The night air is crisp, the seas are rolling, the ship is rocking as it ploughs through the waves, swaying back and forth, the muffled sloshing of the distant water sending you to sleep. To the casual observer, nothing is wrong, and nothing would be wrong, if not for a series of individually inconsequential events, which all conspired to create one of the greatest maritime disasters which few people today have ever heard of.

Everybody has heard of the sinking of the Titanic. If you’ve studied First-World-War history, then you’ll also be familiar with the sinking of the Lusitania, and maybe the Wilhelm Gustloff, if you’ve studied Second-World-War history. But how many people have ever heard of the sinking of a ship called the S.S. Atlantic?

To most people, the S.S. Atlantic sounds like the title of some cheesy 1970s B-movie disaster-film. The name just sounds so generic and bland and made-up-on-the-spot because somebody in charge of the creative processes for the movie couldn’t come up with anything more original! And yet, despite the rather uninteresting-sounding name, the story of the steamship Atlantic is probably more dramatic than any disaster-epic that Hollywood could’ve dreamed up back in the age of bell-bottoms, disco balls and loud, garish suits.

In this posting, we’ll be exploring the true story of the wreck of the S.S. Atlantic – when it happened, how it happened, and why.

What was the S.S. Atlantic?

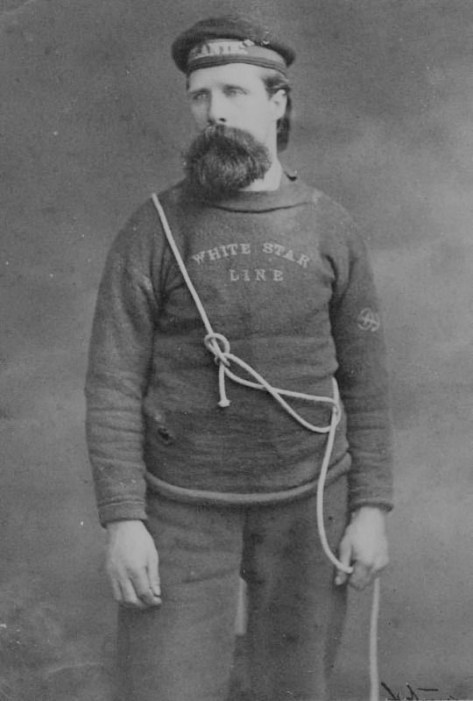

Launched in 1870, and departing on its maiden voyage on the 8th of June, 1871, the SS Atlantic was the latest in a series of ships built by Harland & Wolff – shipbuilders – for a company owned and operated by a man named Thomas Ismay – the company? The White Star Shipping Line.

The Atlantic was meant to be the second ship in the new ‘Oceanic‘-class of steam-powered sailing ocean liners. The others being the Oceanic, the Baltic, and the Republic. These ships were designed to be the most modern and up-to-date ships used by White Star since the company’s purchase by the Ismay family back in the 1850s. Previous ships were all sailing cutters, which differed little from other sailing ships of the early 1800s. By the second half of the 19th century, however, sufficient advances had been made in the area of maritime steam engines that the Atlantic and her sisters were among the first in this new generation of steam-powered sailing ocean liners.

And yes – I said steam-powered sailing ocean liners.

While White Star had started experiments with steam-powered ships as far back as the 1860s, the fact of the matter was that the public had little faith in these new ships – hard to blame them when a steam explosion on board the SS Great Eastern back in the 1850s, had killed 6 people!

To try and reassure the public that these ships were reliable (or at least, that they wouldn’t be in any danger if they weren’t!), early steam-powered ocean liners were still fitted with a complement of masts, rigging and sails – in this way, if the coal ran out, or if the engines broke down in the middle of the ocean, the ship could still be powered by sails. That said, sails were only ever seen as a secondary propulsion option. Since companies were eager to embrace the easier and faster method of steam propulsion, they would only have been hoisted in the event of a real emergency.

Along with steam engines, the S.S. Atlantic featured other new innovations. The creation of steamships had caused a big design-shift in how ships were laid out. In the past, ships were always steered from the back, with the helm (steering wheel) mounted on the poop-deck over the tiller and rudder. Because steamships had huge smokestacks in the way, positioning the steering wheel all the way at the back was just no longer practical – it just wasn’t possible to see where you were going, past all the smokestacks, and the smoke, and the rigging…you get the idea.

