What do I like about history? Is it all the fancy old stuff? Is it the facts and figures? Is it the new inventions that were popping up all over the place?

Yes. Of course. But if I had to pick one reason for loving history, it’s because of all the stories that you get to hear about and learn about and pass on to others.

Like the story within this article.

This article will cover one of the lesser-known stories of the Second World War. Everyone knows all the big stories. The Blitz, the Battle of Normandy, the Invasion of Russia, the Fall of France, the Attack on Pearl Harbor, the Dam Busters and the heroics of Oskar Schindler, but in and amongst all these wonderful and amazing stories are the ones that people forget about, or which they can’t imagine ever happened, because they just seem too weird and strange and out-of-place.

This is one of those stories.

This is a story about the Jews. It’s about the Jews and the Second World War. It’s also about a city. In fact, it’s about one of the very few cities in the world which helped to save Jews from Nazi persecution during the years leading up to the outbreak of war with Germany in 1939, taking in thousands of refugees from the hell of Europe when no other city in the world would bother to open its gates. This city is not London, New York, San Francisco, Melbourne, Singapore, Hong Kong, Taipei, Belfast or Boston. It’s not Sydney or Tokyo or Havana. In fact it’s none of the cities that you would ever imagine that persecuted German Jews would ever think of going to.

In English, its name literally means “On the Sea”. In its native tongue, this city is called…

Shanghai.

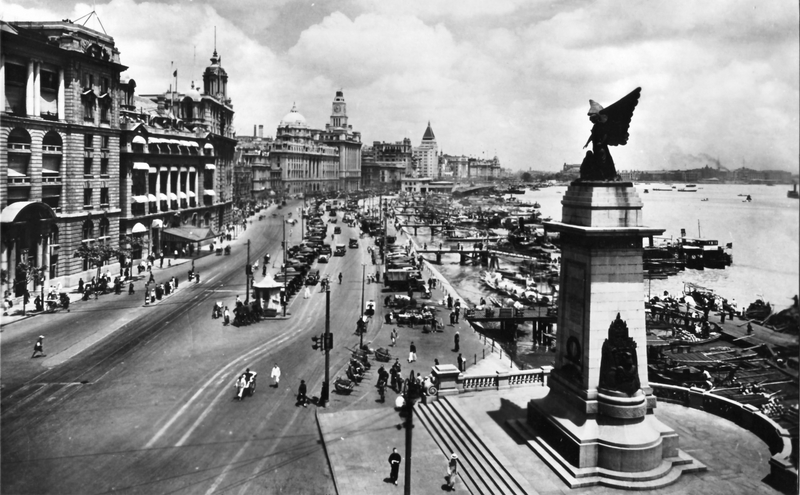

“The Bund” on the waterfront of Shanghai’s International Settlement Zone, Shanghai, China. 1928

Escaping the Nazis

Of all the places in the world to flee to, so as to escape from oppression, hardship and persecution, one of the last places on earth that you’d think the Jews would pick is China. Not because it wasn’t welcoming or accepting of Western Jews or because of language-barriers or cultural clashes or anything else, but simply because it was such a different place from any other country in the world at the time. Why on earth would escaping European Jews from Poland, Germany, Austria and France (among other European countries) wish to flee to China, a country that was so incredibly alien to them?

The truth was, they had no choice.

In 1933, Hitler and the Nazis came to power in Germany. Although at first things seemed normal, by 1935, life for German Jews became increasingly restricted and more dangerous, with the passing of the “Nuremberg Laws“, that controlled, prohibited and monitored an increasing number of Jewish activities and freedoms. Everything from where Jews could shop, where they could go in public, what they could own, when they could go out, whether or not they could use public transport, whether they could travel, use public institutions such as swimming-pools, cinemas and theatres and even what kinds of jobs they could have. Jews were banned from legal occupations, educational occupations and military occupations. Jewish lawyers, teachers, university lecturers and soldiers were all kicked out of the German companies or organisations that they worked for.

Life for Jews in Germany became more and more dangerous as the 1930s progressed and while some believed that this was a passing thing and that sooner or later all this antisemitic fervor would die down, others saw the writing on the wall. They were convinced that it was not safe for them to remain in Germany anymore, and that they had to get out.

