Mental illness is a horrifying thing. It has had a long, long, long, troubled past, full of superstition, horror, misunderstanding, experimentation, mistreatment, pain, suffering, abuse and conjecture. It’s the stuff of horror movies like “House on Haunted Hill”. For centuries, the mad and insane have suffered, some in silence…others, not so much.

This is the history of madness. A look at how mental illness has been viewed throughout the centuries, and how people attempted to treat it, control it and cure it.

The Nature of Madness

Mental illness has been around for as long as mankind, and for as long as it has existed, there have been explanations for it, reasons for it, cures and treatments for it, whether they be right, wrong, effective, ineffective or just plain crazy!

How far mental illness can be traced is totally unknown. Only since the dawn of the written word and reliable records can we can even begin to guess at how many centuries mental illnesses have existed for, or how far back certain specific illnesses can be traced.

The Cause of Insanity

People have been trying to figure out what caused mental illnesses for as long as they’ve been around. One of the earliest explanations was that it was related to the movements, phases and positions of the Moon. The Latin word ‘Luna’, or ‘Moon’, has given us the words ‘lunacy’ and ‘lunatic’.

Other common beliefs included posession by devils, demons, evil spirits…or that the person was a witch. In the last case, the most expedient ‘cure’ involved a large stake, lots of wood and a burning torch. To deal with ‘evil spirits’ or ‘demons’, the most common ‘cures’ were either an exorcism, or a terrifying operation called a trephination or a trepanning.

Trepanning was the practice of gaining access to the brain by means of making an incision in the organ’s outer casing.

In other words…drilling a hole in your head.

Trepanning is still practiced today, but its benefits (relieving pressure on a damaged and swelling brain) are much better understood now, than they were back in the Middle Ages, when this treatment was used to ‘cure’ insanity and release a person’s demons from their soul.

Trepanning was carried out using one of a variety of drilling or boring tools…such as this delightful instrument:

Stay very still and don’t sneeze…

The procedure was typically carried out in the following manner:

1. The patient was seated (or laid) on a chair or bed and secured in-place (either with straps or with the aid of surgeon’s assistants).

2. The head (or the necessary portion of it), was shaved smooth.

3. A Y-shaped cut was made into the skin, and the skin then peeled back.

4. A mark was made on the bare skull and the drill placed thereon.

5. Start drilling.

Oh…and if you’re the patient, you get the unique firsthand experience of watching everything that happens. Because there’s no anesthetics.

Trepanning was used to treat more regular health-issues, such as migraines, headaches and so-forth, but it was most famously used for the treatment of mental illness.

As folklore, superstition and religion slowly gave way to reason, logic, science and medicine towards the 1700s, a greater understanding was sought of the lunatic. What caused someone to go mad, what they should do with him, how he should be treated and what might happen to him. In Georgian England, the answer lay in one word.

Bedlam.

Or, as it is properly called, the Bethlehem Royal Hospital.

The Bethlehem Royal Hospital, or as it was more commonly called,Bedlam, was…and is (it’s still around today!)…the most famous mental hospital in the world. It’s also one of the oldest. Its existence goes all the way back to the early 14th century, when it was established in 1330.

Like Bedlam

The Royal Bethlehem Hospital, or Bedlam, was, is, and remains, the world’s most famous mental hospital. Even today, a phrase survives. A place that is rowdy, noisy, out of control and crowded with people is described to be “like Bedlam”. As indeed, the hospital was, during its most famous and notorious period, in the 1700s.

Previous to this time, the inhabitants of Bedlam were referred to as ‘inmates’, as if it was a prison for the mentally ill. In 1700, the inhabitants (also nicknamed ‘Bedlamites’) were called ‘patients’ for the first time. Between 1725-1734, ‘Curable’ and ‘Incurable’ wards were opened, where patients were supposedly housed accordingly. But despite the apparent show of progress, Bedlam was a hellhole.

In the 1500s and 1600s, the hospital was filthy and patient-care was almost nonexistent. Barely anything changed by the Georgian era. Patients were often chained to walls, locked in filthy cells or subjected to brutal ‘treatments’, such as ‘The Chair’.