To stop mariners from sailing blind, the ships’ wheels were now positioned forward, in a new structure known as the wheelhouse, and the steering mechanism was connected to the rudder by a series of gears instead of ropes and pulleys as they had done in the past. In many cases, the wheelhouse was built into a larger structure around and behind it, encompassing officers’ quarters, navigational chart-rooms and meeting rooms known as the ship’s bridge.

The ‘bridge’ was a new design feature on steamships, and they dated all the way back to the earliest paddle-steamers (think about the riverboats that you see on the Mississippi). Initially, the ‘bridge’ was…quite literally…a bridge! A long, flat, railed structure that bridged the gap over the hull, from one side of the ship to the other. By standing on the bridge, the ship’s captain and his officers could see everything that was going on, without getting in the way of passengers on the main deck below. It also allowed them to move quickly from one side of the ship to the other to inspect paddle-wheels, or to watch out for dangers such as rocks, icebergs, and other ships.

Along with repositioning the steering wheel to make navigation easier, enclosing it and the officers’ quarters in a new bridge superstructure and wheelhouse, and replacing ropes and pulleys with more reliable geared steering mechanisms, the Atlantic and her sister-ships had another innovation: The engine-order telegraph!

Engine-order telegraphs were used to convey orders from the bridge down to the engine-room below, regarding the ship’s speed and direction. Orders were typically FULL AHEAD, HALF AHEAD, SLOW AHEAD, DEAD-SLOW AHEAD, STANDBY and STOP – with the same repeated for reverse (or ‘ASTERN’). Pulling the handles on the telegraph would strike a bell which could be heard down in the engine-room, alerting the engineers to the requested change in speed or direction. The engineers (who had identical telegraphs down below) responded to the orders from the bridge by pulling their own telegraph levers to the appropriate position, indicating that the orders had been received, and were being acted upon. This was indicated up on the bridge by the ringing of another bell, so that the officers on watch knew that the engine-order changes were imminent.

The Atlantic was large for the day – it could transport over 1,000 passengers, after all, spread across four decks. The ship boasted ten lifeboats, a steam power-plant capable of 600hp, and a top speed of just over 14kt (approx 27mph), which was just fast enough to ensure a weekly service between Europe and America.

Sailing on the S.S. Atlantic

The S.S. Atlantic had a very successful sailing career…right up until it didn’t…and crossed its namesake ocean, running the transatlantic route between Liverpool and New York several times without incident. The second half of the 1800s saw a huge rise in the number of passengers sailing between North America and Europe – principally Canada and the United States on one side, and Britain, France and Germany on the other. The rise of steamships in general meant that for the first time, it was possible to actually have a reliable service of ships between North America and Europe.

A steamship, traveling at a set rate of speed, could do the one thing that sailing ships never could: Arrive on time! Not being reliant on weather and wind-power, steamships and the companies that operated them, could do the one thing that sailing ship companies never could: Have an actual sailing schedule! For the first time in history, you could say with fair reliability, that you would leave Southampton, or Liverpool, or Cherbourg, on Friday, and arrive in New York or Boston, or Montreal, the following Friday – and that exactly one week after arriving, you could sail home again if you wished, because exactly a week after you arrived, another ship would have arrived from Europe to take you home again!

Because of this, companies like White Star were desperate to have new fleets of ships that could capitalise on this suddenly gigantic market of people who wanted to travel – immigrants looking for a new life, titans of industry traveling for business, families going across the ocean to visit relatives or friends, and people journeying to Europe to take the Grand Tour! The steamship and its older brother, the steam-train, had given birth to an age of mass travel and tourism!

Having a reliable service did come with other advantages: for the first time, fresh food was available to paying passengers! Since nobody ever expected to spend more than a week or two at sea, it was finally possible to load fresh provisions on board, knowing that the voyage would be over (or nearly over) by the time they went off.

While speed, reliability and catering had definitely improved – not everything had. For example – sleeping arrangements. Ships like the Atlantic had a two-class system: steerage-class for paying immigrants and people looking to cross the Atlantic ocean on the cheap, and more affluent ‘Saloon-Class’ passengers…the closest equivalent to First-Class in the 1870s.

Like as on other ships of the era, passengers were segregated, typically into three (or depending on how you count them, four) broad groups: Single men, married couples and/or families with children, and finally, single women. Your marital status determined where you were allowed to sleep on the ship. Single men were housed forward of the main saloons and lounges, in the front of the ship. Couples, or families with children, were housed in the middle of the ship, and single women were housed at the back, or stern.

