During the Second World War, Britain worked tirelessly to undermine the German war-effort through epic feats of deception and cunning. Everything from the “Magic Gang” with Jasper Maskelyne, to General George Patton and the imaginary First United States Army Group (“FUSAG”), and the infamous “Operation Mincemeat”, where a dead body was dressed as an officer, filled with “sensitive documentation”, and then dumped off the Spanish coastline by a British submarine.

The majority of British deception-plans against the Nazis during the Second World War are well-known, and are rightly famous – the story of Operation Mincemeat was even turned into a major motion picture – in colour! But what is less well-known by the general public is the almost-forgotten German counter-effort against Britain, to pull off one of the greatest feats of forgery ever witnessed in human history.

This is the true story of the German attempt to produce millions upon millions of FAKE British banknotes during the Second World War, and to bring about the collapse of the British economy through hyperinflation. A story known as ‘Operation Bernhard’.

The Beginnings of Bernhard

The origins of Operation Bernhard came to fruition on the 18th of September, 1939, just a few days after the start of the Second World War, and the German invasion of Poland. The original idea was formulated by Arthur Nebe and Reinhard Heydrich, two architects of the famous “final solution” that would eventually lead to the Jewish Holocaust. The original plan was to produce hundreds of millions in forged, British banknotes and to distribute them throughout the United Kingdom. This would cause economic collapse, and destroy the world’s confidence in the Pound Sterling as a globally-accepted currency, which it was in the early 1900s.

Looking for any way to cripple the British war-effort, Hitler gave the plan his official approval, although for obvious reasons, it had to be kept as secret as possible…something which didn’t last very long, because before too much time had passed, Sir Michael Palairet, British Ambassador to Greece, had already been tipped off about the potential Nazi counterfeiting scheme, and forwarded full details, such as they were known at the time, to the government in Whitehall, and to the Bank of England, to be on the lookout for potential forgery of British currency. The warnings were heeded, even though the Bank of England believed that existing anti-counterfeiting measures already in place should be more than sufficient to thwart any potential forgery efforts.

Planning the Deception – Operation Andreas

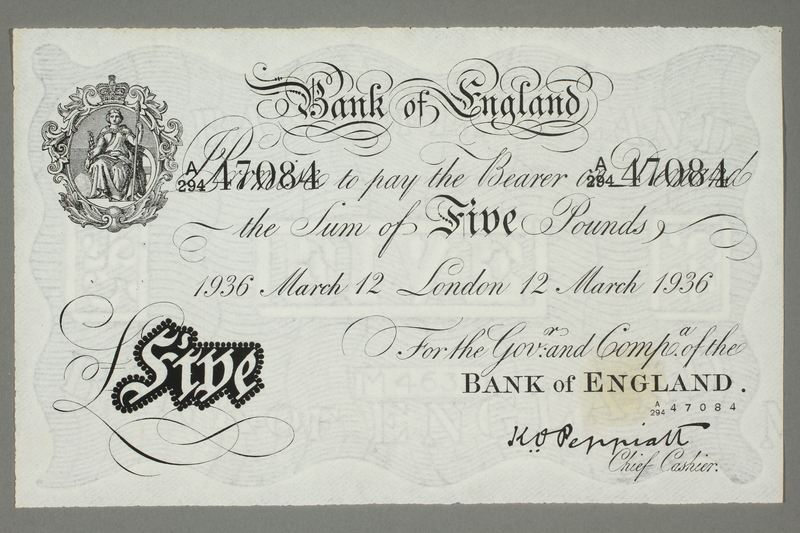

Operation Bernhard was comprised of several different elements, all of which had to be as perfect as possible for the plan to proceed. The first element of making the fake banknotes was, of course, to make the notepaper upon which the denominations of currency would be printed. This first stage of the plan was known as Operation Andreas, and involved finding the right combination of cloth rags and old paper and the right manufacturing processes to make the paper (or as close as possible) which British banknotes were printed on. Following steps were the engraving of the printing plates, the making of the ink, the forging of banknote serial numbers, etc.

The Germans were very confident in their ability to replicate British banknotes. The type of banknote (and the design printed upon it) used in the UK during WWII had been designed nearly 100 years before, in 1855. The banknotes were printed in black ink on large sheets of white paper – smaller sheets for five-pound notes, and larger sheets for 10, 20 and 50 pound notes.

