Steam wafts out and smoke blasts from the smokestack. A bell swings back and forth, dinging and clanging and a powerful steam-whistle lets out a deafening, farewell blast! Metal creaks and rattles and an enormous and majestic locomotive powers its way out of the station and off into history. On the platform, wellwishers, friends and relatives wave goodbye to the passengers lucky enough to ride on one of mankind’s most amazing inventions ever…the original ‘choo-choo’ train…the steam-powered locomotive.

For over 100 years, steam-trains have been objects of mystery, romance, amazement and awe. From the first quarter of the 1800s until the 1950s, these giant, fire-eating, smoke-belching, steam-pumping monsters have transported billions of people billions of miles across the countries of the world. Even though they’ve long since been made obsolete by the rise of diesel and electrical-powered trains, steam locomotives continue to capture the imaginations of millions of history-buffs, train enthusiasts and mechanical maniacs around the world. This article will look into the history, evolution and workings of the boyhood dream of thousands of fully-grown men: the operation and the working lives of the railroads and the original, classic…choo-choo train.

Before the Steam Locomotive

It’s hard to imagine the world without trains these days, isn’t it? Imagine going from Sydney to Melbourne, from London to Edinbrugh, from Chicago to Los Angeles…by car! A trip that would take a few hours or a couple of days by train, would take days or even weeks by car. But before even cars came along, you would have to make those same arduous, dangerous journeys with a horse and cart, which would take even longer. In the western United States, going from San Francisco to Chicago meant a long, dangerous and sometimes even deadly journey by covered wagons rumbling in convoy-formation over dusty, bumpy roads through the middle of nowhere. You were susceptable to breakdowns, starvation and Indian attacks. In both the US and the UK, travelling long distances was a matter of loading up a stage-coach and rumbling off down the road. Stage-coaches were so-called, because they completed their journeys in stages. You rode from point A to point B, but on the way, you had to stop at Stage 1, Stage 2 and Stage 3 on the road, to change or rest the horses, to buy food or to repair damage to your coach or carriage. It was dangerous and long going…and you can bet it wasn’t very comfortable.

The Birth of Steam

Before steam locomotives came along, there were just steam ‘engines’. A steam ‘engine’ is simply a device, powered by steam, that performs a task, and which doesn’t necessarily move a train across a set of tracks.

The idea that the vapour from boiled water, pressurised and released at regulated intervals, could move machined parts to create a working contraption practical enough to have an application in the manufacturing or production industries, is an old one. People had been toying with steam-power for centuries. The first steam-powered machines were stationary ones: These steam-engines powered pumps which pumped water. Other steam-engines might provide power to looms or mills to make textiles or to crush grains to make flour. But sooner or later, someone was bound to ask: “Why can’t these engines move themselves instead of moving something else? Why can’t they move…people instead?”

The idea of using steam-power as a form of transport, which naturally led to the creation of the steam locomotive, was born.

Experimental Steam-Trains

If you want to be really finicky about terminology, a ‘train’ is a line of cars or carriages or trucks, shackled together. Like a wagon-train, or a semi-trailer train. The machine that pulls the train and which provides the power, is the locomotive. These days, a ‘train’ and a ‘locomotive’ are generally seen as synonymous, and for the sakes of convenience and understanding, they’ll be just that, for this article.

The first steam-trains arrived on the rails in the very early 1800s. An Englishman named Richard Trevithick was able to construct a steam-engine small enough to be seated on a wheeled platform. Using additional wheels and pistons, he was able to show that steam-power could move a wheeled vehicle and that this technology might one day be used to transport people. Previous to this, steam-engines were huge, stationery objects, much too large to power a moving vehicle. The metallurgy to create strong and compact-enough steam-engines simply didn’t exist back then. But Trevithick was certain that he had something going here. And over the next few decades, other inventors and innovators would examine his designs and add or improve on them, to develop the steam-train we know and love today.

The first steam locomotives were treated much like the first cars were, about a hundred years later. They were seen as novelties. Silly little machines for the wealthy, which would never gain a prominent place in society. Early steam-trains were little more than amusement-park rides, such as the ‘Catch Me If You Can’ miniature-railroad which existed as a fairground attraction in England in the early 1800s. This train ran around an enclosed, circular track, and Britons could marvel at this whimsical little machine which they never imagined, might one day transport them hundreds of miles in a day!