The idea behind this arrangement of the cabins (which ranged from comfortable four-berth family cabins, to two-bunk arrangements for couples, etc) was that respectable, upstanding men and women of good breeding, married (or nearly married) and with children, would be a suitable and safe barrier to prevent horny, single young men from falling upon defenseless, single women!

By separating single men and single women with married couples and families in the middle of the ship across both saloon or cabin-class passengers, and steerage-class passengers, the ship would avoid any instances of unwanted groping, sexual assault or other instances of shocking impropriety! The segregation between the various groups aboard ship was firmly enforced by the ship’s officers and stewards.

The two classes on board the Atlantic were divided, not only by marital status, but also by class, and class determined where you could go on the ship. For example, saloon or cabin-class passengers had access to the lounge and dining saloon, but also access to the open main decks, so that they could see the views of the sea around them as the ship steamed along. The ship’s dining room or saloon was the largest, most open room on the ship, and even included a piano for passenger entertainment. Steerage passengers could only move around within the interior of the ship, and not out on deck. While they were free to mix and mingle among themselves during the day – after lights’ out at 11:00pm each night – everybody was expected to know their place – to be in it – and not to leave it until the next morning!

As far as steamers went, the Atlantic was modern in many respects, boasting flushing toilets, hot, running water (warmed by the steam that drove the engines), fresh hot food, and technological advancements which would ensure a faster, and safer crossing. The ship also boasted one of the first uses of electricity at sea – not in electric lighting – not even in wireless telegraphy – but in call-bells. Passengers lucky enough to book cabin-class tickets had the benefit of call-buttons in their cabins, as well as in other parts of the ship such as the main public rooms. Stewards could now literally be summoned at the press of a button!

That said, the ship was still old-fashioned in other respects: For example, in an age before the widespread use of electricity, lighting the ship was done entirely by oil-fired lamps and candles – a significant safety-hazard on a rocking, rolling steamship in the middle of the ocean. In fact, one of the duties of the ship’s stewards on the Atlantic was to be on the lookout for smashed oil-lamps in heavy weather, when they might fall, break, and spread flammable liquid all over the floor.

The Last Voyage of the Atlantic

The Atlantic was considered a highly successful, and safe, ocean liner. Food was plentiful, cabins were comfortable, and the amenities were surprisingly modern. Remember that most homes in the 1870s didn’t have hot, running water, flushing toilets and central heating! Since its maiden voyage in 1871, the Atlantic had had nearly twenty successful voyages between New York and Liverpool and apart from a minor tussle involving bumping into another ocean-liner (a common accident in those days), it had a spotless record of sailings.

Everything changed on the 20th of March, 1873.

On that day, the Atlantic departed Liverpool as usual, and nothing was seen to be out of the ordinary – just another Thursday, like any other. On board were 835 passengers, including 14 stowaways, and two pregnant women (who gave birth during the voyage). The ship followed its usual route sailing past the southern Irish coast, and then out into the transatlantic shipping lanes.

The journey was hard going. The weather was hardly ideal, and the heavy, rolling seas meant that the ship was fighting against the swells for every yard of forward momentum. In command is Captain James Agnew Williams. Beneath him are the Chief Officer, John Firth, 2nd Officer, Henry Metcalf, 3rd Officer, Cornelius Brady, and 4th Officer John Brown. Unlike on later, and larger ships, the position of Chief Officer and First Officer (which, for example, on the Olympic-class ships of the 1910s, were separate positions), were combined into one position in the 1870s.

Along with the deck-officers are a number of other crew, including up to seven engineering crew, six quartermasters, the ship’s surgeon or medical officer, and several dozen members of the crew, mostly able seamen. In total, officers and crew numbered 143 in total.

The 830-odd passengers included 32 passengers in “saloon” or “cabin”-class, and 615 passengers (men, women and children) in steerage. In all, there were 86 children aboard, approximately 40 each, of boys and girls, of various ages, ranging from toddlers and infants, to adolescents.

Thus loaded, the Atlantic set out to cross the ocean which it had done so many times in the past with no issues. As the ship sailed further westwards, however, the weather, fresh to begin with, only started getting more and more turbulent with every passing day. During his daily rounds, Captain Williams would confer with his officers regarding speed, position and heading. He would also speak to Chief Engineer John Foxley for a report on the engines, boilers, and most importantly – fuel consumption. Like every steamship of the era, the Atlantic was a coal-fired steamer, with coal being brought from the coal-bunkers on wheelbarrows, by trimmers, to be dumped next to the boilers, whereupon it was shoveled into the furnaces by stokers or firemen.