To guard against forgery, every single plate used to print the notes had numerous little imperfections (up to 150 of them in total!) worked into the designs. These were usually imperceptible to the naked eye – but if they were perceived, then they would simply be passed off by the general public as minor printing-errors – the result of plate-wear, and of printing thousands of banknotes a day. Only bank officials would know what the marks and imperfections were, how many there were, their significance, and where these could be found on the various notes in circulations. As the imperfections were put down to wear-and-tear, the idea was that any forger making a banknote would try and make it even better than the original. A forged note with perfect printing would therefore stand out against a genuine note with small, but deliberate imperfections worked into the design.

Making the paper was surprisingly difficult, and the German forgers encountered several roadblocks along the way. The type of cloth and rags used, whether they’d been cleaned and bleached, how they were pulverised, how the paper was formed, and even the chemical composition of the water used to make the paper-mass, all had to be carefully examined and tested so that the notes looked perfect.

In the end, the decision was made to try and counterfeit five-pound notes. Being the most common notes in circulation, they were less likely to be scrutinised, and would more easily blend in with genuine British banknotes, becoming too widely dispersed too quickly for the Bank of England to pick up on the deceit until it was too late. As the war progressed, ten, twenty and even fifty-pound notes were also added to the list of fraudulent banknotes.

Early attempts at producing these forged five-pound notes proved highly problematic, and one of the biggest issues with trying to create accurate forgeries came from trying to reproduce the image of Britannia printed on every five-pound note. The engraving was so intricate that try as they might, a 100% accurate copy just wasn’t possible. It became so difficult that in 1942, the forgery plan was abandoned.

The Start of Operation Bernhard

While German forgers had given up trying to forge British banknotes, the German SS had not, and later in 1942, the plan was revived under the direction of Heinrich Himmler, and SS Major Bernhard Kruger – after whom the operation was named.

The original plan with the forged banknotes was to flood Britain with fake fivers so that confidence in the British Pound Sterling would collapse, or to cause hyperinflation. Spies and contacts had alerted the Bank of England about the possibility of this German plan as early as 1939, and first evidence of these forged notes started popping up in 1943. Fears that high-quality forged German notes could flood Britain, bringing down its economy started to rise.

Fortunately, this didn’t happen (or at least not on a large scale) because of a quirk of the Bank of England.

What none of the forgers or their controllers knew was that the Bank of England kept gigantic ledger books – some of them hundreds of years old – in which they laboriously recorded literally every single British banknote in circulation! See – every banknote issued by the Bank of England was a promissory note – a note which promised to pay the bearer five pounds – as in, five pounds sterling worth of gold or silver – upon presentation of the note.

To stop forgeries, every note had a serial number – this much, the Germans knew. What they did not know was that every single serial number, without exception – was recorded in a ledger before it was issued to the public. When a note was worn out or required replacement, it was returned to the bank. The serial number on the note was then crossed out of the ledger and the note was destroyed.

The problem was that several of the forged banknotes that the Germans produced had serial numbers on them which, when they were compared against the Bank of England ledgers – showed that they were fake! The genuine notes had already been turned in and canceled. So why were there suddenly notes showing up with identical, canceled numbers? They had to be fake! It sounds stupidly simple, but it really was that easy to find out which notes were forgeries. To catch the forgers out, the Bank of England had to do just one thing:

Stop making banknotes! Any other banknotes that were found in circulation would therefore obviously not be printed by the bank and could only be forgeries! So they did!

When they realised that their grand scheme for destroying the British economy had just gone out the window, Himmler and his S.S. confederates had to figure out some other use for their millions in forged fivers. This was when they got the idea that the banknotes could be used to fund the German war-effort. The pound sterling being a globally-accepted currency, it would be easy to pay for arms and materiel using the fake banknotes, and pass them off as genuine to unsuspecting arms-dealers or German allies, who, presumably, wouldn’t look too closely at the notes.

And this is exactly what happened.

To ensure that their plan was as foolproof as possible, Major Kruger started looking for more forgers, and eventually gathered up a group of Jewish prisoners from Auschwitz who had the necessary skills – engraving, artistry, calligraphy, and so-on, and set them up in their own barracks in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In the end, 140 men were chosen.