It didn’t DO anything. You were strapped in an armchair. Tied down. Secured. Then the chair was hoisted up into the air and spun around…and around…and around…and around…and around…It was supposed to punish you for being ‘mad’, hoping that you would repent of your wicked and sinful ways and be an upstanding citizen once more.

Unsurprisingly…it didn’t work. Unless the purpose of the treatment was to make you expel your lunch, that is.

For almost the entirety of the 1700s, Bedlam was a popular tourist-attraction in London. It was common for the wealthy, upwardly mobile classes of British society to take in the sights…and one of them was a trip to the Bedlam Hospital, where, for a small fee, you could be granted admission to the wards. Here, you could view the lunatics and bedlamites and if you wished, you could poke them through the bars of their cells with your walking-stick to watch their reactions. It’s fun, trust me. Bring the kiddies…It should always be a family outing, a trip to a lunatic asylum.

One of the most famous depictions of the Bedlam Hospital is the final painting in a series by Georgian artist, William Hogarth, titled ‘A Rake’s Progress’. Painted in the early 1730s, this is what the notorious lunatic asylum looked like in the 18th century

One of the most famous depictions of the Bedlam Hospital is the final painting in a series by Georgian artist, William Hogarth, titled ‘A Rake’s Progress’. Painted in the early 1730s, this is what the notorious lunatic asylum looked like in the 18th century

By the turn of the century and the coming of the Victorian era, views on mental health were (gradually) changing and conditions at Bedlam did eventually improve. Government inquiries, reports and investigations brought to light the shocking conditions inside Bedlam and by the dawn of the 19th century, the regular tours had died away after surviving as a London fixture for nearly a century. The patients were given proper care and attention and the buildings improved.

The Maddest of them All

The most famous mad Georgian of them all was one of the kings who gave his name to the era. King George III. Up to 1788, he was a sharp, intelligent, learned man. He enjoyed science, technology, mechanics, farming and nature. He had a lovely and loving wife and a HUGE family (fifteen children in total!). But from then on, attacks of mental illness eventually robbed him of his senses. He died, blind, deaf and insane, locked in a tower in 1820. When his beloved wife, Queen Charlotte, died in 1818…nobody even bothered to tell him.

Mad Words

The Georgian era gave us a number of our most commonly-used words when describing mental illness – “Crazy”, and “Insane”, from Middle English meaning ‘cracked‘, and from the Latin word ‘Insanus‘ (‘Unhealthy’). ‘Psychiatry‘ as a discipline, was first practiced in 1808, when the word was coined by a German physician, Dr. Johann Christian Reil, from the Greek words meaning “Medical Treatment of the Mind”.

A Victorian View of Madness

Mental illness was not widely understood in Victorian times, but things were gradually improving. The Industrial Revolution made life faster. For the first time, things could truly be mass-produced.

And lunatic asylums were no exception. As a partial list, we have:

The Hanwell County Asylum (built 1830).

The Surrey County Asylum (built 1838).

The Royal Bethlehem Hospital (extended, 1837).

The City of London Lunatic Asylum (opened 1866).

Guy’s Hospital (Lunatic Ward, opened 1844).

The list goes on. And this is just in England.

Thanks largely to reforms at the turn of the century, the Victorian-era lunatic was handled with much greater care, but probably with just as much misunderstanding. Causes, and treatments for, mental illnesses…and indeed, the distinctions between one illness and another…were still very much muddled up. But progress was…slowly…being made.

The increase in number, and size, of asylums and hospitals around the world, as well as the number of patients, caused problems. Although chaining patients up was no longer an acceptable method of restraint, something was needed to stop patients from hurting themselves. If they couldn’t be drugged up with heroin, opium, laudanum and morphine (common Victorian drugs for calming someone down!), then they had to be rendered a negligible force in some other manner.

Its existence predates the Victorian era, but the straightjacket was the most common method.

Invented in 1790 in France, it was first used at the Bicetre Hospital in the southern suburbs of Paris. Bicetre was not a place where you wanted lunatics to run wild. It wasn’t just a hospital. It was a lunatic asylum, a prison and an orphanage as well!

The straightjacket was used regularly on mentally ill patients, even before the Victorian era. It was the only way that badly understaffed mental asylums could control all their patients at once. But a straightjacket isn’t supposed to be worn for a long period of time (restricting the limbs like that causes blood-clots and other nasty things…perhaps why Houdini wanted to break out of them so often). Bicetre Hospital was one of the first mental asylums, along with Bedlam, to introduce humane treatment methods for the mentally ill during the sweeping social and moral reforms that spread around Europe and the United Kingdom in the 1790s.