It was the job of Foxley and his fellow engineers to keep an eye on things like steam pressure, lubrication, and wear and tear on the engines – especially important during rough weather. It was also Foxley’s job to inform the captain of any issues involving the engines, boilers, or fuel-supply. One of Foxley’s daily tasks was measuring fuel consumption. Every day at the same time, he would have to determine how much coal had been burnt in the last 24 hours, against how much coal they had left, and how far they could travel on the reserve.

The voyage was rough. While the Atlantic’s billed top speed was 14kt (maybe 15 in good weather), during the heavy seas on its latest crossing, the ship would be lucky to reach 12kt, with the whole vessel pitching and rolling with every wave.

Halfway through the voyage, during one of his daily inspections, Captain Williams asked Foxley for his usual morning coal-report. Foxley duly gave his morning report about the amount of coal still available onboard for the onward journey. However, the information provided to the captain was not always 100% accurate. Engineers routinely under-represented the amount of coal left in a ship’s bunkers during the voyage. This practice meant that the amount of coal reported was always less than the actual amount of coal available. The reason for this was very simple – in the event of a real emergency, there would actually be more coal than reported, to keep the ship going.

Into the Storms

As the Atlantic’s voyage continued, Captain Williams grew increasingly concerned. A trip that usually took a week was now taking eight days…nine days…ten days. The storms that the Atlantic had started to encounter were not dissipating, and the ship’s engines continued to struggle against the heaving waves. Just seven days out from England, the ship was hit broadside by a rogue wave that reached as high as the boat-deck, tearing lifeboat #4 from its davits and washing it out to sea.

It was through these fearsome waves that the ship had to fight, constantly slowing its engines to prevent mechanical failure. From 14kt down to 12, down to 8…down to 6kt…the Atlantic was struggling to make headway, and while the ship was in no danger of sinking – there was another danger: Running out of coal.

Just to maintain speed and heading, the ship’s engines were burning enormous amounts of coal to keep up the seam pressure required to power the engines, and the ship was still nowhere near New York City. Fearing that the ship might run out of coal before it reached New York, Captain Williams decided to take emergency actions, and executed the 19th century equivalent of an emergency aircraft landing – premature docking.

In the event of a ship running low on coal, it was common practice to divert to the nearest port, drop anchor, re-coal the ship and then continue on to your original destination, however, re-coaling mid-voyage was usually seen as an action of last resort. Coaling halfway to your destination suggested that the ship had not been properly provisioned when it left its home port, or else, had been poorly managed during the voyage – either instance being an embarrassing miscalculation which would reflect badly on the ship’s crew, and by extension, the shipping line that employed them! After all – the whole purpose of taking a steamer was because they were more reliable – what was the point of taking a steamer if the steamer had to keep stopping for coal?

Diverting to Halifax

Despite efforts to conserve coal, the Atlantic still appeared to be running out of fuel. Two days out from New York City (approx 400 miles), Captain Williams once again asked Foxley about the coal situation. Foxley knew that the ship still had 160 tons aboard, but – as was his habit in under-representing the amount of coal on board, so that there would be a fuel-reserve for emergencies – Foxley reports 127 tons remaining.

Williams knew that the ship required at least 130 tons to reach New York – less than what the ship actually had on board – but thanks to Foxley’s misrepresentations, Williams decides to err on the side of caution instead. Not wanting his ship to be caught literally dead in the water with no steam, he decides to divert to the nearest major port to re-coal his ship, re-provision with fresh food, drinks and other necessities, and then proceed to New York fully stocked (or at least, stocked enough to reach New York with supplies to spare).

The ship’s officers prepare to alter course, from West-Southwest, to Nor-Northeast, heading, not for New York City – but for Halifax, Nova Scotia. While ships docking at Halifax is a common occurrence, for the purposes of coaling and re-provisioning, the Atlantic has one great disadvantage:

None of the officers have ever gone to Halifax before. Never having traveled there, they were not familiar with the harbour conditions, nor the precise layout of the coastline, and to make things even more treacherous, they will be traveling there at night, in stormy conditions, which would make the ship harder to control.

With coal-supply no longer an issue, Captain Williams orders to officers on watch to alert the engine-room to the change in direction and destination. The telegraph on the bridge is set to Full Ahead, so that the ship may arrive as soon as possible, thereby reducing as much as possible, any chances of delays once they have arrived in Canada.