But leaving Germany was not easy. You needed passports, money, travel-permits, tickets and visas to move around. If you were patient or resourceful or rich enough to beg, borrow, bribe, buy or steal these documents, you might be able to escape to another country such as France or Poland or Italy. However, other people were so scared that they wanted to leave Europe altogether.

Leaving Europe in the 1930s was fraught with all kinds of diplomatic and foreign-policy nightmares. In the 1920s and 30s, many countries had ‘immigration quotas’. A country would only allow…so many Jews…so many Chinese…so many English…so many Americans…so many Germans…to migrate to their shores each year. And once that quota was met, the gates were closed and all ships were turned away. The quotas were often deliberately kept small. Only a few thousand people from each category were allowed in. For those who were lucky enough, they could book a steamship passage from Germany to England or to America or even Australia and take comfort in that in a few weeks, they would be out of the reach of the Nazis.

But those were only the people who were lucky enough to find themselves within the government immigration-quotas. What was to become of the hundreds of thousands of other Jews who were desperate to escape from Nazi Germany? There was almost nowhere else to go. Once the quotas were full, German Jews would have to wait a whole year before they could get another bid at sailing to England, America, Australia or any other country of safety again. And by then, it might be too late.

In sheer desperation, German Jews looked to the East. To Asia. To countries in the Pacific which would take them and accept them and give them at least a chance of escaping from the Nazis. One of the few places that opened its gates was the Chinese port city…of Shanghai.

China in the 1930s

Perhaps one reason why people might not think of China as a safe port for persecuted German Jews in the 1930s is because of the fact that at the time, China was fighting its own war with Japan. Not the Second World War, but the Second Sino-Japanese War, which lasted from July, 1937 until September of 1945. In time, Japan would become an ally of Germany. So why go there?

The reason for wanting to go to China was because the Japanese were there.

In comparison to the super-restrictive world of Nazi Germany, where travel-permits and other essential documents were almost impossible to find, in China, travel-documents were practically ignored. Passport-control in the port city of Shanghai was non-existent, partially because of the huge, diplomatic mess that already existed in Shanghai at the time.

During the 19th century, China had been rocked by foreign wars. The Opium Wars had forced China to open its gates to the Western powers, something that China was very reluctant to do. The Chinese Imperial Government saw itself as being the head of a country which was the head of the Asian world and which would answer to no other power. However, the British, French, American and other European powers wanted in on China. They wanted Chinese resources and they wanted Chinese products. This resulted in the Treaty of Nanking. The Treaty covered many things, but the main thing it covered was international trade. Foreign Powers (mostly the British) wanted the Chinese government to open up their port cities and give the British the power to trade within China and do business with whoever they wished.

One of these port cities…was Shanghai.

A map of what Shanghai looked like in 1931

Although the reigning Qing Government was opposed to this, by the early 20th century when Imperial China had collapsed, to be replaced by a capitalist, republican Chinese government, the city of Shanghai was booming.

In accordance with the Treaty of Nanking, within Shanghai were various sectors in which foreign powers could trade. There was the Chinese Sector (Old Shanghai), there was the French Sector, American Sector, British, German and even the Japanese sector. In July of 1937, the Chinese lost the authority of passport control for people entering Shanghai due to the Japanese invasion of China and the occupation of Shanghai. The foreign powers didn’t want to control passports because if the Western powers could control passports, then the invading Japanese would fight for the ability to take over passport control, if that happened, then all hell would break loose. As a result, no country or organisation at all controlled passports into Shanghai. With such a collapse of travel-regulations…

It was the perfect place for German Jews to try and escape to.

Escaping to Shanghai

With almost every other major port city in the world shutting its gates to German Jewish refugees in the 1930s, Shanghai was the last place on earth (almost literally) that persecuted Jews could hope to receive any kind of welcome at all. The chaos of the Second Sino-Japanese War meant that the conventional regulations that controlled immigration to the city of Shanghai had all but disappeared. With passports for Jews being either confiscated or almost impossible to obtain, the lack of any passport control at all made Shanghai the perfect destination for those trying to escape Nazi persecution.