Research and theorising into the causes and possible treatments of mental illness started in earnest in the 1800s. Pioneers such as the famous Dr. Sigmund Freud, helped to guide the way. Freud, a Jewish German, fled Nazism in the 1930s and settled in England. He was on the hit-list of people to kill when the Germans invaded Britain. Fortunately for Freud, the Germans never invaded. And even if they had, it wouldn’t have done them any good. He died less than a month after the war started.

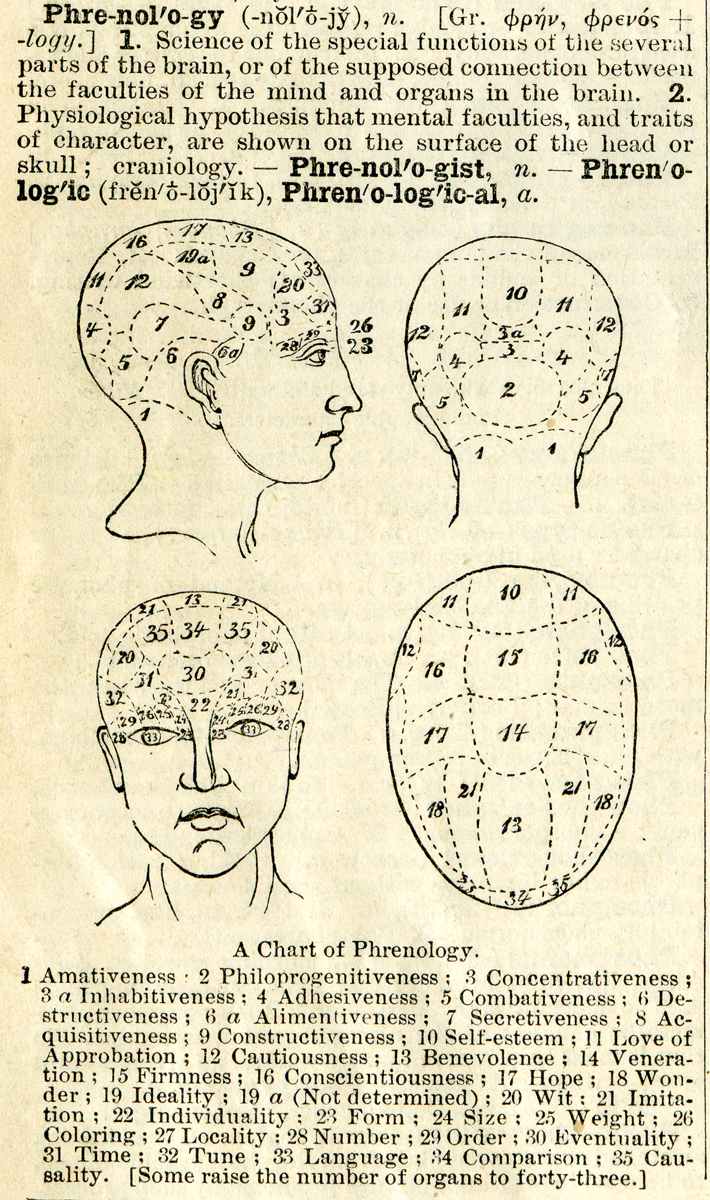

Phrenology

Perhaps you might have seen one of these?

These days, people buy them as paperweights, bookends, curiosities, dust-collectors, souveniers, decorations and hat-holders. But back in the Victorian era, these things were used to understand the brain.

Or something like that.

Shakespeare once wisely said that there was “no art to finding the mind’s construction in the face” (taken from ‘Macbeth‘, that was, in case you’re wondering). What the Bard meant was that it’s impossible to just look at someone, study their face, and then automatically know what’s going on inside their head.

Apparently, Victorian psychiatrists, doctors and psychologists…disagreed with the great playwright, because for most of the 19th century, phrenology held sway as the latest way to read and understand the workings of the human brain. And they were onto something!

…or not.