Halifax Harbour, while one of the largest harbours on the Canadian Atlantic coastline, is filled with dangers. While the harbour is wide, it is also shallow, and running aground on sandbars and rocks is a real risk. To guide ships towards the harbour, in 1759, the Sambro Island Lighthouse was erected on Sambro Island near the harbour entrance. Captain Williams knows this, and gives orders to Second Officer Henry Metcalf, officer-of-the-watch, to keep an eye out for the lighthouse. The captain’s orders are clear:

The ship is to proceed at its current speed and heading until it either spots the lighthouse, or until 3:00am – whichever comes first, upon which time the captain was to be roused from his sleep, the anchors dropped, and the ship would stop engines and wait out the storm, in preparation for entering Halifax at dawn. It is now the 31st of March.

The Approach to Halifax

As the Atlantic changes course towards Canada, Captain Williams declares that he is going to bed. He leaves his instructions with Officer Metcalf, as well as a separate order with his personal steward, to wake him just before 3:00am, the time specified that the ship should stop for the night. The captain retires to his cabin, but before he can turn in, a newspaper journalist traveling as a passenger asks for a brief interview. The captain agrees, and the two men retire to his cabin to talk. Past midnight, the journalist finishes his interview and leaves the bridge. Captain Williams turns in.

On the bridge are Officer Metcalf, and quartermaster Robert Thomas – as on most ships of the era, the actual steering of the vessel is managed by quartermasters, usually nicknamed ‘QM’s’ for short. At the very front of the ship, able seaman Joseph Carroll is acting as forward lookout. To starboard is Patrick Kiely, and Fourth Officer Brown is patrolling the ship’s stern, along with quartermaster Charles Roylance, who is also the aft lookout.

By now, it is 2:45am, April 1st. As requested, the captain’s steward walks onto the bridge and heads to the captain’s cabin to wake him up. However, he’s intercepted by Officer Metcalf, who says that the captain is not to be disturbed. Ahead, the sea is stormy, but there are no obvious obstructions in sight, giving Metcalf the incorrect assumption that the ship is on course for Halifax. What neither he, nor any of the other crew realise is that the Atlantic is not actually heading towards Halifax! The storm has blown the ship far off course, twelve miles west of the harbour entrance.

Unaware of this, the ship’s officers and lookouts expect to spot the beacon of Sambro Island Lighthouse any minute now, off to the port, or left, side of the ship’s bow. Quartermaster Thomas, one of the few crew on board who has actually traveled to Halifax before, grows suspicious – surely if they were on course, they would’ve seen the lighthouse by now? He informs Officer Metcalf that the ship may be off course, and that they should either slow down, stop, or alter course as a precaution.

Before Metcalf can decide what to do, the two forward lookouts called “Breakers ahead!“. Officer Metcalf realises too late that the ship is heading, not for the open mouth of the harbour, but towards the Nova Scotia coastline! As with the Titanic, the next order is “Hard a’Starboard!“, the order to turn the ship’s wheel hard to the right, to push the tiller in that direction, thereby steering the ship left! Metcalf’s next order was for the ship’s telegraph – FULL ASTERN. Before the ship can clear the rocks and make a full turn, however, it slams headfirst into the breakers off of Meagher’s Island!

The grinding, screeching sound wakes up the passengers and the ship’s keel is torn out like a tin can! The shuddering and vibrating makes some passengers think that the ship has finally arrived in Halifax, and that the anchor-chains are being dropped to keep the ship from drifting.

The sudden loss of momentum causes the ship’s slipstream to rush through the vessel, extinguishing almost all the lamps and candles in the corridors and cabins, plunging the ship into almost total darkness! Captain Williams is thrown awake from the impact against the rocks and rushes out onto the bridge. The time on the wheelhouse clock: 3:15am.

Captain Williams took immediate charge of the situation. He orders the ship’s engines to remain at FULL ASTERN, so that they can reverse the ship off the rocks, but before the engines can affect any kind of serious movement, another huge wave hits the stern of the ship, throwing it up onto the rocks! The Atlantic is now broadside to the shore, with its port (left) side facing the sea, and starboard side towards the shore.

Officer Metcalf orders the lifeboats to be swung out, and loaded with women, children and what few men there are around. The captain decides that this is suicidal – with the waves so high, there is no way to row the ship’s ten lifeboats to shore, and orders the passengers out. Metcalf refuses to leave, and the lifeboat with the men onboard, and himself as commanding officer, is lowered down the port side into the sea.