The first practical developments in steam-locomotive technology started in the 1820s and 1830s. Men such as Robert Stevenson, began to see potential in steam-power. The potential to transport people and goods long distances. But in order to transport things, steam first had to be harnessed in a way so as to move a vehicle reliably. A big problem with early steam-locomotives was that the steam-pressure was unreliable and the power-output was so variable that nobody thought it would ever work. Pioneers like Stevenson changed this by inventing steam-locomotives such as the Rocket:

Stevenson’s ‘Rocket’ locomotive

While today this kooky little tin can on wheels hardly travels at ‘rocket’ speed (its max was a mere 29 miles an hour!), Stevenson’s design and his improvements on Trevithick’s early, experimental steam-trains, showed the public what a steam-locomotive could really do, if people were willing to have a bit of belief and were willing to do a bit of experiementation and development. The era of the steam-powered locomotive had arrived.

The First Practical Steam-Locomotives

Daring designers and inventors such as Stevenson had proved to the world that steam-trains were a practical means of transport. When people began to see how useful trains would be in transporting them greater distances, they began to get really interested in this new technology, and by the late 1820s, regular steam-train lines were operating in England, followed closely by the United States.

The USA was the natural place for steam trains to develop and grow into powerful machines. This wide, flat country needed a quick, dependable and safe way of crossing its vast stretches of land which would take a wagon train weeks to cross, when a steam-locomotive could take just days.

The first steam-trains in the US arrived in the early 1830s. They were imports from England, since America did not have the facilities to produce its own trains at the time. The trains which the English gave to the Americans were called ‘John Bulls’, presumably named after John Bull, what was seen as the national personification of the United Kingdom (much like how Uncle Sam is the personification of the USA).

A painting of a typical ‘John Bull’ locomotive, the kind of steam-train that existed in the USA in the 1830s

By the 1840s, the permanence of steam-locomotives had been established. Although still clunky, noisy and of questionable practicality and even though they transported people in uncomfortable, wooden carriages which were generally open to the elements, even though they rattled and shook like castanets, they were here to stay. Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, railroad lines spread across the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom, taking telegraph poles with them and linking up the states and counties of the countries which they were built in.

The Rise of the Railroads

Developments throughout the 19th century continued to improve and refine steam-trains until they more or less fitted into the idealised image that we have of them today. While everyone thinks that steam-trains burnt coal, the truth is that most early steam-trains actually burnt wood! Coal had to be mined and broken up. Wood just had to be chopped down and split into logs…something that people were doing all the time, anyway, so it was easier to get.

Locomotives started pulling longer and longer trains and passengers were beginning to enjoy the comforts and joys of train-travel. Journeys that took days by wagon now took a few hours by rail. You could leave one city in the morning, and arrive in your destination city by the evening. New communities and towns sprang up alongside railroads and people began to move around. Goods which previously were unavailable in one part of a country could now be transported cheaply and efficiently by trains, and commerce began to grow.

The American Civil War in the 1860s showed just how important trains had become. Steam-power allowed troops, ammunition, food and materials to be transported quickly to the battlefronts, and trains needed to become faster and more powerful.

The Transcontinental Railroad

Up until 1863, it had been a dream of American president Abraham Lincoln, to have a railroad that would lead from one end of the USA to the other. A big, strong, thread of steel that would sew the country up and bring it closer together. In 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, this dream was finally realised.

In a joint venture, two companies, starting at opposite ends, would build a single railroad line which would link Chicago and San Francisco. The Central Pacific Railroad and the Union Pacific Railroad were those two companies, one starting in San Francisco, the other in Chicago, working east and westwards, respectively.

Building the transcontinental railroad, or the ‘Overland Route’ as it was also called, was a major engineering feat. To the Chicago-based Union Pacific Co., the going was pretty easy, most of the land they covered was flat and easy to work on. But the Central Pacific Co. had to hack its way through the millions of tons of rock that made up the famous Rocky Mountains. To do this, they employed thousands of Chinese labourers. The Chinese had come to California about a decade before, looking for gold, but now, they were going to be used to aid in the cause of mechanical progress.