Phrenology has absolutely NO medical or scientific fact to back it up at all. It was dismissed as quackery by the end of the Victorian era and was declared to be of no practical benefit at all to the fields of medicine or science.

But what was phrenology?

The ‘Science’…so-called…of Phrenology, supposed that a person’s personality and traits, his mannerisms and so-forth, could be determined, or even predicted, by studying the shape of his head. If you’ve ever heard of ‘death-masks’ (masks or busts made of prisoner’s heads after their executions), they were made to try and study the heads (and minds) of the “criminal class”, as it was called in Victorian times. It was hoped that by studying the heads of criminals, their shapes, their foreheads, positions of ears and so-forth, a general list of ‘characteristics’ could be compiled, showing the public the typical face (and traits) of someone who is (or would become) a criminal.

Phrenology advocated the belief that the brain is divided into segments or “organs”. Each organ controlled an emotion, or trait, such as lust, hope, curiosity, aggressiveness, gentility, connivance and so-forth. It was believed that by examining the head of a person, you could map or determine his personality traits.

How?

Using a pair of phrenology calipers. They look like this:

You can stop sucking in your belly. They’re not for measuring body-fat.

The calipers were used to measure the head. By examining the size of the cranium (that’s fancy medical talk for your skull) the phrenologist could pick up on any abnormalities. He was looking for bumps or strange inconsistencies on your head. The positions of these bumps on your head were transferred to a chart (or to a phrenology head) where a number would be printed. The number corresponded with a trait, printed on an accompanying list. The bumps indicated the areas of the brain which were, supposedly, the most developed, and by extension, the personality traits that were most developed within your brain. This could determine your mood, temperment, likelihood for criminal behaviour, propensity towards violence, drunkenness, abusiveness, gaiety…all kinds of things! Fascinating!

Did it work?

No.

But it sure makes for interesting blog-material.

Phrenologists, as they were called, believed that each section of the brain controlled or housed a particular trait or emotion. You can see that here in this chart from 1895:

As you can see, phrenology didn’t last very long. This page is taken from a medical dictionary from 1895. Note the opening passage, that phrenology was the “…science of the special functions of the several parts of the brain, or of the supposed connection between the faculties of the mind and the organs of the brain…”.

Phrenology continued to linger long after it was dismissed as quackery by the respected medical community. It’s mentioned in “Dracula”, by Bram Stoker, and in numerous Sherlock Holmes stories by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Most notably, in “The Hound of the Baskervilles”, where Dr. James Mortimer confesses to an interest in phrenology…specifically, in a close examination of Holmes’s head! (“A cast of your skull, sir, until the original becomes available!”).

Want to know more about phrenology? Here’s an interesting and rather funny lecture given by Prof. John Strachan of Northumbria University in England. Enjoy!…Oh, this is just Part 1. If you want the rest, click on the video and it’ll take you to YouTube, where you can see the rest of it.

A New Century

The Great War of 1914 brought a new horror to the world of mental illness. It was given the title ‘Shell shock’, and was believed to be caused by the deterioration of the mental state, caused by the constant bombardment of artillery shells. The unrelenting stress thus created, it was believed, caused the affected person’s brain to just snap and blow a fuse.

It was in the first half of the 1900s that mental illnesses started getting names. Names like…

Catatonia (1874).

Schizophrenia (1908), from the Greek words that described a ‘split mind’.

Melancholia (An older term. ‘Depression’ today).

Bipolar Disorder (1957). Previously called ‘Manic Depression’ (1952) and ‘Circular Insanity’ (1854).

The 20th century also brought forth a new and terrifying treatment. One which had no sure and certain outcome and which could, if performed poorly (or performed at all!), leave the patient as a comatose vegetable. It was called the lobotomy.

Tinkering with what does the thinking, has been a fascination for centuries…just look at medieval trepanning. The lobotomy had its roots in late-Victorian scientific and medical experimentation. Great strides were being made in medicine during the turn of the 20th century. New drugs, new ways of doing things, new understanding, new technologies, were making the treatment of patients faster, safer, cleaner and more effective. Why not might the same be done for the human brain?

Mostly because the results were almost always a failure.

The Lobotomy

Ah, the lobotomy. Famous in horror films for turning monsters into angels, angels into monsters, and right-thinking people into perfect vegetables. But what is it?