Of course, the journey to Shanghai wasn’t all smooth sailing. Jews still had to get out of Germany! Those that were lucky enough managed to catch trains or drove or even walked from Germany south to Italy. From there, they would board Asian ocean-liners bound for the Far East. The voyage to China was a long one. From Italy across the Mediterranean Sea, through the Suez Canal, across the Indian Ocean and then northeast into the Pacific and then West to the Port of Shanghai, a journey that took a month by steamship. Perhaps ironically, the Jews escaped Germany on ships operated by the eventual German ally, Japan. Two of the ships were the S.S. Hakusan Maru and the S.S. Kashima Maru.

The S.S. Hakusan Maru

The S.S. Kashima Maru

With all other ports closed to them, Jews began to realise just what a golden opportunity Shanghai had become. It was probably the biggest stroke of good luck they ever had before the War. It was gold that they would have to dig for and good luck that they would have to grab they horns, but it was there for them nonetheless. If they could get there in time, that is. But a surprising number of Jewish refugees did catch onto this opportunity and the sheer number of Jews that actually managed to make it to Shanghai is quite staggering. Between 1937 and December of 1941, over twenty thousand Jews, mostly from Germany, managed to book passages on Shanghai-bound ships and sail out of the reach of the clutches of the Nazis to the relative safety of China. The majority of them managed to get Visas from anti-Nazi consular officials and underground resistence-fighters. Ships sailed regularly from Italy to China, ferrying thousands of Jews to the safety of the Port of Shanghai.

Arriving and Surviving in China

Any Jews arriving in China and expecting a fanfare welcome were to be sorely disappointed. Although the disruption caused by the Japanese meant that it was much easier to get to Shanghai and therefore, safety, once they were there, the German Jewish refugees were more or less on their own.

The City of Shanghai was divided into sectors centered around the Huangpu River. To the west of the river where it turned 90-degrees and headed towards the East China Sea, was Old Shanghai, the Chinese sector, and the French Sector. North of the French sector and the north bank of the Huangpu River was the International Settlement Zone. The Jews were dreaming if they could flee from Germany and settle in these busier, more affluent parts of the “Oriental Paris” as Shanghai was called. In fact, the Jews were forced to live in a run-down, working-class part of Shanghai, east of the International Settlement Zone, a desperate slum called Hongkew (“Hongkou” in Chinese).

Life in Shanghai was incredibly hard. Food was scarce, jobs were hard to come by and sanitation and comfortable housing were mere pipe-dreams. But the Jews survived. Despite living in the Hongkew sector of Shanghai, they survived. By pulling together and working together and supporting each other, they survived.

While some Jewish refugees did manage to find work in Shanghai and were therefore able to survive and in some cases, make life relatively comfortable for themselves and their families, the majority of the twenty thousand Jews were reliant on the charity provided by wealthy Jewish families already well-established in Shanghai, or from American Jewish aid agencies. The most prominent of these was the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (commonly called the JDC). Despite the disruptions of the Japanese, wealthier Jews supported the poorer Jews and aid organisations helped those who were unable to help themselves. In one way or another, they survived.

The impact of the Jews on the Chinese population was probably negligable. The Chinese, already driven into hardship by the Japanese already, barely noticed the Jews. But when they did, relations were tolerant and polite. Perhaps because the Chinese were already suffering, they sympathised with the Jews. They did business with the Jews and the Jews did business with the Chinese. For a few years, although life was hard…things seemed to be going alright.

The Shanghai Ghetto

Although life was very hard for the Jewish refugees living in Shanghai, even though they had to put up with shortages of food, money, clothing, proper housing, even though they had to worry about the Huangpu River flooding every time it rained, even though they were disgusted by the lack of indoor sanitation, even though the Hongkew Sector was patrolled regularly by Japanese soldiers, they survived. And they also considered themselves damn fortunate to be in China. By 1939, war had broken out in Europe and further transports of escaping Jews from Europe to China pretty much dried up overnight. The Jews living in Shanghai knew that they were lucky to be living there and were lucky to be running and living their own lives. If only they’d known what was happening to their relatives in Europe, they would’ve thought themselves luckier still.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing in Shanghai, either. From 1937 to 1941, life in the Shanghai slums was filthy, depressing and riddled with disease and hunger…but at least the Jews were safe. That was all about to change.

In December of 1941, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Within days, Great Britain and America had declared war on Japan. In Shanghai, the Jewish situation went from bad to worse.