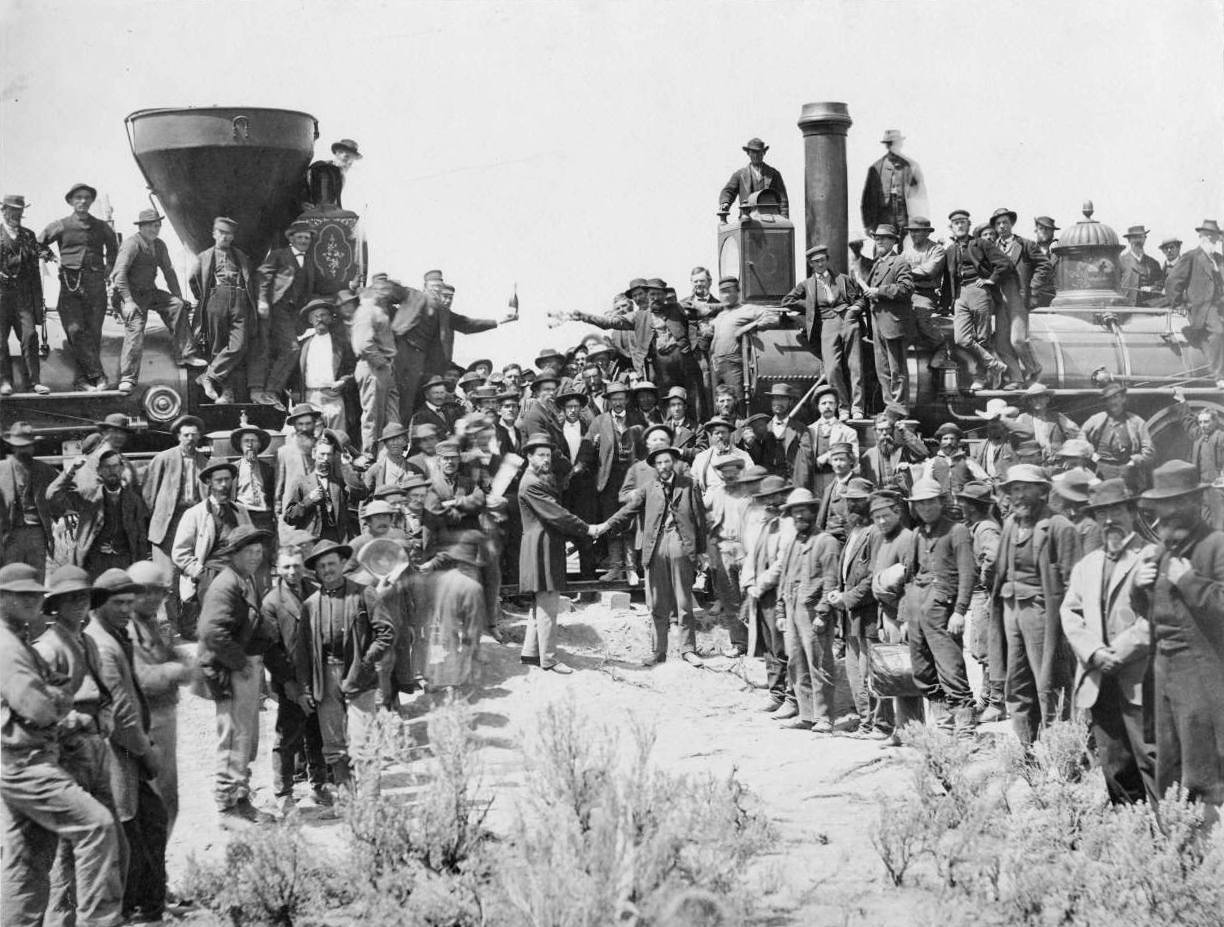

The railroad was finished in 1869 at Promontory Summit, Utah, where the Chinese and American workers of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads, in a ceremonial show of unified work, laid the last set of tracks together, and where the ceremonial golden rail-spikes were nailed into the ground, to signify the successful completion of Lincoln’s dream.

A photograph taken at the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad

The Golden Age of Railroading

With entire countries and continents now linked up by threads of steel, the Golden Age of the Railroad had begun, and it was being powered by nothing more than flames and boiling water. It is this period in history which many people dream about, lust after and drool over, when they think about steam-trains. But what was it like back in the 1870s, until steam-trains finally became obsolete in the 1950s?

Driving a Steam-Train

Every little boy has probably grown up, wanting to drive a steam-train. They want to pull the levers, yank on the whistle-cord, shovel the coal and ring the bells. They want to hear the “Whoooo!” of the train-whistle as it clatters along at breakneck speeds! Like the boy in the ‘Polar Express’ movie, they want to yank on the whistle-cord and yell out over the clanking of the machinery, “I’ve wanted to do that my whole life!”

