Hollywood! A magical, amazing, magnificent, fascinating, fantasmagorical funpark where dreams are made. Today, Hollywood is the most famous place in the world for making blockbuster feature films. It’s where movie-stars earn multi-million dollar paychecks, it’s where aspiring actors hope to make it, and make it big…one day. It’s where directors create their masterpieces and where producers hope to push their latest pitch. It’s the dream factory where thousands of people work to produce fantasies that millions of others will buy. But where did this dream factory come from and how did it come into existence? Was Hollywood always around? Or was it accidently washed onto the shores of California a couple of centuries ago? Or did the aliens drop it out of the sky on their way to Mars? Who knows?

Well, we’re going to find out.

What is ‘Hollywood’?

The first thing we need to understand is the name ‘Hollywood’ and where it is. It is, admittedly, a very generic name. Just like there are lots of places named ‘Springfield’ or ‘Townsville’ or ‘Harrison’ (maybe), there are lots of places in the United States named ‘Hollywood’. Don’t believe me? Go look at a map. In America alone, there’s at least a dozen towns named ‘Hollywood’ and three places named ‘Hollywood’ in Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland. But when most people say ‘Hollywood’, we all know the one they’re talking about.

Hollywood, California.

To be clear, Hollywood is not actually a town. It’s a district of the City of Los Angeles, California. The area known as ‘Hollywood’ today started in the second half of the 19th century as just another suburb of Los Angeles. Developed between the 1880s and the early 1900s, Hollywood takes up a space of 500 acres. The area is designed as a quiet, upperclass neighbourhood where the wealthy, the high rollers and the fat-cats can live in luxury. To advertise this wonderful new part of town, an enormous sign is erected on the hills overlooking Los Angeles.

“HOLLYWOODLAND”

The Early Filmmaking Industry

Moving pictures started as an experiment at the close of the 19th century. By the first decade of the 20th century, people were beginning to hear about these new moving images and the possibility that they held for entertainment. Film studios were small concerns, few and far between. Films were cheap thrills. You could go to a simple cinema in town and pay five cents to watch a short flicker-show…which almost literally coined the term…‘Nickelodeon’.

But by the 1910s, interest in the filmmaking industry began to grow as people saw the potential of this new technology, and Hollywood would be there every step of the way.

The year is 1912. Hollywood is about to take off. Two years previously, the first film ever made in Hollywood went on show. It was just seventeen minutes long. A far cry from the three-hour-long, multipart blockbusters we know today. But it was a start. In 1912, the first official film-studio opened in Hollywood, called Nestor Studio. The first official Hollywood film, made in a Hollywood studio, would come out two years later in 1914, directed by one of the legends of the Golden Age of Hollywood. His name was Cecil B. DeMille.

By 1915, the American film industry (before then, based mostly in New York) had started moving to Los Angeles. The American film industry was born.

The Golden Age of Hollywood

The Silent Era

During the 1910s, Hollywood was still making a name for itself. Although film was becoming more widespread, it was still in a rather rudimentary state. The idea of film credits were only just being thought-of. It was only once cinema had a firm foothold as an entertainment medium that people decided it might be a good idea to add lists of details before and after films, so that people could tell who produced, directed and starred in the various films then rolling across the screens of the world.

The 1920s saw the rise of Hollywood. The first stars were born. People like Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin and Rudolph Valentino. Films during these early years were crude. Without the benefit of synchronised audio, actors relied on exaggerated body-language and close-ups of facial-expressions to convey emotional messages such as anger, frustration, horror and comedy. Intertitles, a staple of films of this era, conveyed important information to the audience such as important bits of dialogue, scene-changes or important story-elements.

Many terms used in the film-industry today survive from this early era. Today, a ‘flick’ is a feature film or a ‘movie’. A ‘film’. ‘Flick’ came from the propensity of early images to flicker across the screen as the film-reels rolled over the projection-lights. ‘Movie’ naturally comes from the bigger word ‘moving picture’ and ‘film’ from the delicate and highly combustable cellulose nitrate film that early films were produced on – So flammable that it was against the law to carry film-reels on public transport due to the immense fire-hazard. The very word ‘Cinema’ comes from the larger word ‘cinematograph’, an early form of projection camera. If the film produced wasn’t good enough, then the editor would take out a pair of scissors, slice off the bad film and splice the good bits of film together to make a complete reel – Anything not up to scratch literally ended up “…on the cutting-room floor”.