Once the lifeboat was cut free from the falls connecting it to the ship, the massive waves which had so successfully shifted the entire ship up onto the rocks grabbed the lifeboat and smashed it against the hull, obliterating it completely, and killing everybody aboard – including officer Henry Metcalf.

With the ship not appearing to be in any immediate danger, the captain ordered everybody on deck. Stewards walked through the corridors, knocking on cabins to wake up passengers and order them up onto the boat-deck. On the bridge, Captain Williams issues another order, to the two quartermasters on duty: QM Roylance, and QM Speakman. They are to begin the process of calling for help.

Wrecking on Meagher’s Island

With the ship stuck fast on the rocks, Captain Williams has to decide what to do next. Not being awake at the time of impact, Williams has no idea where the ship is, and with the lamps extinguished because of the crash, there’s almost no light with which to see for him to try and pinpoint their position.

After raising the alarm and canceling any further attempts to evacuate passengers by lifeboats, the captain orders the two quartermasters, Roylance and Speakman – to begin summoning help.

30 years before the advent of wireless telegraphy, the two quartermasters are limited in using whatever they can find to raise the alarm. They open a crate of flares and, standing on the bridge, they start launching distress rockets high over the ship, and into the storm. They use the only source of light – the still-burning binnacle lamp on the bridge – to ignite the rocket-fuses and launch them into the sky. It’s hoped that the sound of the rockets exploding, or the flash of the flares, will alert villagers on the island to the presence of the sinking ship.

Wedged across the rocks, the Atlantic starts to take on water, and becomes unstable. Pounded by waves, every last one of the ship’s ten lifeboats are either smashed against the hull of the vessel as they’re lowered into the sea, or else are torn off the davits before they can be loaded.

As Roylance and Speakman continue to light and fire the distress rockets, the stern of the Atlantic shifts dramatically and the propeller strikes the rocks under the keel, shearing off the blades and causing the propeller-shaft to over-spin. Chief Engineer Foxley orders the engines to be shut down, and prepares his fellow engineers to evacuate the ship’s engine room and boiler rooms. Before leaving, they open the safety valves on the boilers, discharging the pressurised steam inside, to prevent a catastrophic boiler explosion. Further destabilised by the loss of the rudder and propeller, the ship rocks violently and the aft end slides off the rocks which it had been swept onto, and starts to sink.

As the stern slides off the rocks and into the water, calamity is unfolding below decks. Unable to find their way out of the rapidly flooding passenger quarters in the pitch-blackness, hundreds of women and children drown in their cabins, or in the corridors that lead to the boat-deck. The bow, still out of the water and wedged on the rocks, fares slightly better, and male passengers and some crew, housed in the bow and admiships, are able to scramble out on the hull by opening portholes or smashing windows.

Escaping the Sinking Ship

What passengers and crew which had managed to scramble out of the ship started climbing onto the railings, rigging and masts of the ship to keep them from being swept off the decks and into the waves. As the ship rocks even further, Speakman and Roylance are unable to keep firing rockets. Up to now, eight have been successfully discharged from the bridge. As they prepare to fire the ninth, the ship rocks and the rocket explodes prematurely, hitting both men in the face. Before they can recover, or fire off more rockets, the rolling hull of the ship causes the crate containing the rockets to be thrown off the bridge and into the sea.

By now, the stern is almost entirely underwater and the ship is listing 30 degrees to port. To keep the passengers and crew safe, the officers, led by Chief Officer John Firth, direct the passengers to climb onto the ship’s masts and yardarms. At least here they will be able to hold on, or sit in the rigging, high enough out of the water that they won’t be hit by the waves, while they figure out how to evacuate them.

What nobody has yet realised is that one member of the crew has already made it to land – Quartermaster Robert Thomas – the helmsman – was thrown off the ship and washed ashore. Alive, he scrambles to his feet and runs up the cliffs to try and find help. At the same time, at a farmhouse on Meagher’s Island, the O’Reilly family is roused by the sounds of – what they initially believed – to be artillery-fire! The head of the family runs out into the storm and witnesses the last of the Atlantic’s distress rockets being fired into the air. As he runs in the direction of the flare, he stumbles into somebody coming the other way – Quartermaster Thomas!