But what is it actually like, having to drive one of these great big, clanking metal beasts?

Everyone has a pretty rudimentary understanding of how a steam-train works, and really, that’s all you need, because they were very simple machines…in theory, anyway. They relied on steam-pressure, heat, fuel and water. This is how they worked:

First, the boiler was filled with water. A steam-train’s boiler could take hundreds of gallons of water. Once the boiler was filled, the fire in the firebox in the cab was lit.

Early steam-trains used wood to fire their boilers, but this was eventually replaced by coal, which remained as the mainstay of steam-powered locomotives until their demise in the mid 20th century. Coal was easier to toss into the firebox and it burned much hotter than wood, which made it more efficient. Once the fire was lit inside the firebox, it was the job of the fireman to shovel as much coal as he could into the firebox to build up the blaze to a blistering, white hot heat. This heat boiled the water inside the boiler and inside the fire and steam-tubes which surrounded the firebox.

Once the boiler was full and the fire was burning white hot, the fireman and engineer had to sit back and wait for things to happen. While they tapped their feet and checked their watches, the fire continued to burn. As it burned, it boiled the water which turned to steam. When the train wasn’t moving, the excess steam was vented through special safety-valves in the train. Failure to vent the steam could result in pressure building up too much and the entire boiler exploding!

When the train was ready to go, the engineer pulled on a lever which opened the valve in the ‘steam-dome’, one of the two humps on the top of the boiler. By opening the valve in the steam-dome, he released steam from the boiler down a set of pipes towards the pistons. As the steam-pressure built up, it forced the pistons forward, and this forced the driving-rods to move forward. The driving-rods were connected to the wheels, so when the rods moved, the wheels moved as well. At the end of this half-revolution, the steam switched positions in the piston-cylinder, thanks to a set of alternating valves, which forced the steam into the main pistons in the opposite end, forcing the piston back the other way, completing the rotation of the wheel, and forcing the spent steam out of the train through the smokestack at the front. When you see smoke coming out of a steam-train, half of that smoke is probably steam as well, spent steam coming from the pistons at the end of each revolution of the wheels. The distinctive ‘chuff-chuff’ sound that is synonymous with steam-trains, is the sound produced by the pistons with each revolution of the wheels and the exhaust of the spent steam.

Getting the train going was the easy part. What wasn’t so easy was maintaining speed and safety. Steam-locomotives required constant attention. There was no cruise control, no auto-pilot, no snooze-button. You had to keep an eye on everything. It was the job of the fireman to continually shovel coal into the firebox to keep it roasting hot so that the water would never stop being superheated and ready to produce steam. It was the job of the eingeer to do almost everything else.

Being an engineer was not exactly a cushy job. You had to keep your hand on the throttle, regulating steam-pressure all the time. Not enough steam-pressure and the train would stop. Too much, and the train either sped up, or it just blew up! You had to keep an eye out for obstructions on the tracks such as other trains, cows, people, fallen trees or landslides. You had to know when to speed up and when to slow down. Speeding up was pretty easy, stopping wasn’t. Most steam-trains did not have pneumatic breaks in the 19th century. These days, brakes are worked by air or oil-pressure. Back in the 1880s, they were worked by muscle and brawn.

If a train had to stop, the fireman and the engineer would have to stop the train by hand. Literally. They grabbed the brake-lever and they pulled for all they were worth! The lever operated simple wooden or metal brakes that stopped the wheels by friction.

The basics of steam-train mechanics changed very little from the late 1800s until the end of the era in the 1950s. There were improvements on steam-pressure efficiency, locomotive-design and speed, but how an engine got moving and how it stopped remained unchanged for over 100 years.

The famous and enormous ‘Challenger’-class steam-locomotive

The photo above, is of the famous ‘Challenger’-class steam-locomotive, which was built in the 1930s and 40s. You’ll notice that it has two sets of pistons. This was to make better use of the steam provided to the pistons from the boiler. The steam entered the rear pair of pistons first, moved those, and then the exhaust steam from there was fed into the front piston-cylinders which then turned the front wheels, providing more power for the same amount of steam. It was then ejected out of the engine through the smokestack. Double sets of pistons such as these, were just one innovation that designers introduced to steam-trains to make more efficient use of the steam produced by the boiler.