Already struggling to get by and just keeping their heads above the water, the Jews were dealt an even harder blow. Jews living in Shanghai who were British subjects were now considered enemies. They were rounded up and sent to concentration-camps. These British Jews were the ones with all the money. With them went all their charitable contributions to the refugee Jews of Europe. But with the declarations of war against Japan, American Jews in Shanghai also became the enemy. The JDC almost ceased operation altogether, if not for a stroke of luck. Because America was now an official enemy of Japan, the JDC could no longer rely on American funds and donations coming from the United States to keep it operating. With the wealthy Shanghai Jews, those who were British subjects, now incacerated, the JDC turned to Shanghai’s other pre-war Jewish community, a collection of Russian Jews who fled to Shanghai during the Russian Revolution of 1917, for donations and funds. Although Shanghai’s Russian Jewish community was not as wealthy or as prominent as the British Jewish community, they did nevertheless, manage to keep the JDC running so that it could continue is charitable work.

Excerpt from the Shanghai Herald newspaper, dated February 18th, stating that all “Stateless Refugees” (which included Jews) had to move to their own sector within the Shanghai distict of Hongkew, by the 18th of May, 1943

Just like in Europe, though, the Jews in Shanghai were forced into a ghetto. Officially, it was called the “Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees”, but over time, people just called it the “Shanghai Ghetto”. It was a tiny place just a square mile in area, into which twenty thousand Jews were crammed in.

The Shanghai Ghetto, 1943

As unpleasant as this was, the Shanghai Ghetto differed from comparable European Jewish World-War-Two ghettos in many ways. To begin with, the JDC continued to provide charity to the poorest of their community. The Ghetto was not walled in like those in Poland and Germany, and the Chinese already resident in the area of Hongkew designated as the ghetto did not bother to leave. So the Jews were not totally isolated as they were in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Because the Ghetto was not walled, the Jews were able, more or less, to go where they wanted. They required special passes and permits to do this (issued by the Japanese), but they could still travel outside the ghetto, but only for work. Some Jews would take the opporunity of their out-of-ghetto trips to buy essential supplies for their families, or to buy things that they could sell for a profit (meagre as it was) in the ghetto and get some more money to feed their families.

Life in the ghetto grew increasingly harsh as the years wore on. A lack of coal and wood meant that there was a real risk of freezing to death in winter. Food was always scarce and what food there was usually had to be cleaned and prepared specially before you could eat it, since it was often the worst, cheapest food available.

The United States Army Air Force started air-raids on Shanghai in 1944. For the past few years they had been driving the Japanese back through their Pacific island-hopping campaign and they were now determined to flush the Japanese out of China. Shanghai was hit heavily during the raids, especially on the 17th of July, 1945, when American B-29 bombers attacked Hongkew specifically. A number of Jews and Chinese were injured or killed during this and subsequent raids on Shanghai, although the number of Chinese casualties was almost always significantly larger than those of the Jewish community.

Leaving Shanghai

Liberation for the Jews came in September of 1945 when the Japanese surrendered and Chinese forces entered the city and declared it safe. Soon after, aid agencies such as the International Red Cross entered the city to give aid to civilians, including the Jewish refugees. Desperate to know what happened to their families back in Europe, many Jews turned to the Red Cross. The Red Cross had come to Shanghai bearing news of the Holocaust, but they also brought survivor-lists for the Shanghai Jews to read, information that probably helped them make up their minds pretty quickly about what they wanted to do with their lives. Many Jews living in Shanghai during the War felt a significant level of survivor-guilt at the end of the conflict, wondering why they had managed to survive the holocaust in the relative safety of Shanghai, while entire families, all their friends and all their relatives had been killed.

Compared with the ghettos of Europe, the concentration-camps, the death-camps, the roundups, the starvation, the gassings and the horrible uncertainty that nothing was certain at all…Shanghai was like paradise. In the years to come, the Chinese Civil War would drive many Jews away. Thankful to have survived the War, the roughly twenty thousand Jews who had called Shanghai their home between 1937 and 1945 boarded ships for Western countries such as Australia, Canada and the United States.

By the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949 there were only about a hundred Jews still living in Shanghai, however for the roughly 19,000 Jews that survived the War thanks to the ability to take refuge in this Oriental Paris, Shanghai would always hold a special place in their hearts, and indeed, in the hearts of Jewish people all over the world.