Mr. O’Reilly takes Thomas back to the farmhouse and warms him up while his family provides him with food and drink. Thomas relays the news of the wrecking of the steamship Atlantic and together, the two men rouse the inhabitants of the island to mount a rescue mission. For the first time since 3:15 that morning, the crew of the Atlantic have finally discovered where they are – on the south side of Meagher’s Island.

While Thomas is raising the alarm on Meagher’s Island with the help of the O’Reilly family, Quartermaster Speakman has started trying to rescue passengers and crew from the sinking ship. With a rope, he has managed to swim to the nearby Golden Rule Rock, and after establishing a lifeline, starts guiding people ashore.

It’s at this time that Mr. O’Reilly and Quartermaster Thomas arrive back at the wreck-site. Speakman returns with Thomas and Mr. O’Reilly to the farmhouse, where Mr. O’Reilly’s daughter, Sarah, has started preparing bread and soup for any survivors, which are now slowly making their way inland and towards the O’Reilly farm.

Building on Quartermaster Speakman’s efforts, the other members of the Atlantic’s crew start stringing out more lifelines. Ropes taken from the ship are lashed to the railings around the bow and are then swum across towards Golden Rule Rock. In time, five such lifelines have been established, and one by one, survivors start swimming from the ship to the shore, holding onto the ropes for support as they go, some of them bring more ropes so that a further lifeline can be linked between the rock itself, and the beach nearby.

On the ship itself, passengers try to rescue the men still trapped inside the ship. Using whatever tools they can find, those outside the ship walk along the sloping hull of the bow to where those inside hammer against windows and portholes to get their attention. Portholes are either opened or smashed with tools, and roughly 100 men are rescued from inside the ship.

One passenger who is able to fight his way out of the hull and onto the sloping hull with the help of the other survivors, is John Hindley, a 12-year-old boy. As the stern sinks into the crashing waves, every single woman and child aboard the Atlantic is drowned instantly. Hindley survived only because he had begged his mother and father to be allowed to sleep in the men’s quarters with his older brother, at the bow of the ship. This change in sleeping arrangements saved his life, and he was able to escape the sinking ship onto the decks while the childrens’ quarters at the stern sank into the waves.

By now, the residents of Meagher’s Island, and nearby communities, have heard about what has happened, and begin mounting rescues of their own, taking to the rolling seas in fishing boats, and multi-oared, shore-based lifeboats. Survivors are collected from Golden Rule Rock and rowed to Meagher’s Island, while other lifeboats row to the wreck to help survivors on the ship to escape. One of the last men off the ship is Captain James A. Williams, who later recounted his experiences, and how fearful he was that the ship would break its back at any moment, split in two, and sink.

Rescuing the Last Survivors

As dawn broke, the majority of the ship’s surviving passengers and crew had been rescued, either from Golden Rule Rock, or from the wreck of the Atlantic itself, but as the sun rose, it was suddenly realised that the ship still had survivors on board!

Chief Officer John Firth, passenger Rosa Bateman, and an unnamed cabin-boy had spent the whole night sitting in the mizzen mast of the wrecked ocean liner. Too high up for rescuers to reach, and too exhausted to climb down or jump and swim to a lifeboat, they had been abandoned, with the villagers on Meagher’s Island unable to find a safe way to rescue them.

Their salvation – for some of them, at least – came from an unlikely source – Reverend William Ancient – a clergyman on Meagher’s Island.

Ancient, a former sailor of many years’ experience, had retired from the navy to become a priest, and upon waking on the morning of the 1st of April, hurried to the wreck-site when he heard what had happened. With another lifeboat and a crew of villagers, he rowed out to the wreck and started to try and find a way to reach the three survivors trapped in the rigging. The cabin-boy jumped and was picked from the water. Officer Firth had a rope tied around him and then he too, jumped, and was hauled from the sea. Rosa Bateman, the only female passenger to escape the ship, was not so fortunate, however.

Tied to the mast by Officer Firth in an attempt to stop her from being swept out to sea, Mrs. Bateman had died of hypothermia by the time Reverend Ancient and his fellow rescuers had reached her.

Of the roughly 950 passengers and crew on board, only about 400 had survived – all of them men. Not a single woman, and only one child – 12-year-old John Hindley – had survived the the wreck of the S.S. Atlantic.

The Aftermath of the Disaster

In the days and weeks that followed the disaster, the villagers of Meagher’s Island and the survivors of the shipwreck all struggled to piece together what had happened, what had not happened, and what would happen next.

The most immediate issue was what to do with the ship.