The Golden Age of Steam Trains led to all kinds of companies springing up. Nearly all of them had the word ‘Pacific’ in their names. Let’s look at them, shall we?

Central Pacific Railroad.

Canadian Pacific Railroad.

Union Pacific Railroad.

Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad.

California Pacific Railroad

Missouri Pacific Railroad.

The list goes on and on and on.

But there were a few lines which didn’t have the hallowed word ‘Pacific’ in them, which made it big. One of them was the 20th Century Limited, also simply called the ‘Century Limited’, which ran from New York to Chicago on a daily express service between the two cities. The 20th Century Limited was designed to provide people with speedy, efficient service between two of America’s greatest cities, and it did just that, for over half a century, from 1902 to 1967. It is said that the term ‘Red Carpet Treatment’ came from the Century Limited, from its habit of rolling out the red carpet (literally) to their carriages on the platform, so that its passengers would know where to go!

This swanky, 1930s Art-Deco, streamlined steam locomotive was one of several which had the great honour of pulling the train known to thousands as the legendary 20th Century Limited

The Pennsylvania Railroad gave its name to the famous Pennsylvania Station and the even more famous Hotel Pennsylvania (that’s PE6-5000!) in New York City.

But few other railroad companies captured the grandeur and mystery and luxury and romance of steam-powered locomotive travel, than the famous and legendary…

Orient Express.

The Orient Express

The Orient Express. The very words conjour up thoughts of mystery, romance, escapism, the ultimate European holiday, espionage and horror! For over 100 years, since the service first started in 1883, an express train, belching steam and smoke, has always thundered across the railways of Europe, whisking people from Calais in nothern France, to Istanbul in Turkey in the east.

Over the years, there have been several lines which have called themselves the Orient Express. There have been five in total, running from 1883 to the present day. Although they were interrupted by the World Wars, which ripped Europe apart from 1914-1918 and 1939-1945, they have continued to provide romantic and stunning service to passengers who wish to recapture the glamour of riding the rails as so many of our grandparents did, back in the 20s and 30s.

Railroad Time

One aspect of steam-train travel which many of us are probably familiar with, through film and television, is the iconic scene of a blue-suited conductor standing on a platform with a gold pocket watch in his hands, calling out the words: “All aboard!”.

Railroad pocket-watches had to be incredibly accurate. Here, a conductor and an engineer synchronise their watches before their next journey

Keeping trains running on time during the golden age of railroad travel in the USA and Canada was literally a matter of life and death. Failure to keep trains running on time could result in devastating train-wrecks which could (and did) cost men their lives. To combat this, the top American watch-companies of the day produced pocket watches called railroad chronometers to keep all the trains on the track and on time. There’s no fun in having a steam-train crash into another one and sending boiling water and flaming coal all over the place! You can read more about railroad chronometer or railroad-standard pocket watches here.

Here’s my own railroad-standard pocket watch:

it’s a 1960 Swiss-made Ball railroad chronometer with a 10kt gold-filled case. Specs are:

21 jewels.

16 size.

6 Adjustments + temperature & isochronism.

Micrometric regulator.

Large, Arabic numerals.

Every minute and second clearly marked.

Lever-set, crown-wind.

Screw-on caseback & bezel.

24-hour dial (this last specification was mandatory only for Canadian railroads, on which this watch was used. It wasn’t mandatory in the USA).

Hi Shahan,

This is a lovely brief history of railroads and I have been reading a lot about railroads lately! I especially like your attention to details. So I am wondering if you have come across any specific information about how often a steam locomotive had to take on coal and water – how far could it run on a certain amount? I have heard about 200 miles between service stops, but have no more information that that. Perhaps it is extremely variable, but I thought I might ask you. Thanks for any help you can provide.

Hi Barbra,

My reading and research tells me that a steam locomotive with a tender could run for as long as the water lasted. Because so much steam was required to power the locomotive, the train was more likely to run out of water before it ran out of coal. There often water-towers or tanks at railway stations or at railyards for trains to top up. Some railways even had “track pans’, troughs between the rails where the engineer could pull on a lever in the cab. The lever lowered a chute into the track-pan and the speed of the locomotive forced the water in the pan (rainwater) up from the track into the train’s boiler.

If a locomotive was desperate for water, it would probably stop at a bridge over a river or near a lake, toss in a hose and then pump the water from river/lake directly into the boiler from there and then steam off on its way.