The lobotomy as is most commonly thought of, was developed in the mid-1930s by Antonio Egas Moniz. In 1935 and 1936, Moniz ‘perfected’ one of the most controversial medical treatments in the history of medical treatments…and that’s saying a lot.

A lobotomy involves making two incisions (holes) in the front of the head and inserting a pair of blades into the brain, whereafter two cuts or slices are made into the frontal lobes (quarters) of the brain. This was supposed to alter the workings of the brain, calm the patient down and affect a remarkable change in personality.

…or not.

Some lobotomies were pulled off with relative success. Others became tragic failures. Because the lobotomy required small, precise slices or cuts into the brain, a small, precise instrument was used. Originally, that instrument was one of these:

The scientific term is an ‘orbitoclast’, but its similarity to the axes and picks used by mountain-climbers…

…caused people to call operations carried out with these instruments, ‘ice-pick lobotomies’.

Unsurprisingly, lobotomies were incredibly risky. Patients risked everything from death, paralysis, becoming a vegetable, losing their faculties, their ability to speak, see, function properly in society…It makes you wonder why such a treatment was ever devised in the first place! One of the most famous people to receive a lobotomy was a 12-year-old boy named Howard Dully. He’s still alive today. He was born in 1948. The lobotomy was performed on him with the permission of his parents. The damage was so severe that it took him his whole life for his brain to recover and for him to be able to function properly in society again. The lobotomy is such a mythical procedure in medicine today that he wrote a book about what it was like to have one, and the effects that it had on his life. His memoir is titled “My Lobotomy”.

The effects (and benefits, if any) of lobotomies were disputed almost immediately. Even by the 1940s, people were questioning whether or not this ‘procedure’ did anything useful at all. The Soviet Union made the performing of lobotomies illegal as early as 1950. By the 1970s, most other countries had followed suit. During the heyday of the lobotomy (the 1940s and 50s), up to 18,000 people were lobotomised in the United States alone.

Electroshock Treatment

Electroshock treatment or therapy dates back to 1938. It was devised by Italian psychiatrists Ugo Cerletti and Lucio Bini. Cerletti first experimented on animals, as all good scientists did back in those days, before moving onto human patients.

Why on earth would zapping someone with electricity be considered a good thing?

Cerletti believed so because he noted a remarkable change in his aggressive, mentally ill patients. Once zapped, aggressive patients tended to be calmer and more manageable. This was seen as a good thing (who wouldn’t agree?) and electroshock therapy was slowly introduced around the world, to treat those who had mental illnesses that caused them to be a danger to those around them, such as the “criminally insane”.

Electroshock therapy is obviously dangerous. Improper use of the therapy can lead to brain-damage, most notably, temporary or permanent memory-loss. It was often prescribed for violent criminals to calm them down, or for mentally ill patients who posed a physical danger to those around them. It’s still used today, to treat extreme depression, although in the 21st century, it’s much safer. It can still result in varying levels of memory-loss however…so if your doctor decides to prescribe you this treatment…think twice before saying ‘Yes’.

Looking for more Information?

Index of British Lunatic Asylums

Documentary Film: “Bedlam: The History of Bethlehem Hospital“.

History of the Bethlehem Royal Hospital

“What is a Lobotomy?” (WiseGeek.com)

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this blog. Thank you, I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your site?

On average every couple of weeks.

I have been absent for some time, but now I remember why I used to love this blog. Thank you, I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your site?

On average every couple of weeks.

I love this so much! So interesting and so accurate … I have just completed 8000 words on insanity in The Yellow Wallpaper for my degree and I found this article really inspiring! Thank you!

http://www.coramagazine.com

Hi Danielle. Thanks for reading. This article was very interesting for me to write, but also rather challenging, for obvious reasons – a lot of ground to cover!!

I’m glad you enjoyed it and that what I have here is on a level with your own writings 🙂

I love this so much! So interesting and so accurate … I have just completed 8000 words on insanity in The Yellow Wallpaper for my degree and I found this article really inspiring! Thank you!

http://www.coramagazine.com

Hi Danielle. Thanks for reading. This article was very interesting for me to write, but also rather challenging, for obvious reasons – a lot of ground to cover!!

I’m glad you enjoyed it and that what I have here is on a level with your own writings 🙂