produced on wax or clay tablets, by making marks on a type of cloth called papyrus, which was made from reeds. Papyrus is the word from which we get the modern ‘paper’. The peoples of some countries (mostly East Asian countries) still use brush-pens today, to write characters in Chinese, Japanese or any other Asian language.

With trade and travel, writing gradually spread around Europe and the Mediterranean Basin. The Sumerians who invented writing, lived in the Mediterranean, so the nearest countries, such as Eygpt and Italy and Germany and Greece, were the first places to pick up on this new invention of ‘writing’.

The Egyptians created a form of picture-writing known as hieroglyphs, again, using brush pens. While very pretty, hieroglyphs took a long time to write, and they could be difficult to read. It was evident that a clearer form of writing was required, and with it, better tools.

The Romans are responsible for creating the alphabet which most of us recognise today. Originally, the alphabet was all in capitals and all the letters were very angular. The letter ‘u’ was written as a ‘v’. This was because the Romans wrote their text (in Latin) onto stone slabs, using hammers and chisels. The writing produced was easy to read; it was clear legible and faster (in a manner of speaking), than pictograph writing. But hammering letters and words into a block of stone with a chisel and a hammer was tiring and slow, and you couldn’t make curves!

Reeds and Quills.

Eventually, people moved back to inks and papers. The Romans kept extensive records of a lot of things which went on in their empire, and to do this effectively, they turned to scrolls of papyrus, and a new kind of pen…the reed. Reed pens were pretty easy to work with. You took a sharp knife and made a diagonal cut in the tip of the reed. You continued cutting until you had a triangular point. You put a slit down the middle of the point with your knife, and then dipped the reed into the ink to write with. Reeds were sufficient, but constant re-sharpening and cutting made them impractical. Ink softens the reed as you write, and once the reed got too soft, you had to start cutting out another pen-point.

By the medieval period, yet another type of writing instrument had replaced the reed. The quill.

The quill was a feather, a big, primary flight-feather from the wing of a large bird (usually a goose). Quills were plentiful, but they took a while to make. It went something like this:

Having found the feather, you first had to wash it. Then you had to dry it. You then took out a knife and cut off all the barbs (the soft, frilly bits on the sides of the feather), which left you with a long, relatively stiff, strong shaft. Contrary to what you see in the movies, you didn’t write with the barbs still on the feather because they just got in the way.

Once the pen was cleaned, dried and de-barbed, you buried it in sand and put it over a fire. Heating it up like this in the sand caused the pen to dry out and become nice and stiff and hard. Once the pen was removed from the sand and the fire and was cleaned properly, you took out a knife and started cutting the tip into the feather (much like with a reed pen).

Because the quill was stronger and stiffer, it could write significantly better than the reed pen. Different ways of cutting the pen-point allowed for different styles of writing. It’s at this time that the German Gothic or ‘Blackletter’ style of writing, synonymous with the Middle Ages, began to appear. By cutting the quill-point a certain way, you could create text with wide up-down strokes, and thin horizontal strokes. It was during this period, that the writing-surface changed from papyrus to vellum (dried animal hides) and eventually to paper.

The quill lasted for several hundred years. Several great documents such as the Bible, the American Declaration of Independence and many classic works of literature from the 18th century, were written with quills. The diary of Samuel Pepys, the famous English naval administrator of the 1600s, would have been written entirely with a quill. William Shakespeare wrote all his plays with a quill. Even though the quill had to be sharpened and reshaped every so-often, much like the reed pen before it, for centuries, it was the only pen that people had. The small knives which we have today which are called ‘pen-knives’ comes from the period when the quill was king. Your pen-knife was the tool which you used to cut the tip of your pen with. No pen-knife, no quill, no writing.

Quills remained the mainstay of writing for several centuries. The flexible nature of the pen-points, after they had become softened somewhat, with ink, allowed people to create even more styles of writing. The expressive, decorative, loopy, thick-thin styles of handwriting that came about during the 17th and 18th centuries, such as roundhand, Copperplate and Spencerian, were the direct, natural result of the writing properties of the quill.