Despite technological shortcomings, films were being produced with amazing speed in Hollywood during the 1920s. Up to eight hundred a year during that decade alone. Most of them were short, one-reel flicker-shows, but the idea of the ‘feature length film’ was beginning to gain ground. The first feature-length film was actually produced in Australia in the early 1900s, and was about the famous Ned Kelly gang…Hollywood had a bit of catching up to do!

Due to the lack of audio, many early picture-houses featured a piano (or if they could afford it, an organ) to provide musical accompaniment. Most music was generic, written to provide a background to various filmic situations – Love-scenes, dramatic fights, light relaxing music for summer days, scary, dramatic music for stormy weather or horror films…Only the really big-budget films had musical scores written specifically for them. Cinema pianists had to be the best of the best, to accompany the film exactly in-sync for the music to work with what was being portrayed on screen. One of the most famous silent-film organists was the late Rosa Rio, who died in 2010. Playing the piano from the age of seven, her musical career ran for over a century (that’s right, 1909-2009). She started out as a silent-film pianist, then she moved to radio, then to television, providing some of the most famous theme-tunes ever known, such as the haunting and slow organ music that accompanied the opening of every episode of the famous radio-program, ‘The Shadow’.

Rosa Rio, silent film organist, 1934

The Birth of Talkies

“Talkies”, so-called because the actors could be heard to talk, came out in the late 1920s, when film studios figured out how to successfully synchronise recorded sound with moving pictures. Many people will tell you that the first talking picture was “The Jazz Singer” from 1927. This is both true, and untrue. It’s certainly got talking in it, but in many ways, it is still a silent film, complete with the exaggerated body-language and the intertitles that had existed since the earliest days of film production. I’ve seen the film myself and while it’s certainly a great story – I don’t know that I’d call it a modern, audio-synchronised film as we would know it today.

Talkies were a watershed of an invention. Some people loved them…Others hated them! Many silent-film actors were put out of work because they just didn’t understand the new technology and were unable to adapt to it. Charlie Chaplin was one of the lucky few that did…although he held off making his first ‘talkie’ film until well into the 1930s, by which time silent films were fast becoming ancient history. It was because of the invention of talkies that one of the most famous pieces of filmmaking equipment was created…the clapper-board:

The clapperboard was used to help the filmmakers. By showing the film, but most importantly, the act, scene and take-numbers, they could accurately synchronise motion with sound, from the ‘clack!’ that started each reel. It was invented in the late 1920s in Melbourne, Australia.

The Hollywood Sign

The most famous thing about Hollywood is of course, the Hollywood Sign. It was created in 1923 as a real-estate advertisement and originally read “HOLLYWOODLAND” and was lit up by thousands of lightbulbs at night. Only designed to be up there for a few months, no thought was given to its preservation and it was allowed to deteriorate for over twenty years until it was partially renovated in 1949. By then, the weather had damaged the sign so badly that the decision was made to remove the last four letters, leaving simply ‘HOLLYWOOD’.

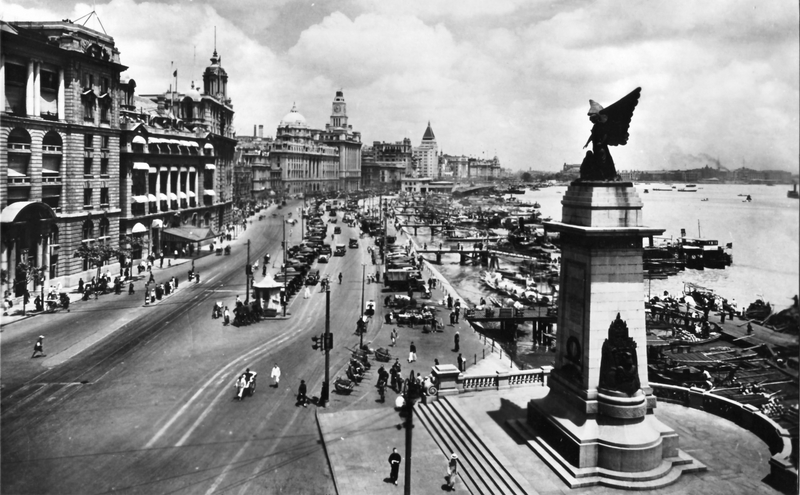

The original Hollywoodland sign, photographed here in the 1930s

The original sign from 1923 doesn’t exist anymore. The one that we see today was what replaced the original sign in the 1970s. Continued exposure to the elements had necessitated the sign’s complete replacement in 1978.