By the afternoon of the 1st of April, 1873, the Atlantic had slipped entirely off the rocks upon which it had run aground, broken in half, and was starting to sink. Divers approached the wreck to retrieve the bodies of dead passengers and crew, some even using dynamite to blast the wreck apart to retrieve, not only the corpses, but also personal belongings of the survivors, and the cargo in the ship’s holds. The dead were laid out on the beach where the ship’s surviving officers stood guard over them, until such time as they could be prepared for burial.

Once the ship’s dead and its cargo and other items had been retrieved, the vessel was plundered and looted by villagers looking for anything leftover which might be of value. The cargo, waterlogged and damaged, was the subject of insurance-claims, which were duly paid out. Un-sellable, the ruined cargo was auctioned off to the highest bidders, to do with, or use, as they saw fit.

The bodies were buried across at least three cemeteries, including two for the protestant, and catholic victims of the disaster. Reverend Ancient, who had rescued Officer Firth and the cabin-boy, presided over the protestant burial service.

Funds raised by the White Star Line, the city of Halifax, Nova Scotia, and other entities paid for such things as prizes and rewards for the heroes of the disaster, and compensation for the losses. Reverend Ancient received a gold hunter-pocketwatch in recognition of his efforts in saving Officer Firth and the cabin-boy, the last two people rescued from the ship before it sank entirely.

So, what happened afterwards?

Like with the sinking of the RMS Titanic, 40 years later, the Atlantic was subjected to a full court of inquiry to determine what had happened. In the end, the court found Captain Williams guilty of mismanagement of the ship and poor command of his crew. The White Star Line was blamed for insufficient coaling of its vessels (although this was later disproven and the charges dropped). While he shouldered most of the blame for what had happened due to his previous actions such as not staying on duty through the night, and not being fully aware of the ship’s fuel-situation, Captain Williams was nonetheless praised by the court for his leadership and direction during the disaster itself.

The Atlantic Today

The wrecking of the S.S. Atlantic faded from public consciousness with surprising swiftness. Two private cemeteries, and a memorial cenotaph, are the only period-reminders that the Atlantic was ever lost at all, and even these were quickly forgotten. The cenotaph was only rediscovered and restored in the 1980s!

Perhaps the most telling example of how quickly people forgot about the wreck of the Atlantic happened in 1929. It was in that year that a film was released, titled “ATLANTIC”! It’s a thrilling tale of death, disaster and mayhem at sea! Of a ship with not enough lifeboats! A ship that strikes an iceberg and which sinks with over a thousand people still trapped aboard! A ship named!…the RMS Titanic.

Yes that’s right. 1929 saw the first-ever “Titanic” ‘talkie’ film, with full music, sound-effects and dialogue. Because the White Star Line was still in operation when the film was being made, the producers could not use the name ‘Titanic’ in the title. To get around this, the filmmakers simply renamed their film to what they thought was a more generic title!…Unwittingly naming one disaster film after yet another disaster from the history of the White Star Line! So obscure had the wreck of the Atlantic become, just 56 years after it had happened, that nobody had realised the coincidence!

Today, the memory of the S.S. Atlantic is kept alive in Nova Scotia through museum exhibits, interpretation centers and historic parks, either in Halifax, or nearby Meagher’s Island (today renamed Mars’ Island), where artifacts, models and personal mementos from the wreck are on permanent display, telling the story of the White Star Line’s greatest shipwreck before the disaster of the Titanic, which so overshadowed it that the wrecking of the Atlantic became lost to history…

Further Reading

Want to find out more about the wreck of the S.S. Atlantic? Here’s the sources used for this posting, which cover the sinking in greater detail…

http://www.norwayheritage.com/articles/templates/great-disasters.asp?articleid=1&zoneid=1

The Passengers & Crew of the S.S. Atlantic – this is an amazing resource. It attempts to list every single person on board the ship during its last voyage (keep in mind that the information here is taken from period records, so is not 100% accurate).

https://vocal.media/wander/s-s-atlantic

The S.S. Atlantic Interpretation Center

Documentary film on the sinking of the S.S. Atlantic

[…] https://www.throughouthistory.com/?p=4712 […]

Very interesting.

I was just in Nova Scotia last October, 2024.

I did go to the museum.

I wish that I had read more about this Ship.

The friend that I was with bought your book.

I’m very interested to read more about this Ship.

Thank you.

Janie Niswonger

4685 SE 37th Ct.

Ocala, Florida 34480-7354