The Steel Pen.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, a little something called the Industrial Revolution swept through Europe. With the power of wind, water, fire and steam, machines began to be manufactured which could produce all kinds of things. All these new inventions naturally created a lot of paperwork. Mankind needed a better kind of writing instrument to put all the wages and salaries and information down on paper. Then one day, an intelligent man thought to himself that if pen-points were made of something tougher, stronger and which would last longer, he could make a fortune. What if pen-points, instead of being the easily-worn-out tips of feathers, were actually made of something tough and durable…like…metal?

Using steam-powered presses, special moulds and sheets of metal, the first mass-production of metal pens were created, at the end of the 18th century. While revolutionary, it would not be until the 1830s that real, practical mass-production of steel writing-pens, which could be sold in little boxes at stationers’ shops, really began.

The invention of a simple, cheap, durable pen-point which could be made in its thousands, revolutionised the writing world. Now, if you wanted to write, all you had to do was go down to the shop and buy a box of pens and a pen-holder (the long shaft which the metal points fitted into), and you could write away to your heart’s content. Such was the popularity of this new invention that in schools, it lasted until the 1930s.

Steel pens, of the kind which started being made in the 1830s.

The metal pen caused all kinds of changes in the world. For the first time, cheap, reliable pens were available in their thousands to the masses, which greatly boosted literacy rates and helped to improve education. Great stories such as the ‘Sherlock Holmes’ canon were written the steel pen, as well as works by Mark Twain and Jules Verne. Now, authors could concentrate on their thoughts, rather than on whether their pen-point was going to snap in half and spray ink all over their desks.

While the metal pen allowed for quicker and more comfortable writing, one crucial problem still remained. Portability.

The Birth of the Fountain Pen.

Up to this point, all pens were ‘dip-pens’. You sat at your desk with a quill or a steel pen, and an inkwell or a bottle of ink nearby, to dip your pen into every few minutes, while you were writing. As yet, nobody had discovered a way of creating a reliable, portable writing instrument that used ink. The idea of a pen that held its own ink-supply had been around for centuries, but early fountain pens were frustrating and unreliable at best. Inkflow was erratic and unpredictable. A pen might write smoothly, or more often, it would leak out ink or write haltingly or not at all.

That all changed in the 1880s, with the ingenuity of a frustrated and angry insurance-broker by the name of Lewis Edson Waterman.

Popular pen-lore will tell you that in 1883, Waterman, a somewhat successful insurance-broker, was talking turkey with a rich client. The client had a nice, fat contract worth several thousand dollars, sitting on the deal-table. All Waterman had to do was take out a pen and sign on the dotted line. Waterman was so excited about this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity, that he brought with him, a newfangled ‘reservoir’ pen…today known as a ‘fountain pen’. While signing the contract, Waterman’s pen threw a sickie, and chucked up black ink all over the precious piece of paper. Waterman was mortified and ran off to find another pen to seal the deal with. By the time he had, the client had upped and left and sealed the deal with another broker, leaving Waterman fuming and frustrated. The story then goes that he charged off to his brother’s farm to make improvements to the fountain pen which we all thank him for today.

1910s Mabie-Todd & Co. Swan eyedropper filler, similar to the kind of pens that existed in Waterman’s lifetime.

That story, while it makes for fascinating marketing, is generally believe to be untrue (and is even debunked by the Waterman Pen Co. itself). But what really did happen was that Waterman had made one crucial discovery.

The importance of air-pressure in making a successful pen.

Before Waterman had his brainwave, all the fountain pens in the world leaked. They leaked in buckets or they leaked not at all, refusing to write, sealing up like oysters. It was Waterman who learnt how to break open the oyster to get at the stuff inside, but without having it gush out like a firehose. Using a thin, hard-rubber rod with little slits cut into it, called a ‘feed’, Waterman learnt that, properly seated underneath the nib of a fountain pen, it could regulate the flow of ink purely by air-pressure. As ink went down two of the channels cut in the feed, air went up the third channel into the ink-reservoir, creating a balanced air-pressure which allowed for a safe and dependable flow of ink. That same principle has guided all pen-makers ever since.