Pre-Code Hollywood

A lot of people like to think of old Hollywood films as weak, soppy, exaggerated and overacted. And perhaps they are. But that’s only because of the intense censorship that existed in Hollywood at the time. Any Hollywood films made before 1934 (especially those made between 1927-1934) are classed as “Pre-Code” films. These films were full of sex, violence, blood, rough fist-fights and even homosexuality. It was during this time that many of the great gangster films were made, such as the infamous ‘Scarface’ and ‘Little Caesar’. Free from creative restriction, filmmakers and actors let themselves loose on the camera and film-set, shooting what they wished.

It was in 1934 that all this fun and joy had to end. It was dangerous. It was immoral. It was offensive to women, children, civilised men and to President Roosevelt’s pet dog (…maybe. The dog could not be reached for comment). Religious and morality groups spoke out against the percieved ‘immorality’ of these films, and demanded that the government take steps to clean up the act of the American motion-picture industry. As a result, a strict list of rules was created. These rules clearly stated, or strongly suggested that, among other things…

– Sexual innuendo was to be illegal. No nudity. No ladies lifting their skirts. No sex-scenes of any kind.

– Criminal films were to be strictly censored. It would be better if films did not show scenes of robbery, theft, murder, brawling…firearms, safecracking, malicious demolition of railroads or buildings…the list goes on and on. No wonder all the best gangster-films were made before 1934!!

– Profanity of any kind was illegal. It’s for this reason that Clark Gable shocked everyone in 1939 with his infamous line “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn!”.

– Death wasn’t allowed to be gory or excessively violent.

The damage that the ‘Hays Code’ as it was called, did to the American film industry was catastrophic. Many actors were furious and felt that their creativity was being severely impeded. One of the most famous of these was the actress Mae West. Famous for her saucy double entendres and generous breasts, she faced almost complete ruin thanks to the restrictions placed on her by the Code. Many movies from earlier years, mostly those from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s were heavily edited to comply with the new censorship laws, the result being that many classic films are now only available in their post-code states. In some cases, films were destroyed outright because they didn’t comply with the rules of the Hays Code.

One of the most famous and most obvious examples of the Hays Code in effect is in fight-scenes. They almost always take place at night and always in the dark, with the lights turned off and only turned on again when the fight is over. On the surface it makes no sense, because it’s almost impossible to film a fistfight in the dark, but this was done deliberately so that the audience wouldn’t see the violence portrayed on screen and children wouldn’t be desensitised to it. Another example comes from the 1950s Stanley Kubrick film “Paths of Glory”. A film set during the First World War, soldiers killed in combat merely flop over dead onscreen (regardless of actual manner of death). Compare this with the jarring introduction of Stephen Spielberg’s famous film ‘Saving Private Ryan’ which portrayed the full horror of a beachfront assault.

The Code couldn’t last. By the 1940s it was already being eroded as people complained that, while the Code did have its good points (needless or pointless violence and sex was removed from films, for example), it increasingly caused problems for filmmmakers who were unable to shoot particular scenes. The Code died a slow death, though. It wasn’t until the mid 1960s that it was finally abandoned, to be replaced by the Motion Picture Association of America’s rating-system that we know today (“G”, “PG”, “PG 13+”, “R” and “NC-17”) which allowed films of all kinds to be created, and merely advised people of their content prior to watching them.

The full text of the Hays Code of 1930 may be found in the ‘Article Sources’ page of this blog.

The Big Studios

With the arrival of talkies, filmmaking really took off. The 1930s to the 1950s is considered the “Golden Age of Hollywood”. In this roughly twenty-to-thirty year gap, some of the most famous films ever, were shot in Hollywood. Classics like “Gone with the Wind”, “The Wizard of Oz”, the ‘Dick Tracy’ films, the classic ‘Sherlock Holmes’ films starring Basil Rathbone, “San Francisco” starring Clark Gable and many famous Hitchcock films, such as “North by Northwest” in 1959.