Because the prisoners were essential to the German war-effort, they were treated much better than other prisoners. Guards were forbidden to harass them, and they were given regular food, proper shelter and care. Of course the prisoners knew that all this relied on them producing the most perfect forgeries ever. This would be the only thing that kept them in the good graces of the SS.

Between 1942-1945, the prisoners (with their bases of operations constantly moving to keep them from escaping, or from being bombed by the allies) produced millions upon millions of pounds of British banknotes, along with a healthy dose of American dollars. These funds were then laundered and exchanged to secure Swiss Francs, genuine British banknotes, or genuine American dollars, with none of the other parties ever being any the wiser. In total, the prisoners were believed to have forged up to three hundred MILLION pounds!

The End of the Operation

Operation Bernhard came to a juddering halt in 1945 with the gradual collapse of Nazi Germany. The prisoners responsible for the forgeries were shifted continuously from place to place to try and keep them from escaping to allied lines. They were constantly broken up, reformed, separated and reunited. In the end, the SS decided that they were too much of a liability – that they knew too much – and would have to be “silenced”.

However, in typical German efficiency, the order given was that all the prisoners involved in the forgery operations had to be executed together – this way there was no chance of one or two of them escaping, or of there being any sorts of mix-ups. It was this strict adherence to this rule that actually saved all their lives!

In early May, 1945, the prisoners were moved yet again – this time to Ebensee Concentration Camp. The men had been broken up into three groups and were transported to the camp by truck separately. Two groups arrived, were sent into the camp, and then their guards fled to try and save their own necks. The order that the prisoners had to be killed together meant that they could not yet be executed – delays in transportation (the truck broke down!) meant that the third group had not yet arrived. Instead, they had to be marched to Ebensee, which took the better part of two days. This delay only increased the group’s survival.

When the third group did arrive, they too were simply dumped into the camp before their guards also fled from advancing U.S. troops. It would be impossible to pick out 100-odd specific prisoners from the thousands within the camp, so the SS guards who had escorted the forgers there simply didn’t bother. They had more important things to do – like try to get out of Europe! In this way, the prisoners were left in the camp on the 5th of May to await an uncertain future.

On the 6th of May, 1945, Ebensee camp was liberated by American soldiers, and against all the odds, the Jewish forgery prisoners had survived the entire war – and with an incredible story to tell!

The Fate of the Fake Fivers

So much for the fate of the forgers, but what about the forgeries?

When the war ended, Major Bernhard Kruger was arrested by the British, but they soon discovered that there wasn’t much that they could hold him on. While certainly illegal at any other time in history, forging an enemy’s currency in wartime was not actually a war crime! With nothing to hold him on, the British interrogated him extensively for two years during his denazification process, and then released him to French authorities, with whom he stayed with for one year. Some of the liberated forger-prisoners, after being interviewed by British officials, agreed to sign testimonies in Kruger’s favour, stating that he had been nice to them, had looked after them, had protected them and seen to their welfare as best he could during the war.

Eventually, Kruger was released from custody in 1948 and got a job at the Hahnemuhle Paper Mill…ironically, one of the places responsible for making the paper he used in his forging operations! He died in 1989 at the age of 84. The Hahnemuhle Paper Company is still operating today.

So much for Kruger. What about the banknotes?

Most of the leftover funds ended up here – Lake Toplitz in Austria, where crates of banknotes and equipment were dumped in the dying days of the Second World War. Expeditions and dives in subsequent decades hauled up some of the estimated 100,000 pounds sterling of forged banknotes which had been disposed of in the lake, and today, these forged banknotes are highly collectible as historical artifacts.

Want to Know More?

Most of the information for this posting came from the excellent documentary film “The Great Nazi Cash Swindle”, from 2004, which you can find on YouTube.

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/operation-bernhard

[…] Operacja Bernhard zakończyła się w 1945 roku, kiedy zbliżające się siły alianckie zmusiły Niemców do porzucenia projektu. Fałszywe banknoty, które nie zostały użyte, zostały spalone lub zatopione w jeziorze Toplitz w Austrii, gdzie część z nich została odkryta dopiero po wojnie( Throughout History). […]