Diagram showing the three-channel feed (right), which allows for proper regulation of inkflow in fountain pens

Picture by Richard F. Binder; richardspens.com

With a pen that would at last write reliably, Waterman had made a breakthrough which would net him thousands of dollars. Soon after, he founded the Waterman Pen Company in 1884. And while poor Mr. Waterman died less than 20 years later in 1901, his ingenuity had paved the way for greater things to come.

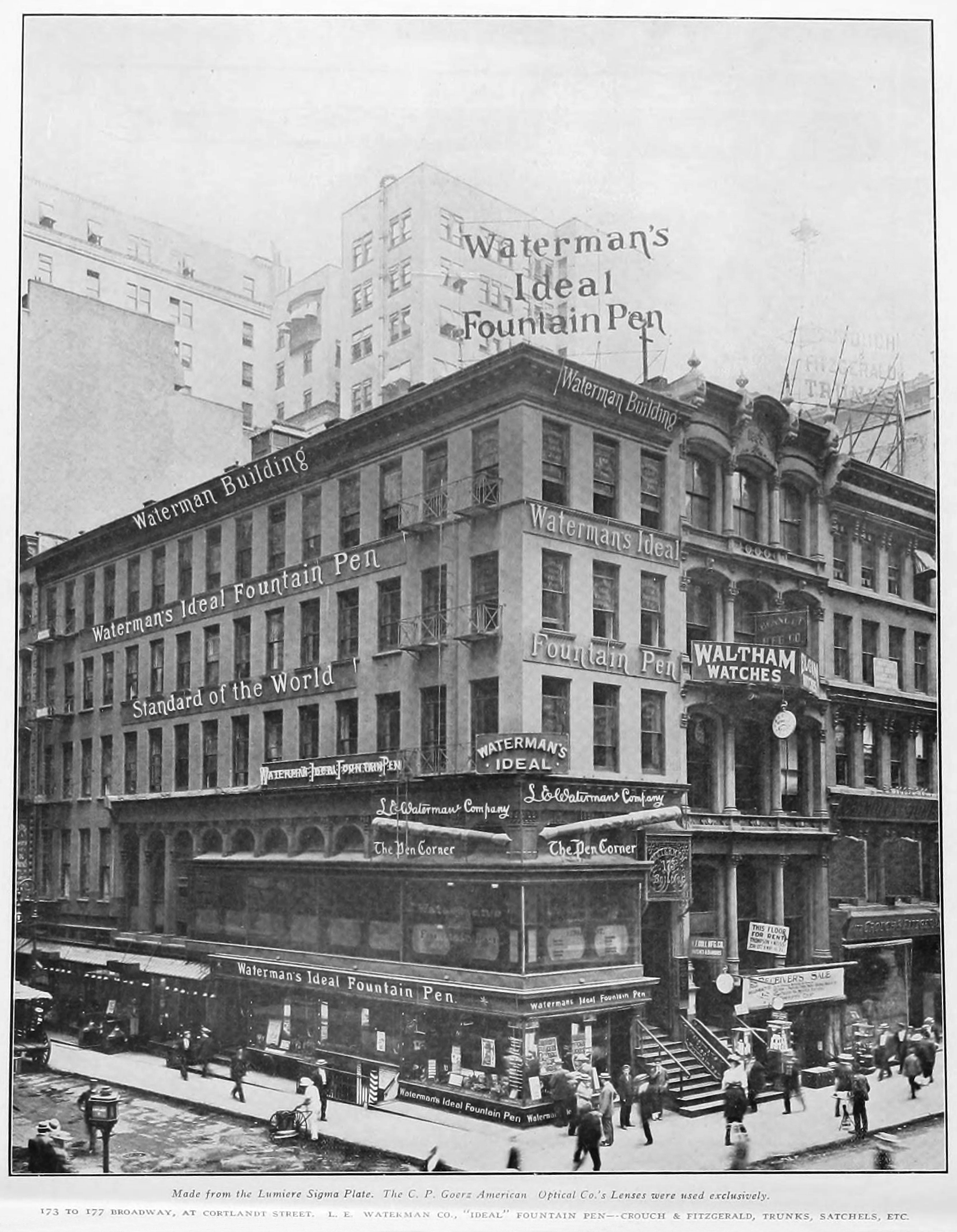

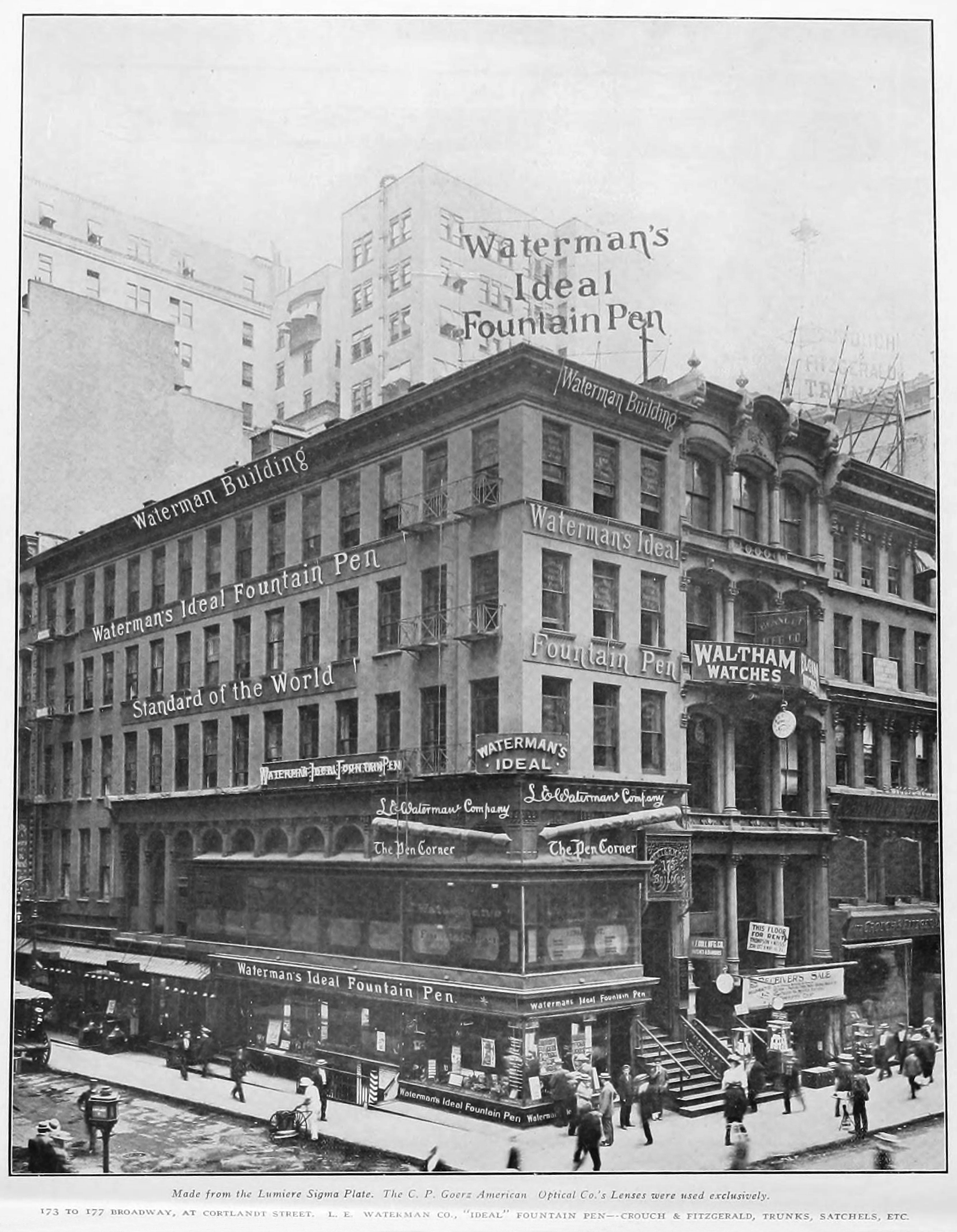

The Waterman Pen Company in Manhattan, New York City, ca. 1910