Hundreds of films were produced every year by big movie-studios. Called the ‘studio system’, the big-name filmmakers produced their films entirely on their own lots. They also controlled film distribution-rights as well as some of the better cinemas in town, which meant that they could make more money. Some of the big studios have survived into the 21st century. These include…

– MGM (“Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer”)

– Paramount Pictures.

– Warner Brothers.

– RKO Radio Pictures.

– Fox Film Corporation (later “20th Century Fox”).

The only one of these not around today is RKO Radio Pictures. Famous for films such as “King Kong” (which saved the company from bankruptcy in 1933), the company folded in 1959.

Before the age of television, Hollywood was pumping out hundreds of films a year, dozens of films a month. Some films made it big, some have faded into history. In the 1930s and 40s, Hollywood films were extremely popular – for just a few cents you could buy a ticket and forget your troubles for a couple of hours and not worry about the Depression or the War that was going on around you. Hollywood boomed in this era for that reason. With so many films being made, less emphasis was put on films to make them a hit and fewer people worried if a film was a flop – there was nothing to compete against so it probably didn’t matter. Some films did make it big – “Casablanca”, “San Francisco”, “The Big Sleep” and “Twelve Angry Men” to name but a few.

An antique Bell & Howell movie-camera from 1933. An identical one was used in the Peter Jackson remake of ‘King Kong’. Cameras similar to this were common during the Golden Age of Hollywood

Hollywood During the 30s and 40s

Although Hollywood began to take off during the 1920s, the 1930s and 40s nearly killed it. The Depression could have shut the movie-making industry down, just as it killed off nearly everything else in the United States, but strong ticket-sales saved the various studios then in operation, from going bankrupt. Buying a film-ticket for a few cents was the only way that most Depression-era people had of escaping their misery, and they bought millions of them. ‘King Kong’, released in 1933, was wholly responsible for saving RKO from bankruptcy during the worst years of the Depression, when one in four Americans were out of work and unemployment was in the millions.

In the Second World War, Hollywood helped produce propaganda films and documentaries for the war-effort. While some may be considered insensitive today, they were undeniably funny and were aimed at boosting Allied morale and reminding Americans why they should fight a war which some of them thought, wasn’t theirs to bother about. Hollywood even produced training-films for the U.S. Army to better educate soldiers. They produced instructional films for soldiers as well, in the shape of the famous “SNAFU” cartoon-shorts. They were supposed to be followed by additional cartoon-series with SNAFU’s cousin TARFU and FUBAR, but these last two weren’t produced due to the war’s end. Because they were aimed at soldiers, these instructional cartoons were considerably more adult than other material Hollywood produced during the same-era…SNAFU, TARFU and FUBAR are all military acronyms. Respectively, they stood for: “Situation Normal: All Fucked Up”, “Totally and Royally Fucked Up” and “Fucked up Beyond All Recognition”.

The End of the Age

The ‘Golden Age of Hollywood’ ended in the 1950s and 60s. The collapse of the U.S. Government’s ‘Hays Code’ meant that filmmakers were able to produce drastically different types of films, no longer restrained by what some people thought were over-the-top restrictions and regulations. Although invented in the 1920s, it wasn’t until the 1950s that television finally took off and by the 1960s, was really spreading around the world. Some people feared that television would put the movie-making industry and cinemas out of business, but this fear proved groundless. What television did do was change the way Hollywood operated and affected the kinds of films they made. With fewer people going to the cinema, the number of films made dropped significantly, to about four hundred a year today.

“Hooray for Hollywood”?

If you’re wondering about the title of this article, it’s taken from the 1937 song “Hooray for Hollywood”, a piece of music written for the film ‘Hollywood Hotel’. It’s widely considered the official “theme-song” of Hollywood and is sometimes heard at awards ceremonies (even those not held in the United States!) The lyrics, largely forgotten today, celebrate the golden age of American filmmaking. They can be confusing and hard to understand today because they use many outdated slang-words, mention actors or actresses who have since passed away and refer to technology long obsolete.